Just as expected, after a protracted negotiation, the U.S. and South Korea have agreed to relax the bilateral “guidelines” limiting the range and payload of South Korean missiles. It’s an election year in South Korea and — well, why mince words? The outcome makes the ruling party happy. And the more jingoistic quarters of ROK public opinion. Possibly some parts of the South Korean military. And pretty much nobody else on Earth. I’ve put my objections in electrons over at Foreign Policy.

It could have been worse, but this might not be the best showing for two years’ worth of institutionalized hand-holding of one form or another.

Media accounts of the press briefing at the Blue House agree that the cap on ballistic-missile range has been raised from 300 km to 800 km with a 500 kg payload. A “trade-off” rule allows ballistic missiles of up to just 550 km in range to carry payloads all the way up to one metric ton (1,000 kg). For UAVs, the maximum payload will rise from 500 kg to 2,500 kg, a big change that looks as if it’s meant to enable development of a UCAV. It’s not even mentioned, but in practice, no range limit has been enforced on cruise missiles, and it appears that the same understanding is in effect for UAVs.

As I say, it could have been worse. The Koreans’ opening demand for ballistic missiles was reported as 1,000 km range with 1,000 km payload. From South Korea, the difference between 800 and 1,000 km happens to be whether an object proceeding as the crow flies can reach Beijing or Tokyo. Sticking to the 800 km limit may help Seoul avoid embroilment in a multi-pronged regional missile race — provided no one notices that dropping the payload to 400 kilograms would probably bring both in range. On the other hand, Seoul may not care what its neighbors think. If Chosun Ilbo is any guide, conservative South Koreans are eager to join the “frantic arms buildup” in Northeast Asia.

Less clear is how South Korea’s security will be strengthened in the process. Just what was the point of this exercise? Even over the weekend, so many competing explanations have been deployed that you have to wonder if anybody really knows. Here’s a brief catalogue.

Rationale #1: Stopping provocations

JoongAng Ilbo, the Washington Post, and the New York Times all quoted the Blue House briefer as saying words to the effect of, “The most important purpose of the amendment of the missile pact is to deter military provocations from North Korea.”

So is the plan to send conventionally armed medium-range ballistic missiles streaking into the DPRK in response to the next shelling from the north? One wonders. The upcoming introduction of GPS-guided artillery rounds by the U.S. military seems more relevant to this problem.

Rationale #2: Nuclear Scud-hunting

But according to Yonhap, the same briefer, senior presidential secretary for foreign and security affairs Chun Yung-woo, also depicted the problem now being solved as the North Korean nuclear missile threat: “We will secure effective and various means to incapacitate North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities and safeguard the lives and safety of our people if North Korea launches armed attacks.”

That was also the line of a Pentagon spokesman quoted in the Wall Street Journal and a White House spokesman quoted by Yonhap, sans the explicit reference to nukes: “The ROK’s new missile guidelines are designed to improve their ability to deter and defend against DPRK ballistic missiles. These revisions are a prudent, proportional, and specific response to the DPRK ballistic-missile threat.” (On a Saturday night or Sunday morning, these identical messages presumably went out by email. For sheer convenience in capitulation, nothing beats a Blackberry.)

So now it seems that the idea is to zap nuclear missiles in North Korea before they launch. Mobile ones. Good luck finding them, and let’s just hope that preempting nuclear targets doesn’t start a nuclear war. If a nuclear war is already underway, then it’s possibly better than nothing, but maybe not by a whole bunch. The idea is not to have that kind of war.

Rationale #3: Covering all of North Korea

JoongAng alone seems to have captured the views of South Korea’s Ministry of National Defense, which cares most about reaching targets in North Korea from out of range of North Korean artillery or maybe short-range ballistic missiles:

Under the extended range, a missile fired from the southernmost South Korean territory, Jeju Island, can reach all of North Korea. Missile bases in the south are less vulnerable to attack from the North than bases in the center or northern areas of South Korea.

Responding to criticism that Seoul should have pressured Washington to raise the payload limit, the Ministry of National Defense said that if the missile’s range is less than 550 kilometers, they can carry heavier payloads, even up to 1,000 kilograms.

“Applying the so-called ‘trade-off’ rule, we can have missiles carrying warheads weighing up to 1,000 kilograms,” Shin Won-sik, an official at the ministry, told reporters at another briefing yesterday. “We can say that there’s no payload limit actually, because if we launch a missile from the central region of the country, all of North Korean territory is under the 550-kilometer striking range.”

Come visit scenic Jeju Island! Don’t forget to see the new missile brigade HQ.

All snark aside, this rationale raises uncomfortable questions about why a heavier payload is so important to the MND, which has otherwise emphasized precision strike against command-and-control, hardened artillery positions, and perhaps other sorts of targets. One also wonders what’s so important about 800 (or 1,000!) km range, instead of 550 km, if all of North Korea can be covered effectively from within the smaller radius.

Rationale #4: Joining the big powers

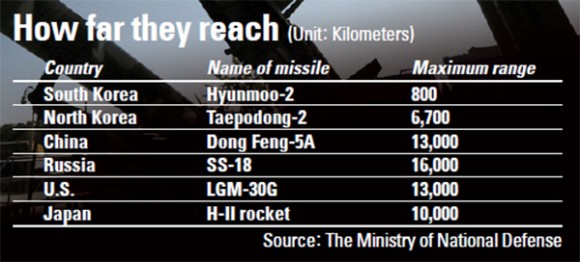

MND also has underscored to the South Korean media just how paltry a limit of 300 km seems when compared to North Korea’s iffy space launcher/candidate ICBM, Chinese, Russian, and American nuclear ICBMs, and a Japanese space launcher. Here’s what JoongAng did with their fact sheet:

In case you missed it, the same griping appeared in essay form just a couple of weeks ago in the Chosun Ilbo.

So, how would South Korea’s own Naro-1 space launcher stack up if it had been included here? Does the inclusion of the Japanese H-2 rocket indicate how the ROK MND views space-launch technology in general, surely including South Korea’s own? Does MND aspire to see South Korea join the ranks of the ICBM possessors? I’m going to assume they don’t. But if they don’t, they probably shouldn’t carry on about the unfairness of it all.

Readers are invited to vote for their favorite rationale in the comments.

Re point 4;

Better comparisons for Japan would have been with its solid-fuel space launchers (Lambda series, M-series up through M-5, the J-1).

The H-II series, with liquid hydrogen fuel, is particularly ill-suited to be an ICBM.

The “nuclear scud hunt” seems unlikely. A conventional SRBM/MRBM is not going to be effective at getting a vehicle moving down a road. It might be fast enough, if you had realtime imagery, to get a TEL if it stopped to erect the missile and fire. But if you have realtime imagery, the most likely source is a drone, and a drone with a hellfire *can* get the TEL on the road while moving…

I would (somewhat naively, I don’t study this relationship all the time) ascribe a mixture of “join the big boys” and “tit-for-tat” with North Korea; the NKs may feel emboldened if they feel they have a weapons technology SK can’t match, and SK getting parity there might stabilize.

Of course, NK has nuclear weapons, but if one restricts this to conventional conflicts between the two, that logic might hold anyways.

1 seems predicated on the assumption that the House of Kim fears ordnance delivered by ballistic missiles far more than that dropped by other delivery systems. South Korea has lots of stuff than can break other stuff.

2 is silly for reasons already mentioned. Inevitable SK air supremacy (even without the US) in any war means TELs die as soon as they’re found — the problem is finding them.

3 makes marginally more sense. Ballistic missiles can in fact hit command bunkers and artillery positions. So can aircraft, which are vastly more flexible (not to mention reusable). In any case, most of the hard targets that you would want to destroy quickly are NK artillery pieces near the DMZ, hardly justifying the range emphasis.

4 certainly seems the most plausible of the bunch. It seems a bit odd that South Korea would view MRBMs as such a status symbol, but I could see how a perception of falling behind the North in any weapons category would be unpalatable.

I’d propose another possibility. They want a long-range runway-busting option in not-so-permissive air environments, in the vein of the Second Artillery. Obviously, this is wasted on the KPAF’s MiG-17s, but could be useful against other regional powers. Or against powers outside the region, for that matter. The ROKN is building its global reach, and the fact that they’re putting 1,500 km range cruise missiles on 10,000 km range Aegis destroyers does suggest they see some utility in making stuff outside the neighborhood go boom.

Apparently, koreans are obsessed with rankings, negative and positive: By Jon Huer

Korea Times Columnist

Most foreigners are quite baffled at how single-minded Korea is in knowing exactly what ranks it holds compared with other countries. After all, the victim psychology and the desire to be great are perhaps two facets of the same framework.

It is indeed difficult to read a newspaper in Korea without finding some references to Korea’s world ranking in one area or another. Koreans are very keen on knowing how many notches they have moved up in one area and how far behind they have fallen in another. It makes their day as easily as it breaks their heart.

Naturally, nothing thrills them more than finding out that they are ranked higher than countries normally considered their competitors.

Similarly, a great collective lamentation takes place if they have fallen in one ranking or another. Korea is also keen on how many years it will take before it become number one in this, or number two in that, or number three in the other.

(src: http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/opinon/2009/09/272_39941.html)

So, they feel humiliated by the short range of their missiles.

South Koreans may be connecting the unhappy events of 2010 to the missile and nuclear tests of 2009. I’ve argued for that connection myself: http://pollack.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/3534/instability-within-stability-korea.

The problem is that the equation doesn’t work the other way around. “Catching up” to the enemy in a category of strategic offensive capabilities adds little when it comes to stopping acts of low-level aggression.

We more often notice the North’s attempts to catch up with the South: seeking a light-water reactor after the South built its first ones; landing an obscure international sports event right after the Seoul Olympics and building giant hotels and sports venues in Pyongyang to go with; and most of all, striving to make its economy and technology base look halfway as strong as South Korea’s. How strange to see the opposite.

The more I think about this, the more it seems targeted at other regional actors. A MRBM gives S. Korea more options if the inter Korean conflict is used as leverage in a dispute with China.

I’ll be interested in watching how Japan reacts in the short term.

With the publicized development of a cruise missile of the 1000km class range, Seoul will have the ability to strike anywhere in the North and probably to do some SCUD hunt provided they coordinate their strikes with US intel. BM are just overkill if you ask me.

So the only plausible solution to your question is that they want to be able to do it.

By the way, if there is range/payload tradeoff possibility as you say I think the Chinese/Japanese argument becomes void.

From what I can tell, this does look likely to impact very badly the MTCR treaty, especially as it appears that the US didn’t bother notifying it’s partners in the agreement.

Many nations are likely to be very interested in sophisticated ballistic & cruise missiles with greater range – why shouldn’t Russia or China export/aid in their development now?

Some of the reactions I’ve read so far:

“…Arms-control advocates say a U.S. decision to help South Korea boost its missile range beyond the MTCR limits would undermine the pact and open the flood gates to missile proliferation, notably by others who may feel less constrained.

“Agreeing for any country to develop 800-km range missiles, well outside the MTCR limits, would be a big mistake,” said Thielmann, now of the private Arms Control Association in Washington….

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/06/us-usa-korea-missiles-idUSBRE89502Q20121006

—

Daryl G. Kimball, the executive director of the Arms Control Association, expressed worries over adverse effects.

http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2012/10/08/56/0200000000AEN20121008001200315F.HTML

—-

I’d also be interested in seeing if it has any effect on the INF treaty. If the US just rips up treaties anytime it decides to without even bothering to consult it’s supposed partners in such agreements, as with the ABM & now the MTCR treaty, why should the Russians not just declare the treaty’s been made null & void?

An extended range Iskander system would allow them to target the ABM infrastructure in Europe without the headache of having to deploy them in Kalingrad.

I’m seeing very little reason that the US has left for the Russians not to go ahead with something like that, or to start developing something like an extended range Brahmos for India, etc.

Just for clarity’s sake, since there seems to be some confusion, the MTCR isn’t a treaty. It’s a suppliers’ cartel. Background information and the text of the MTCR guidelines can be found here:

http://www.mtcr.info/english/index.html

As Jeffrey ably explained in his FP.com essay, the ROK missile guidelines are older than the MTCR and distinct from it.

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/10/09/missiles_away

Not only is the MTCR a voluntary cartel/restraint agreement, it is also not related to countries producing their own indigenous missiles. In other words, the MTCR does not prohibit South Korea from producing its own missiles of whatever range. Just like MTCR member Turkey announced earlier this year it wants to develop 2500km range ballistic missiles. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-aims-to-increase-ballistic-missile-ranges.aspx?pageID=238&nID=12731&NewsCatID=345. Furthermore, the MTCR does ‘allow’ transfers of MTCR missiles under certain conditions, even though such transfers are sometimes controversial. The USA has supplied tomahawks to the UK, European MBDA has supplied Storm Shadows to Saudi Arabia and the UAE and has offered the 500km range Taurus cruise missile possibly to South Korea.

( http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/south-korea-to-invite-bids-for-f-15k-cruise-missile-356969/ )

The USA has in the past been involved in South Korean ballistic missile production, when the first South Korean ballistic missiles with a range of 150km or so were based on obsolete US supplied Nike hercules missiles. As a result at that time it was particularly easy for the US to demand range and payload ceilings from the Korea. That seems to be more difficult now when the technology appears to come from elsewhere and US demands presumably are coupled to US military support for South Korea in general.

The latest longer range South Korean missiles, the Hyunmoo-2 ballistic missile of 300km and Hyunmoo-3 cruise missile of 1000 km range, appear to be based largely (?) on non-US technology. An explanatory video can be watched at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LBu02s3Fpc0&feature=related

The video also highlights a possible explanation for the interest in a 1000kg payload. The bigger the payload, the higher the number of submunitions or the bigger the explosive aimed at destroying North Korean bunkers.

For the Hyunmoo-2 it has been suggested that it looks like the Russian Iskander and may include Russian technology, the H-3 appears to be mainly based on South Korean technology. For sure any MTCR member state that supplies key technology for the Hyunmoo-3C would have to ensure that this is one of the MTCR’s ‘rare occasions (…) where the Government (A) obtains binding government-to-government undertakings embodying the assurances from the recipient government called for in paragraph 5 of these Guidelines and (B) assumes responsibility for taking all steps necessary to ensure that the item is put only to its stated end-use.’

So… (now done with conference I was at earlier in the week)

Taking the step back, a large chunk of this seems to simply not match the South Korean’s direct military threat/response map (North Korea). They wanted complete coverage for that; they got it, and enough more that they’re edging into holding Tokyo (highly unlikely, but SK may historically not see it that way) and Beijing (unlikely, but more credible than Tokyo) at risk.

The value of such, with conventional warheads, seems generally somewhat suspect. However, the conventional warhead SRBM/MRBM/IRBM/ICBM seems to be catching on, and for some hard targets it might be a good match. The question of what SK would want to precisely attack in Beijing, as opposed to hold the city at risk for light dispersed area bombardment, seems questionable (a strike on nuclear-armed, very-geographically-dispersed China’s command and control facilities?? I hope that’s not on the SK security agenda…).

The other alternative I can see is that they actually primarily want heavier throw weights and deep penetrators for North Korea targets, along with hold-all-of-NK-at-risk range from southern SK, and that nominal ranges edging up into Tokyo/Beijing were incidental (or, primarily incidental, and a mildly politically useful posturing stick other than that).

It might be worth modeling up what bigger penetrators on hypothetical next-gen SK SLBM/MRBM missiles might look like.

Honestly, I can’t really imagine the South Koreans wanting to attack Japan. China, maybe, but more as a deterrent than anything else; they certainly can’t have any strategic illusions WRT what the results of an aggressive move in that direction would be. If they pick a fight with China it will be a trade war. Same with Japan but even less likely, is my take.

OTOH, a very robust retaliation capability against the North Koreans seems consistent with the attitudes of the South Koreans I’ve interacted with. I expect that’s what they have in mind.

Now, how other actors (including afore-mentioned China and Japan) might make of it, that’s a different question. And I too will be interested to see how they react.

In recent (last 75 years) history, all of North Korea, China, and Japan have invaded South Korea. China only allied with NK, not independently, but they certainly participated. Japan invaded and occupied in WW2.

They also undoubtedly see Russia as somewhat of a risk, though there’s no direct history. Russian pilots and munitions in the Korean War, but no direct intervention.

Under current geopolitics, it’s unlikely they’ll need to go on either the offensive with or seriously deter any of the above other than North Korea. But I can imagine that their military planning cases still include “What if Japan comes after us again?”, and all the others. NK being their major threat doesn’t mean the others that were within people’s lifetimes go away entirely.

It appears to me that South Korea is growing increasingly interested in being able to strike a large number of the hardened targets in North Korea without substantial US assistance. I don’t find that too puzzling.

Also, many important targets in the northern part of the North Korea may be within the engagement ranges of sophisticated PRC SAMs.

To George Herbert: you write about targeting TELs moving down the road, and the poor suitability of BMs for this mission. I haven’t seen much in the open about DPRK mobile missile doctrine. I can’t find any pictures of their TELs on the roads except in parade (as you can for PRC). Is there reason to think DPRK’s doctrine for mobile missiles — for conventional or NW-armed mobile missiles — involves significant overland movement between hiding spots? The alternative is that the TELs are in underground bunkers, perhaps each with a couple exits. The latter DPRK doctrine, if the US and ROK have been staring at it for decades, might produce a few hundred very high priority hardened targets.

I am not saying I know the answer on the mission for the ROK BMs. But we might be understating their counter force role BC we’re mischaracterizing DPRK’s mobile missile doctrine.

Actually, ballistic missiles might be very useful against mobile TELs. In particular with submunition warheads, like in the case of the South Korean Hyunmoo-2. Once a TEL has been detected a BM will reach it faster than a cruise missile or combat aircraft, i.e. has a higher chance of hitting the TEL before it has moved on. Isn’t that what the US prompt global strike conventional armed ICBM idea is also about.

A submunition warhead will compensate for the BM being less accurate than cruise missiles or aircraft launched guided munitions (which South Korea by the way receives in significant numbers from the USA as part of their efforts to build up a capacity to destroy all kinds of strategic targets in North Korea). An armed UAV could do the job too, but South Korea does not have such UAVs yet. They do have however have recce UAVs, want to buy high altitude UAVs and other ISR tools that cannot destroy targets themselves.

So rationale 2, the kind of war Jeffrey does not want to have for good reasons, seems plausible enough as pretty significant one.

For a more graphic explanation of the utility of a BM against soft targets and a cruise missile against a hardened target watch the video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LBu02s3Fpc0&feature=related

I have the same basic basing assumption, that they live mostly in deep rock.

The problem going after that with missiles is cost. Missiles are far more expensive than deep rock bunkers. Even with the relative economic advantage, NK could dig more bunkers into mountains than SK could kill that way, which leads back to realtime movement intel – at least, more realtime than the missiles move around.

You can see silos; TELs are hard.

I agree that one cannot expend missiles on each tunnel entrance — the ROK would need some means of identifying the most likely ones. We can imagine a range of ways that they could try to gather that information.

Conventionally armed ballistic missiles may be only one part of the ROK effort against mobile missiles and the bunkers they inhabit.

I think the ROK government / military is thinking hard about what they will do if deterrence fails in the Peninsula (ie, conventional war of some sort), and they think the odds are non-trivial that in that circumstance NK will use WMD, leaving the ROK with the need to limit the damage as effectively as possible. I know it’s verboten to talk about “if deterrence fails” among some on this list (not you), but I suspect that the ROK conventional missiles have a role in that mission (damage limitation if war erupts on the Peninsula).

If we try to figure out what the post-2010 ROK “pro-active deterrence” concept articulated and pushed hard by former Blue House national security advisor Kim Tae-hyo actually means, we end up with a propensity to fire-first, ask-questions-later (at least as far as rules-of-engagement along the western offshore front are concerned); plus sledgehammers aka the missiles that were announced along with cruise and UAV range and payloads.

This “we are in big boy league now” strategic concept is spelled out clearly by Kim Tae-woo, ex-KIDA, now head of KINU. See for example, his The need for strategic weapons capable of striking anywhere in North Korea “New Missile Guidelines” must be revised, Korean Institute of National Unification (18 May 2012), at:

http://www.kinu.or.kr/eng/pub/pub_05_01.jsp?bid=EINGINSIGN&page=1&num=99&mode=view&category

The flavor of “pro-active deterrence” is stated up front in Kim’s analysis: “A “triad system” represents deployment of deterrent weapons (ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, unmanned aircraft, etc.) in the air, under the sea and on the ground. As for the platforms such weapons will be mounted on, we should prioritize the purchase of the 5th-generation combat planes and KSS-III class submarines. For deployment on the ground, we need to develop mobile launchers and expand and refurbish the existing Guided Missile Command…”

Background on the deeper political-bureaucratic origins of the concept of pro-active deterrence can be found in Rhee Sang-Woo’s From Defense to Deterrence: The Core of Defense Reform Plan 307, CSIS, September 7, 2011 http://csis.org/files/publication/110907_FromDefensetoDeterrence_Rhee.pdf

The problem, as USFK and MND officials will attest, is no-one knows how this concept translates into operational practice and warplans in order to manage crises and avoid escalation before, during, or after low level overt and covert conventional attacks from the DPRK.

For the resulting dilemmas that arise from this concept, the best analysis in public domain is Abraham Denmark’s Dec 2011 excellent Proactive Deterrence: The Challenge of Escalation Control on the Korean Peninsula, at:

http://www.keia.org/sites/default/files/publications/proactive_deterrence_paper.pdf

As he states: “The possibility of preemption by the ROK by what it assesses to be an imminent small-scale attack from the North is espe¬cially problematic from an escalatory standpoint. Although it is unclear that preemption is an explicit element of Seoul’s proactive deterrence approach, the statement by presidential spokesman Lee Dong-kwan that the principle of proactive de¬terrence is “to preempt further provocations and threats from the North against the South, as well as simply exercising the right of self-defense” certainly suggests as much. The danger of preemption is the potential that Pyongyang may respond with an attack more devastating and shocking than what may have been originally intended, especially if domestic North Korean politics come into play and Pyongyang sees itself as unable to back down.”

Might I offer some suggestions:

1) Having guided missiles pre-targetted at fixed North Korea command and control facilities would free up those fancy F-15s, F-16s, F/A-50s and later KFXs to go hunting for tactical targets along the border, artillery pieces and the like. Whilst it is true that an F-15 can fly a long way it can also carry a large number of PGMs a shorter distance and combined with its array of optical sensors and the AESA it will inevitably be fitted with it will make for a lovely AFV/SPG hunter. MRBMs would relieve it from its time consuming deep strike mission.

2) it is fairly obvious looking at large parts of South Koreas arsenal that in addition to pinning North Korea it is also engaged in the regional great game squabbling as it does with the Japanese and the Chinese in equal measure whilst distrusting both. Keeping up with the neighbours is imperative- the entire US apac pivot suggests that there is potential for some form of conflagration

3) And also related to the above, one of the great turning points of the Korean war was China’s entrance, one suspects that the South has not forgotten this. We tend to see South Korea and north Korea through a western prism of rogue states when in reality the whole region is in an arms race, North Korea is just one of many issues, it is unclear what China’s position is on it and the lesson f the first Korean war is that not everybody might be so convinced that the North should lose.

Hard targets or not, there doesn’t seem to be any *smart* reason to have extended the range as far as they did, let alone as far as they wanted. I can’t see any combination of outcomes, no matter how arcane, for this to make a great deal of sense in a purely rational way.

So I fall back to my default position: the problem is people. The cringingly awful wording that gave an aim of, huh, “deterring provocations” (puke) makes utterly no sense militarily, but it’s the sort of thing that’d play well to not-thinking-about-it-too-much elements of the public and even the political class. So I’m going to wave my hands in the air and say “domestic politics”. That tends to make me look pretty smart, no matter how ignorant I am (which in this case is: almost entirely).

But that still leaves the US, and what the hell their people were thinking. I just cannot see how anything here is in their interests. What bizarre sequence of wished-for events could even a career realpolitik imagineer have squirreled away in those hardened, deep-rock silos in their heads that ends in a good result for the US? There’s no real tension to relieve between them and South. There’s no significant immediate advantage. The direct reason isn’t there. So what’s the convoluted domino chain that is supposed to happen now? And what falls over at the end?

Not suggesting for a moment that the plan is actually going to work, or is realistic in any way. Just trying to work out what people *thought* they were doing…

Perhaps they’re thinking of something like Assault Breaker? Someone mentioned submunitions upthread. They have a need to stop a wedge of Soviet armour, the original requirement for it, but perhaps more importantly, to engage a lot of artillery targets quickly and ideally from outside the artillery engagement zone.

The Viper Strike is apparently 20kg, for this requirement I think more might be needed, but a ton of payload would give you ten-ish SDB-class warheads in a sort of “mini-MIRV”. And although you could get more range by reducing the payload, if it wasn’t range you were after you might be able to up the payload.

The tell would be what they’re doing in terms of ISTAR systems to cue it. Assault Breaker led to both JSTARS and the RAF’s ASTOR. Perhaps putting a fancy radar on a UAV, or buying something like ASTOR?