Pakistan is blocking the start of negotiations of a global halt to the production of highly-enriched Uranium and Plutonium for nuclear weapons. The Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty can’t begin, Pakistani diplomats say, because existing stockpiles won’t be covered. But Pakistan would be loath to reveal its existing stocks, and no one in any position of authority would permit foreign inspectors to verify their locations and extent. And if, by some miraculous event, existing stocks were covered in the treaty, an absolutely necessary first step would be to verify a freeze on existing production – the very agreement that Pakistan wholeheartedly resists.

Another problem with an FMCT, Pakistani officials say, is the civil nuclear deal offered to India by the United States. This deal, they assert, will allow Indian authorities many new sources of fissile material to make bombs. But foreign companies aren’t rushing into the Indian nuclear power market. Instead, they are keeping their distance because of meager liability protections passed by the Indian Parliament. Even if, in the future, Indian liability laws are changed and foreign companies build dozens of new power plants, the diversion of electricity into bombs is very unlikely. India has facilities dedicated to military production, and no longer needs to poach on power plants to make weapons.

A related Pakistani argument used to block the start-up of FMCT negotiations is that India’s breeder reactor program will provide an open-ended source of fissile material for weapons. This presumes that India’s breeder program, unlike that of the United States, Great Britain, Germany, France, Japan and Russia, will actually prove to be worth its considerable investment. Even if New Delhi continues to subsidize the breeder program, there will be severe domestic political penalties for diverting electricity into bombs. Pakistani analysts who warn of this outcome are projecting their own civil-military relations onto India.

Pakistani officials have suggested that they will lift their veto on FMCT negotiations if they are offered a similar civil nuclear deal to the one granted India. This argument undercuts all others against the FMCT: if status trumps security, then the security-related arguments against the FMCT can’t be very serious. Besides, calling for a similar civil-nuclear deal is wishful thinking. Pakistan can’t afford nuclear power plants unless they are offered at concessionary rates, as China has done. Everyone else will invest only with profit in mind, and Pakistan now figures to be a very risky place for large investments. Foreign investment can become more attractive with greater domestic tranquility, sustained economic growth and normal ties with neighbors, but even then, nuclear power will not be an attractive sector for investment. If Pakistan’s stand on the FMCT is about foreign investment, status and pique about India’s civil nuclear deal, blocking the FMCT negotiations is an especially unwise strategy, since it confirms Pakistan’s diplomatic isolation.

Another argument against the FMCT is that Pakistan can better resist outside pressures – especially Indian adventurism – by having more nuclear weapons. But Pakistan’s susceptibility to pressure comes from its domestic and economic weaknesses, not from the number of nuclear weapons it possesses. For the last two decades, Indian governments have concluded that sustained economic growth is more important than fighting with Pakistan. Attempts to seize and hold Pakistani territory would result in severe trials. Pakistan’s nuclear inventory has also helped dissuade Indian leaders from engaging in military adventurism. If this has been the case when Pakistan possessed fewer weapons, why would a larger inventory be required — especially if an FMCT would constrain a parallel Indian build-up? Besides, the threat of an Indian conventional offensive would only be prompted by spectacular attacks on Indian soil carried out by individuals trained and based in Pakistan. Preventing the groups that engage in these tactics would also prevent unwanted Indian military responses.

Yet another argument against the FMCT is that nuclear weapons are not that big a drain on the Pakistani treasury. But Pakistan has so many unmet needs that any opportunity to meet some of them would appear to be worthwhile. The clinching argument against the FMCT in Pakistan is that it is a thinly disguised attempt by outsiders to take away Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent. In actuality, Pakistan’s current position on the FMCT, calling for the inclusion of existing stockpiles, would pose a greater threat to Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent than the negotiating mandate Pakistan is resisting, which would leave current stocks untouched.

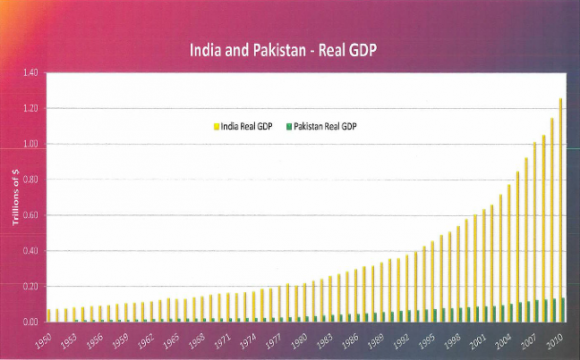

With or without the FMCT, Pakistan will retain nuclear weapons. So, too, will India. Pakistan can compete with India to increase its nuclear stockpile. But the country with a weak economy loses this competition.

Pakistani arguments against the FMCT are weak. The primary reason for Pakistan’s nuclear build-up is instinctual rather than analytical: India is forging ahead while Pakistan is in a downward spiral. The great disparity in Indian and Pakistani economic fortunes clarifies why Pakistan’s military leadership continues to increase its nuclear stockpile – and why this means of compensation further diminishes Pakistan’s prospects.

A slightly different version of this essay was published in Dawn, an estimable Pakistani newspaper. Shortly afterwards, a colleague from Pakistan e-mailed a rebuttal, which he has permitted me to reproduce below. I am posting his unabridged response in the hope that it will stimulate further analysis and discussion.

Reference our e-mail exchange regarding your article on FMCT. Following are my thoughts:

1. You have selectively referred to our position on FMCT without dealing with the whole picture. This needs to be exposed by presenting the comprehensive argument regarding our position on FMCT. Essentially it is not driven by status and pique but by our legitimate security concerns which require full spectrum deterrence as long as discrimination against Pakistan continues in the strategic arena.

2. If the negotiations were about a Fissile Material Treaty and not just FMCT Pakistan would be willing to accept reduction of stocks and verified freeze on existing production as this would apply to all nuclear weapon states including India as a result of which Pakistan would not be at a disadvantage. But a freeze on production without reduction of stocks will put Pakistan at a disadvantage vis-a-vis India.

3. The danger of the civil nuclear deals offered to India is not because American companies are not rushing into the Indian nuclear power market but because the deal not only rewards India for its proliferation activities but provides India with the potential to use fissile material from these deals for civilian uses and its indigenous stocks exclusively for weapons purposes. Even worse India can divert this imported nuclear material for its weapons use because the monitoring arrangements involved are insufficient to prevent this. Besides, while US companies may not have concluded any deals with India, French and Russian companies have already done so and these deals are without any effective controls on the end use of the fissile material in India.

4. The argument that India will not divert fissile material from civilian to military use as it no longer needs to poach on power plants to make weapons is unsustainable because if this was the case then India would have agreed to the tighter monitoring controls that were being insisted upon by some NSG members before it was given a waiver. Moreover, India’s track record of cheating is already well known (You should know this as you have written an article criticizing the absence of effective monitoring controls in the NSG arrangements for India.)

5. India’s fast breeder reactor programme may not be working efficiently at this stage but we cannot make our security decisions on the basis of anticipated Indian inefficiency. India’s fast breeder reactors as well as its growing stocks of reactor grade Plutonium which can be used in crude nuclear bombs needs to be taken into account by Pakistan.

6. Pakistan’s demand to be treated at par with India is not driven by the search for equal status but by security considerations. Civilian nuclear agreements as permitted for India will enable Pakistan to develop its civilian nuclear capabilities for power generation needed to meet its energy requirements. At the same time, Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities would be then more capable of focusing on ensuring our deterrence requirements. This approach also does not undercut Pakistan’s stance on a fissile material treaty because Pakistan, like India would be at par in terms of acquiring civilian nuclear cooperation for power generation and ability to then focus indigenous resources on upgrading its nuclear deterrence till an FMT is concluded.

7. As regards the alleged diplomatic isolation, for Pakistan it is far more important to guarantee its security than be concerned about diplomatic isolation. Moreover, Pakistan is not isolated on this issue in the CD or in the UN as a large number of countries belonging to the Non Aligned Movement recognize that FMCT negotiations must take into account the security concerns of states – in this case Pakistan – and that it is due to political considerations that the FMCT negotiations have made no progress.

8. Pakistan does face economic challenges which incidentally are largely due to the role it has played in helping the US in the war on terror which has cost Pakistan over 40 billion dollars over the last ten years apart from indirect costs which are even higher. Due to these economic constraints, Pakistan’s security has come to rely on strategic and tactical nuclear weapons especially given India’s advantage in terms of both conventional and strategic capabilities – which are being further enhanced through American, Russian, French and other sources.

9. It is also true that Pakistan has many unmet needs but it must also be recognized that the highest need for Pakistan as for any other country is to guarantee its security and territorial integrity.

10. Besides, without ensuring its own security, Pakistan’s economic future cannot be guaranteed because it is only when a country is secure and can focus on promoting its economic fortunes.

11. The argument that inclusion of existing stocks would pose a greater threat to Pakistan’s deterrence capability ignores a obvious reality that there is an asymmetry in the stockpiles of fissile material between India and Pakistan despite American propaganda claims to the contrary. Therefore an FMCT without reduction of stocks would freeze asymmetry between India and Pakistan.

Oh Pakistan!

You shall never feel secure as long as India lives!!

So, you will never be able to focus on promoting economic fortunes!!!

Pakistan’s fissile material and weapons stockpiles are larger than India’s. What parity does Pakistan want? Does Pakistan not want that asymmetry to freeze? But why talk of asymmetry wityh India alone? Why not with others too?

“Pakistan does face economic challenges which incidentally are largely due to the role it has played in helping the US in the war on terror” This is the funniest statement I have ever read in FMCT subject line. ROTFL.

I don’t buy the argument that Pakistan would be satisfied with parity with Indian stockpiles. I think Pakistan truly believes it will have to use its nuclear weapons one day. Their implied doctrine of nuclear weapon use in the face of even a limited conventional defeat on Pakistani territory betrays such a belief. If the chief aim of their nuclear stockpile was MAD, they wouldn’t be so dissatisfied with the current number of weapons they have that could wipe out 100 million people in an hour. Let’s recognize reality: Pakistan sees their nukes as usable in a conventional war and not just as a last resort. In that scenario, they must be constantly building more weapons.

Michael, thanks for writing on this important topic. I want to add a few additional points.

First, I think Pakistan’s claim that the civil nuclear deal will allow India to produce more fissile material is based not on the risk that India would divert imported uranium for weapons production, but rather on the fear that it would free up India’s domestic uranium for expanded weapons production. This was a criticism by NGOs in 2005, when the deal was announced. The main rebuttal was that India did not seem to be pursuing a large or rapid expansion of its nuclear arsenal, but was satisfied with a slower approach. So far there’s no sign of ramped up plutonium production in India, but it’s probably too early to tell since India has not yet been able to displace much of the demand on its domestic uranium.

An additional rebuttal, directed to Pakistan, would be that an FMCT is precisely the treaty that would prevent this from happening. Under an FMCT, India would not be able to take advantage of the ability to use either domestic or imported uranium for weapons production. So if Pakistan is concerned about the potential disadvantage caused by the nuclear deal with India, FMCT would be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

The same rebuttal applies to Pakistan’s concern about India’s Pakistan also cites India’s breeder program. Currently excluded from IAEA safeguards, the breeder program would have to come under international verification under an FMCT. This would prohibit India from using its breeder program to produce plutonium for weapons.

Pakistan says a Fissile Material Treaty (FMT) would have to address existing stocks, where it claims to be at a significant disadvantage compared to India. Most published estimates show Pakistan with a comparable military stockpile of fissile material to India’s. But these estimates do not include India’s stockpile of separated civil plutonium, unknown but estimated at several tons – enough for several hundred warheads. According to India’s three-stage nuclear power program, this plutonium (from the first stage) is intended to feed breeders (the second stage) and eventually thorium-fueled reactors (the third stage). In this scenario, all this civil plutonium would eventually be caught up in international verification through the breeder program.

Pakistan may not trust these rebuttals. It may not believe that FMCT would would cover these materials, would be effectively verified, or would prevent India from breaking out and using accumulated fissile material stocks to rapidly expand its military stockpile.

But I suspect the real reason Pakistan opposes FMCT is much simpler: Pakistan has made a major investment in expanding its plutonium infrastructure and wants to produce more plutonium. The rest is a smokescreen. Pakistan is no more interested in FMT than FMCT, but understands that others will oppose covering stocks, so there is little risk that a treaty would be negotiated and Pakistan would no longer be held responsible for the deadlock in Geneva.

This last paragraph cuts, I believe, right to the heart of the issue. Pakistan opposes a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty because it wants to produce more Fissile Material.

A missing angle is that China is not pressuring Pakistan to sign on (or actively supporting its position) because it wants to preserve its own option to get more Pu in response to our misguided missile “defense” program.

I think we need to separate arguments against the US-India nuclear deal, which was rightly opposed by many in the disarmament movement because it does indeed free up domestic Indian uranium for weapons use, no matter the safeguards applied to imported uranium, and Pakistani opposition to the FMCT.

A number of attempts have been made to get around the opposition to the FMCT, or at least to ensure that this is no longer an obstacle to progress with the disarmament agenda within the CD, whose value as a negotiating forum has essentially been wrecked.

The bottom line is that opposition to disarmament progress by ANY single government – Pakistan, India, or the US – should not be allowed to stymie progress by the rest of the world.

John Hallam

so what is the way forward. will the treaty be held ransome

because of one country.

What a “Reductio ad Absurdum”!

What is enough for Pakistan and India to “feel secure”? 1000 nuclear weapons? 10,000? 30,000?

It was only a short time ago when the US and USSR had played the same game with 30,000+ weapons each…Absurdity aside, US could afford it, USSR went bust.

Neither India or Pakistan can afford such an arms race at the cost of an inferior standard of living (eating grass but have their bombs), but hey, their Oxford and Harvard educated elites can play the same games as the big boys…the masses don’t count.

What a shame…

The US is out to get pakistan, overtly or covertly and does not respect its sovereign borders.

That is why it did the nuclear deal with India , to weaken Pakistan. And it will stab it in the back whenever it gets the chance.

Better for Pakistan to be paranoid. 🙂

In my opinion pakistan has more investment in fissile material production than electricity compared to india which is heading the opposite way, so it would make sense for them to oppose it.

@KREPON — would be nice to hear the indian argument to FMCT.

asim,

nobody except taliban are out to get pakistan.