During this Thanksgiving season, let’s try something different: Rather than focus on doom and gloom, what hasn’t been accomplished and what irreconcilables are trying to undo, let’s focus on an improbable success story.

During this Thanksgiving season, let’s try something different: Rather than focus on doom and gloom, what hasn’t been accomplished and what irreconcilables are trying to undo, let’s focus on an improbable success story.

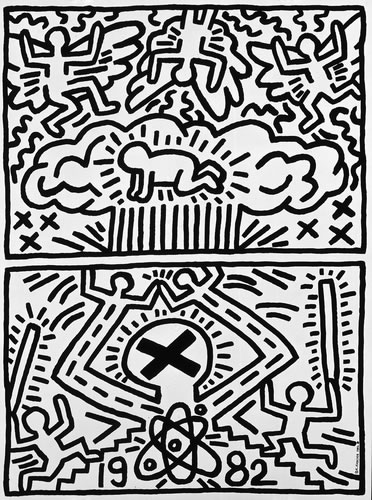

Despite the odds, prolonged efforts to cage the Bomb have been surprisingly successful for major powers. No one confidently predicted this success when the Bomb made its surprise entrance, and certainly not when early attempts at nuclear abolition quickly failed. And yet, after decades of hard work, the utility of nuclear weapons for major powers has been progressively diminished, even though they retain thousands of warheads.

Success has been achieved despite powerful constituencies that resisted progress every step of the way. Treaties banning atmospheric nuclear tests, limiting yields of underground testing, and then ending all tests with explosive yield were bitterly contested. Opponents mistakenly equated greater national security and public safety with more nuclear testing, but the reverse has proven to be true. Critics also misfired by attacking the Strategic Arms Limitation accords pursued by the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations. These efforts were strongly opposed for allowing the Soviet Union greater leverage and nuclear war-fighting advantages over the United States. Instead, the combination of diplomatic engagement and containment resulted in the Soviet Union’s dissolution from its own contradictions and dysfunction.

Next, critics challenged verifiable strategic arms reduction accords pursued by the Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Obama administrations as weakening America and shriveling extended deterrence. In actuality, alliance solidarity is challenged more by opposing treaties and their ratification. Even the administration least interested in negotiating verifiable reductions in nuclear forces did its part: Under George W. Bush, the United States reduced stockpiled weapons by huge amounts.

The incremental process of nuclear arms control and disarmament between Washington and Moscow has had staying power, despite rocky intervals. To be sure, strategic modernization programs continue. There are now and always will be difficult periods between major powers. Even so, the Bomb is not nearly as influential and useful as previous generations thought. Stockpile size and force structure for four of the P-5 have dwindled. China has yet to accept the responsibilities that come with membership in the P-5 and the Nonproliferation Treaty, but it has — so far — adopted a very different, saner nuclear force posture than the United States and Soviet Union during the Cold War or at present.

Success has been far more elusive with nuclear newcomers, who now pose the greatest threats to nuclear order. Each new member of the nuclear club believes in the utility of nuclear weapons, challenging the norms accepted with deep reluctance by earlier entrants. Newcomers increase stockpile size to shore up systemic weaknesses or to deter stronger states. They aren’t yet ready to sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. It will take many years of strenuous effort to cage the Bomb in these hard cases. The pathways for doing so are familiar, including constraints on nuclear testing, the slow accretion of nuclear risk-reduction measures, and diplomacy to ameliorate security concerns.

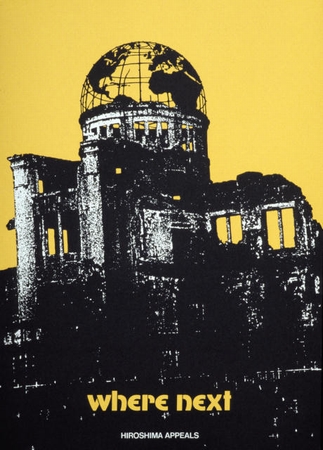

Caging the bomb in the hardest cases seems as unlikely now as during the first decades of the U.S.-Soviet competition. Nevertheless, progress is possible when unlikely combinations of national leaders permit. Norms still matter, even for outliers: Who wants to join North Korea in testing nuclear weapons and threatening to use them? Caging the Bomb in hard cases is still possible because disgrace as well as incalculable danger will result from the first battlefield use of nuclear weapons after a hiatus of almost 70 years. If, by a combination of luck, common sense, and wise leadership, the superpowers could avoid Armageddon, India and Pakistan may be able to, as well. But they aren’t working nearly hard enough to succeed.

Trend lines reflecting the Bomb’s diminishing utility for major powers have withstood the advent of new states (also less than predicted) possessing nuclear weapons. Sudden shocks to well-established norms remain entirely possible, and one of these days, we may finally be shaken from our sense of complacency against all things nuclear except for Iran. Even then, major powers will have great difficulty finding utility in weapons too powerful to test, let alone use.

Thanksgiving is, indeed, a perfect time to give thanks for the efforts of thousands of unsung heroes from the arms control agencies, State and DOD, the national Security Council, and multiple international organizations who devoted years (and in some cases decades) of their lives to making us incrementally safer, warhead by warhead.

Thanks. We need to look on the positive side more often.

This discussion presumes that “global zero” is really what all involved parties want.

I highly doubt that and that makes the discussion a bit dispensable.

Very interesting article though.

Not all arms controllers seek global zero, although many do. If one believes (incorrectly) that deterrence can keep nuclear war at bay for millennia to come, then nuclear disarmament is not urgently needed. In that case, the primary purpose of arms control would be to reduce the cost of nuclear arms, stabilize arms races, ensure nuclear stability during crisis or conventional war, reduce the odds of nuclear war, and reduce the size of catastrophe if nuclear war does occur.

If one instead believes (correctly) that nuclear deterrence cannot be relied on, even for a century, then rapid progress toward global zero is essential. All of the above arms-control goals are useful, but the primary purpose of arms control is to get as close to global zero as feasible. Lack of serious interest by the nuclear-armed nations is a major impediment to achieving this goal.

Here’s a different view:

http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-new-nukes-20141130-story.html?utm_source=AM+Nukes+Roundup&utm_campaign=db6e2dba7d-AM_Nukes_Roundup&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_547ee518ec-db6e2dba7d-236417250#page=2

MK