Click on the image for a larger version

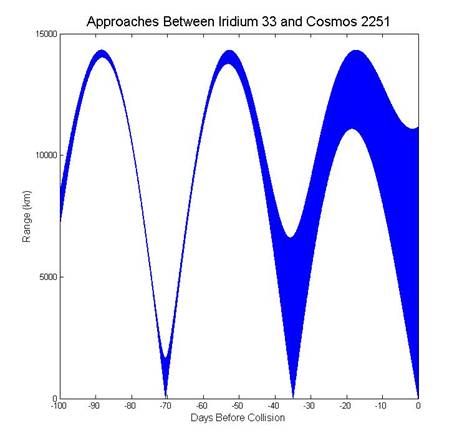

Just how much warning do you need? If a strange satellite came within 10 km of your satellite every month, would you start to worry? Apparently not, not that is, if you are Iridium. I have been puzzling over the probability of one satellite, even if it’s from the larger population of dead satellites, hitting another. I just don’t believe in such long-shot outliers (it must be something like 10,000 times less likely than space junk hitting a satellite if it was simply a matter of random chance) and figured something else was going on, even given the increased density of stuff near the poles. It turns out that there was: these two satellites shared nearly the same altitude range (as defined by their apogees and perigees) for about six years. Every 35 days or so they came within 10 km or each, which is apparently the error associated with determining close approaches. (I have a pretty cool graph that shows this by looking at the debris generated by this collision.)

Something happened to Cosmos 2251 between 1999 and 2003: its orbit unaccountably shifted down to Iridium’s orbit. Perhaps there was a leak of remaining fuel. Perhaps it was hit by another piece of debris. There is no way for me to know what happened. But once it did, the fate of these two satellites seems fixed as the cosmic clockwork of Newtonian physics ground on. (Was Russia irresponsible in leaving unused fuel on board? That might change my feeling that this was clearly an example of Iridium irresponsibly not being aware of these conjunctions.)

What can be done about this? I’m still working on that but to me its starting to make sense, as the desirable orbital altitudes start to fill up, to de-orbit dying satellites. I estimate that this will result in an increase in launch costs (unfortunately, not the only cost associated with putting additional fuel on board) of only about $1 million for satellites launched using Western launch services and half that for satellites launched by non-Western services.

Update: Unfortunately, the interpretation of these graphs (especially the one at the top of the post) is less straight forward than I had hoped. In order to lessening that confusion, I’ve added a new image that should help explain what is going on. If not, I also wrote a comment that might help some more.

De-orbiting isn’t the brightest idea. When satellites would be believed to be safe, because people are supposed to de-orbit theirs own satellites, a single accident could cause harsh problems.

Some protection might be better than killing the satellite. Space weapons, and lasers for de-orbiting the space junk might be necessary.

Greetings Geoff.

Another set of naive questions just popped in my mind for you and for whoever knows this:

What about Satellite insurance policy. Was the Iridium satellite insured? Is there a Lloyd’s equivalent for satellites? Because if there was/is there would be good money involved for people like you and others posting here (you know, calculating the odds n’ stuff). If there is a sattelite insurance thing, could we find out if the insurance fees went up after the accident and how much?

Sorry for the flow of questions but I was intrigued and I’d like to learn. Also could you inform us about liability issues. I don’t think there’s any Treaty or regulation with relevant provisions.

Wouldn’t it be fair, in this case for instance, that the Russians pay, since they haven’t designed their satellite so as to fall out of orbit after it became obsolete? Or for creating space debris, like the orbiting toolcase. Who pays if the toolcase hits and smashes something operational. I think you have written stuff on this issue in another posting.

Thanks for the patience and for the good job you are doing at the ACW.

> Something happened to Cosmos 2251 between 1999 and 2003: its orbit unaccountably shifted down to Iridium’s orbit. Perhaps there was a leak of remaining fuel.

AFAIK (someone tell me if I’m wrong) Cosmos 2251 didn’t have a propulsion system. Maybe it was a battery explosion, rupture of a pressurized compartment, etc.

Liability for damage caused to objects in space depends on who is at fault. (As opposed to damage caused to people or property on Earth or aircraft in the Earth’s atmosphere where the “launching State” has absolute liability.) This is established in the Article III of the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects:

This is why I have emphasized responsibility in my posts. Was Iridium acting responsibly when it did not take evasive maneuvers to avoid colliding with Cosmos 2251? Considering the number of times these two objects approached very close to each other, I do not think it was. Russia, on the other hand, was following the established tradition of abandoning its dead satellite in orbit. Is that responsible? According to common usage as it is currently interpreted, it probably is considered as acting responsibly. However, I think that with an increased understanding of the dangers satellites now face in an increasingly populated environment we should work toward changing what is acceptable behavior for responsible space faring nations.

As of right now, I believe satellite insurance covers mainly launch failures. Frankly, I’m not terribly concerned about which party is responsible for the destruction of Iridium 33. I’m much more concerned about preventing the creation of thousands of more pieces of space debris that could damage other satellites.

Thanks for these graphs. However, what is the source of the data? Historical ephemeris? It’s not like ACW to post charts w/o explaining them.

Also… would it be easy to post the headline chart with a log scale on the Y-axis so we could see the close approaches up close?

The data for these graphs comes from the historical two line orbital elements for both satellites.

Thanks for your immediate response Geoff.

So, you are telling me that to your knowledge no insurance covers these accidents caused by space debris or a potential collision in space like the one we are dicussing. Well, maybe they should start thinking about it, because obviously it’s an issue.

There. A new field of business and services. It will be so wonkily specialized.

Thanks again Geoff.

spaceweather is reporting some amateurs are photographing 33 and believe that much of it may remain intact based on the reflectivity.

A 10 km uncertainty for a 3 m satellite corresponds to mean time to collision of 10^7 “close approaches”, or a million years. That is a negligible risk for a satellite with an expected operational lifetime of, at most, a few decades.

Of course, there are a great many potentially colliding objects, many too many to track and maneuver to avoid. If the orbital uncertainty were reduced to 10 m maneuvers would be rarely required and collision-avoidance would be possible. To do this for many thousands of potentially hazardous objects (mostly too small to track with present systems) would be a formidable task.

While operating my radio amateur satellite earth station K3XS, I came to know the fine work done by T.S. Kelso at the Center for Space Standards & Innovation through his CelesTrak service, compiling and distributing satellite Keplerian orbital elements (also known as “two-line elements” or TLEs, after the standard NORAD data format).

I was interested to discover that Dr. Kelso also operates a collision prediction service…I’m sorry, I mean of course reporting expected “conjunctions on orbit”. 🙂

It’s called “SOCRATES” ( http://www.celestrak.com/SOCRATES/ ) for “Satellite Orbital Conjunction Reports Assessing Threatening Encounters in Space”

Don’t know if it’s been mentioned here before, but a quick Google suggests perhaps not.

I think Jonathan Katz has just proved that Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251 never collided. Must be my sat-phone that’s not working.

As for taking the blame off Iridium, don’t. Can’t find the link ATM, but they pretty clearly embraced the Big Sky Theory and rolled the dice for cost reasons.

Geoff,

For those of us who are not so well-versed in these issues, can you explain the variable vertical thickness of the line in the plot? And perhaps on a related note, what exactly does the y-axis represent? Closest pass in a given day? Something else?

Kelso’s SOCRATES service is good, but it only uses the public TLEs which are not accurate enough for collision prediction and avoidance.

Josh,

The plot at the top of the post is just the distance between Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33 as a function of time as measured every second. During most of the time, the two satellites are “out of phase,” say when the Cosmos is near the North Pole, the Iridium is near the South pole. That particular example is represented by the peaks, when the range is near 14000 km, the width at that point represents the two satellites staying on opposite sides of the Earth during each orbit. Now consider the width at, say, roughly 35 days before the collision. By then, the satellites have changed the “phase of their orbits” so that when one is at the equator (say over the Pacific) the other is at the equator over the Caribbean. At that point, their separation is roughly 6500 km but they are heading toward each other and will pass very close, meaning the y-value of the graph will be close to zero. However, since just 45 minutes before the closest approach, the satellites were very far apart, the graph appears very wide. I’ve added a new graph that shows the details of these two instances in time . I hope this helps explain the graph!

Nicely done, thanks.

>> Something happened to Cosmos 2251 between 1999 and 2003: its orbit unaccountably shifted down to Iridium’s orbit. Perhaps there was a leak of remaining fuel.

>AFAIK (someone tell me if I’m wrong) Cosmos 2251 didn’t have a propulsion system. Maybe it was a battery explosion, rupture of a pressurized compartment, etc.

— Allen Thomson · Mar 24, 12:51 PM ·

Hi Allen,

I asked you about this a while back and your source said he or she didn’t think Cosmos 2251 had a propulsion system. But I’ve done some research since then, and apparently, there’s a distinction in the industry between “propulsion” systems, and “orientation” systems. Propulsion systems are for major maneuvers, whereas orientation systems are mainly for orientation (obviously) but might also be used for minor translocations. Yes, the Cosmos 2251 was equipped with a gravity boom for stabilization, but such passive systems are also sometimes supplemented with active thrusters.

Thus check this out: the first image (bottom) is a photo from a Russian space museum that I think depicts a 1 Newton thruster on a Strela 2M (the same model as Cosmos 2251). The top part of the picture shows the microthrusters used for the Luna 3 mission.

For comparison, the second image depicts some American made 1 Newton thrusters. Note the lack of the traditional “bell” we usually associate with rocket motors.

Note also that the astronautix article on the Strela 2M said that a “hermetically sealed compartment had … guidance equipment mounted at the centre.” Note also that Cosmos 2251 was taken out of service at least 6 to 18 months before its maximum rated lifetime. Therefore, it’s within the realm of possibility that Cosmos 2251 possessed an an active orientation system to complement its gravity boom, and thus such a system would require a fuel tank containing perhaps on the order ~10 kg or more of hydrazine. Since, the satellite was taken out of service early, it’s possible that there was leftover fuel.