I noticed that General David Jones, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1978-1982, passed away at the age of 92.

Richard Goldstein has written an obituary for Jones in New York Times that emphasizes the failure of Desert One under Jones, as well as his subsequent success in consolidating the power of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as enacted in Goldwater-Nichols.

Walt Slocombe wrote in to note that the obituary “ignores one of his main contributions — his stalwart and skillful support of the SALT process. He was terrific to work with, during the Carter administration, in helping Harold Brown shape an agreement the Chiefs would support, and maneuvering to that outcome. He was also just a terrifically decent person to work with.”

Walt argued that Jones was a primary reason the Reagan Administration could not simply abandon the bilateral arms control process. The obituary mentions Mark Perry’s book, Four Stars, which contains an account of the difficult relationship between Jones and Reagan’s first Secretary of Defense, Cap Weinberger.

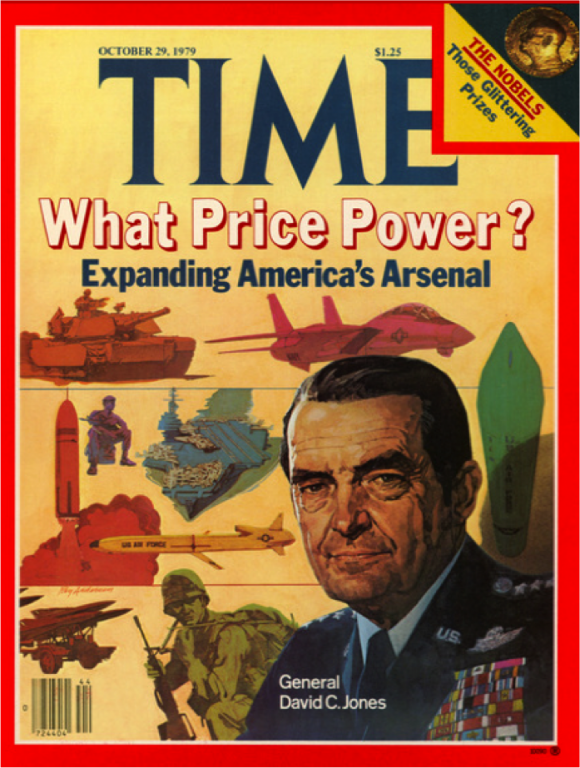

The obituary for Jones in the Washington Post mentions a profile of Jones from Time magazine in 1979, which was part of a longer story on the need to increase the defense budget entitled The Price of Power. (Jones appeared on the cover, above.) Here is the relevant passage, which provides some insight into how Jones was seen during his Chairmanship:

“HE IS EXASPERATED WITH PEOPLE ABOUT HALF THE TIME”

“He gets into an airplane and he just doesn’t know how to turn toward the passenger compartment,” says a senior aide about General David C. Jones. Indeed, during his frequent trips around the U.S. and to many parts of the globe, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff invariably takes charge of the plane’s controls.

Heading straight for the cockpit is a habit that Jones acquired during his 37 years in the Air Force. But he is no mere hot pilot. Cool, meticulous, low-key and dogged, Jones typifies the new breed of military managers. Explains a senior Pentagon aide: “The era is over of flamboyant combat heroes rising to the top of the military. The military is no longer going to win the budget game through image and authority. The brass are going to win it by knowing their stuff and knowing how to present it.”

At this, Jones is an ace. During the current SALT II ratification hearings, he has made numerous trips up Capitol Hill to testify. Leaning intently across the witness table, with rows of ribbons[*] glistening on his four-starred uniform, he has persuasively argued the military case: that SALT II is acceptable if the U.S. increases its arsenal to counter the growing Soviet threat. To a significant degree, it has been the clarity and force of Jones’ arguments that transformed these hearings into a wide-ranging analysis of national defense needs. The Jones touch was also evident in a successful campaign against the Office of Management and Budget; OMB wanted to limit military pay raises to 5%, but Jones got 7%. He has been equally persuasive at the White House, where he helped sell Jimmy Carter on the MX mobile ICBM.

Jones does not win every argument, of course. Indeed, he still bears the scars of the fight over the B-1 supersonic bomber. Carter canceled that project in June 1977, when ex-Bomber Pilot Jones was Air Force Chief of Staff and the plane’s leading advocate. Carter’s surprise decision shook the Air Force. Its generals immediately began talking of mounting a campaign in Congress to save the bomber and they looked to Jones to lead the attack. Jones concluded instead that such a campaign would have almost no chance of succeeding. “That was an agonizing decision,” he recalls today. “Maybe we could have made a better case, but the President had made his decision.”

Some Air Force hard-liners, still smarting from the B-1 experience, have insinuated that the J.C.S. chairmanship was the reward Jones got for going along with the White House. To be sure, Carter, like most Presidents, prizes team players. But the main element in Jones’ selection was the problem-solving managerial talent that he had demonstrated during his four years as head of the Air Force and prior to that as commander in chief of the U.S. Air Forces in Europe between 1971 and ’74.

What was more unusual about Jones’ appointment as the nation’s top soldier was that he neither attended a service academy nor finished college. A native of South Dakota, he dropped out of Minot State in North Dakota in April 1942 to join the Army Air Corps. Ten months later he had his pilot’s wings as a second lieutenant. To his dismay, instead of being sent into combat, he spent the war in the U.S. training other pilots. His combat turn came during the Korean War, during which he flew B-29 bomber missions over North Korea.

His first important staff job came in 1955 at the Strategic Air Command, where he served two years as an aide to its legendary chief, General Curtis LeMay. Jones refers to LeMay as “my mentor.” In 1964, at age 43, Jones decided to learn to fly fighters. He outperformed many of the students who were half his age and went on to command an F-4 Phantom wing. Major posts in NATO, Viet Nam and back at SAC later earned him his stars.

As Chairman, Jones works at least a dozen hours daily, many of them at his stand-up desk in his spacious second floor Pentagon office. Not directly involved in commanding troops, he primarily oversees and coordinates the four service chiefs. He took a speed-reading course to help him through the mountains of paper work, and he writes memos fluently with both right and left hands. “I do it totally unconsciously,” he says of this unusual ambidexterity. “It depends on how I’m sitting or standing.”

Reserved and dignified, Jones is not known to slap many backs or crack many jokes. No one but a few retired generals, especially LeMay, would dare call him “Davey”–at least not to his face. Explains former Air Force Vice Chief of Staff William McBride: “I’ve never seen him slam a desk or shout at anybody. But at the same time, he is exasperated with people about half the time. It is hard to work for him if you’re mediocre. He demands that everybody be as good as he is–and that’s pretty tough.” But Jones can also show tenderness. When ailing, wheelchair-bound Omar Bradley, 86, visited the Pentagon in July 1978, Jones personally took the nation’s only living five-star general on a nostalgic 45-minute tour of the headquarters.

Jones tries to play racketball every day and tries to jog a couple of miles daily. “I ran before it became popular,” he says. He and his wife Lois (they were married in 1942) live in the Chairman’s sprawling official residence at Fort Myer, in Virginia, a short distance from the Pentagon. Their two daughters are living on the West Coast, and their son David, 18, is attending Auburn University in Alabama. “He tells me he wants to be an Air Force pilot,” the Chairman says of his son, and then adds with a smile, “If he doesn’t, he’ll have to go to work.” For one who does not seem to regard the Air Force as work, David Jones has done quite a job.

It’s interesting to think about the battles over the B-1 in the context of what we now know about the B-2. One wonders how many of the Air Force generals knew about the B-2, much less how many in congress.

It points out the dangers of secrecy in that you can’t have a debate about a multi-billion dollar weapons system when no one can talk about it.

In a time when the United States faces almost no plausible existential threat, who are we keeping secrets from?

They knew. Harold Brown mentioned stealth in public during the election campaign after the Carter Administration asked Ben Rich to write a memo to Governor Reagan the possibilities of stealth aircraft. Rich complained about the remark in his memoir.