I am back from London –where I participated in a Track 2 conversation with real live North Korean officials, with Kim Il Sung pins and everything. It was very interesting!

1.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies hosted a n0t-for-attribution Track 2 event at Arundel House. They are preparing a report, but let me make some basic observations.

The event occurred at a very interesting time. The big news, of course, was that North Korea appears to have moved a rocket to the new space launch facility, consistent with its announced intention to place in orbit between12-16 April an earth observation satellite to commemorate Kim Il Sung’s birthday on April 15.

President Obama gave a speech to Hankuk University and press conference at the Blue House in which he made clear that if the rocket leaves the pad, the United States will abandon negotiations on providing nutritional assistance and seek an additional round of UN Security Council sanctions. (Presumably the DPRK will then withdraw its invitation to the IAEA and we will endure another round of sanctions and provocations concluding with a nuclear weapons test. I like a nice loud bang at the end of any performance, so I know when to clap.)

The North Korean participants were excellent. They spoke English very well, spoke extemporaneously from prepared notes, and calmly endured a fair amount of abuse on topic ranging from the florid tone of KCNA statements to the decision to launch this damned satellite. Really, they were as good as interlocutors can be in such a setting.

I came away with the impression that Kim Jong Il himself made the decision to launch the satellite to commemorate Kim Il Sung’s birthday. North Korea may be between a rocket and hard place — there is no way to countermand the order of the late Dear Leader himself, but for some reason they also want to salvage the deal. I am not sure why, after all the nutritional assistance is hardly likely to make a difference in the survival of the regime. Perhaps whoever makes decisions has enough authority to engage the United States but not enough to countermand the Dear Leader’s launch plans. Or maybe the deal’s proponents badly miscalculated, telling whoever makes decisions that they could have their rocket launch and their Plumpy’nut, too.

What is important is that the North Koreans at my meeting didn’t provide any reason to think that North Korea would do anything other than launch that rocket.

2.

My remarks focused on decoding the President’s utterances in South Korea. I observed that the President was clear about abandoning plans for food aid and seeking another round of sanctions. I also explained why I thought the President would, in fact, blow up the deal over this satellite launch. I offered two sorts of explanations.

I started with three substantive points.

- First, all previous North Korean launches have used Nodong and Scud engines. The United States is very concerned about future flight tests of the Musudan IRBM, as well as a possible road-mobile ICBM. If North Korea were to flight-test some of those technologies in a space launch, the Administration would look very foolish indeed.

- Second, North Korea’s right to access space could be satisfied, as it is for the overwhelming majority of parties to the Outer Space Treaty, by the provision of launch services. (In fact, the ratio of satellite operating states:satellite launching states isn’t even close unless you make some fairly ridiculous assumptions about how to count members of the European Space Agency.) Both the ESA and Russia have previously offered to launch North Korean satellites and that a commercial launcher is much less likely to drop the Great Leader’s satellite in the drink.

- Third, sometimes the wise decision is to not exercise a right you might have. South Korea, for example, accepts arbitrary limits on the range of its ballistic missiles, which poses real problems for its own space launch program. I believe that North and South Korea should both refrain from developing indigenous space launch capabilities until the security situation on the Peninsula is rather better.

Then I concluded by noting the political realities for any President negotiating with North Korea. The United States and North Korea have fundamentally different views on the role of the state and the state’s relationship to its citizens. These are profound differences that many Americans and Koreans believe are worth dying to preserve. All we really have in common appears to be a shared desire to avoid a second war to settle those differences, or rather impose our particular answer.

It is difficult for the United States to sustain engagement with a state that most of us would fight to death to avoid living in. “Provocations” is a euphemism for what most of us in democratic countries regard as appalling acts by the DPRK — the murder of so many people aboard the Cheonan and on Yeongpyeong Island and the abduction of Japanese citizens.

I explained that any President has a finite amount of political capital and that an agreement North Korea is a very expensive purchase. No President is likely to expend so much political capital if the prospects for success seem dim. I thought the most telling statement by President Obama at the Blue House was the remark:” frankly, President Lee and I both have a lot of things to do, and so we try not to have our team sit around tables talking in circles without actually getting anything done.” It was a revealing remark made off the cuff and out of frustration. President Clinton chose not to visit Pyongyang in 2000, largely because Sandy Berger was not willing to have the President come home empty-handed for the second time in a month.

So, yes, I explained: Any US President with a modicum of self-preservation would blow up the Leap Day Deal over a satellite launch.

3.

I restricted myself, in the Track 2 discussion, to what I expected would happen, but let’s consider some alternatives.

US officials, including the President, have repeatedly claimed that “we make it a practice not to link humanitarian aid with any other policy issues, particularly in the case of the DPRK.” That’s nonsense. US officials employ a disreputable little circumlocution: North Korea has demonstrated that it cannot make credible commitments, so therefore we can’t possibly provide humanitarian assistance because North Korea might also violate the monitoring arrangements.

At the risk of sounding like a scold, it is immoral to use food as a weapon. If the people of North Korea really need the food, then the rest of the world has an obligation to provide it. As to whether North Korea is capable of making credible commitments or not, that should be left to the NGOs that administer the aid. If North Korea really does divert the assistance to the military or the leadership, the decision to withhold aid should be left to the NGOs. The don’t give a damn about Six Party Talks or missile launches, which is the way it should be.

(You can add this to the list of reasons that I won’t vote for Barack Obama in the fall. I am sure he won’t miss me.)

Sanctions are a more interesting question. UNSCR 1874 is clear on the subject of “any launch using ballistic missile technology.” There is, I suppose, something to be said for not leaving unpunished a violation of a standing UN Security Council Resolution.

On the other hand, we’ve played this game before and it usually ends in another North Korean nuclear test — although, really, the shock value is wearing off. Obama is talking tough about “breaking the pattern” with North Korea, but this is the pattern — and we’re part of it. (Actually, talking about “breaking the pattern” is also part of the pattern.)

Having the Europeans or Russia put the satellite into orbit for the North Koreans is the only face-saving way out for all parties concerned. Unfortunately, if the Dear(ly Departed) Leader approved the launch, then any deviation is probably impossible and, in any event, neither the Europeans or the Russians could get the satellite up in time for Kim Il Sung’s birthday.

The empiricist in me would like to withhold another round of sanctions — what’s one more measly rocket launch among parties to an armistice? — just to see if that would result in a different outcome. At the very least, I am willing to test the hypothesis that Kim Il Sung’s 100 birthday is a particularly sensitive time for any North Korean government, especially one that is only a few months old.

In practice, this would mean continuing discussions about nutritional assistance. On Six Party Talks, the Administration would simply say that we aren’t ready to return to Six Party Talks until North Korea announces a moratorium on long-range missile launches of any kind as demanded by the UNSC, but that we would be willing to include a discussion of the provision of satellite launch services in the Six Party process. After all, the DPRK may have more satellites planned. Hell, they even have a white paper on space development.

4.

I just wanted to share something I mentioned today to lighten the mood a bit. I spent a lot of time defending the United States from accusations of hostile intent toward the DPRK, which I think is a rather one-sided description of the security challenge on the Korean peninsula. I wanted to avoid back-and-forth about who did what to whom and when, although I noted the United States had acted with considerable restraint given the history of provocations from the Cheonan and Yeonpyeong Island all the way back to the seizure of the USS Pueblo in 1968.

Now, about the USS Pueblo. Most years, the Colorado legislature passes a harmless resolution honoring the crew of the USS Pueblo, noting how proud Coloradans are that the ship bears the name of the a city and county in their beloved state and, of course, calling on North Korea to return the ship. It’s really the sort of harmless tribute that is a staple of the American legislative process.

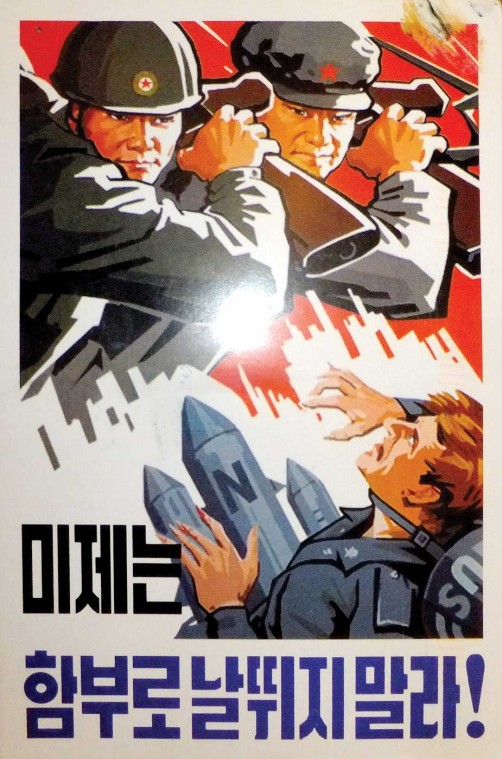

Apparently, someone in Pyongyang felt the need to send the sponsor of the bill a postcard — pictured at the top of this blog post — with this note:

The answer remains No, Never, Not in a million years!

Come and get it! The Korean People’s Army is ready to offer you full hospitality!

Now that is hostile.

Ah, it took me a while, but here’s Ari Fleischer making the same argument about breaking patterns:

“FLEISCHER: No, I think it’s fair to say that when you look at the history of North Korea and its dealings with multiple nations around the world, their approach is the worse they act, the more they get. And that’s an approach that this administration will not be a party to.

And so, I think what you do see in the case of North Korea here is a nation that has had a pattern of acting out of line with international agreements and then seeking to be rewarded by the rest of the world. And the president’s approach to this matter will remain a diplomatic approach, a matter of steady and steely diplomacy.”

Thanks for the report. Still trying to think about how it fits in the current big picture, but very useful to get your perspective.

You and me both.

I wonder if the North Koreans could yield to launching Russian built SLVs from their own facilities..? That way they’d be doing the launch but not getting any missile tech tested as a byproduct.

This is interesting in the context of all sides, actions being constrained by their rhetoric.

The North Koreans seem to realize that the consequences of this launch are not in their best interests, but they’re constrained both by the domestic expectations and the fact that the US is making a big deal about it. Were they to cancel or postpone the launch attempt now it would be apparent that they were bowing to US pressure.

On the other hand, The American government knows that the Killing what appears to be a substantive and positive deal over this is counter productive, but they’re trapped by the realities of election year domestic politics.

In some ways, this situation reminds me of WW1, but hopefully without the millions of dead. What we have here is a urinary ballistics competition that nobody wants, everybody is going to come out worse off for, but nobody feels like they can stop.

Though I agree with Jeffery that it’s unlikely, I still hope that Obama can come out and say in essence “We don’t approve of this launch, but it’s not worth sabotaging the agreement over”.

For the DPRK the issue isn’t the satellite, it is the prestige of launching a satellite.

The far less than successful attempts in the past show that this is no mere test of a missile, or even attempt to humiliate Obama.

It is an attempt by the DPRK to get some respect and attention.

By making a big thing of this attempt to orbit a satellite the enemies of the DPRK – and Obama – are rewarding the DPRK.

Would it not be more sensible to stop rewarding the behavior of a despicable regime?

“there is no way to countermand the order of the late Dear Leader himself”

Really? There’s nobody in charge there now? Who’s actually going to push the launch button then? Maybe he could be persuaded not to. Somebody will make him do it? Maybe that person could be persuaded. Somebody must be at the top of the chain.

Or is it just that the person at the top can’t be persuaded? Maybe it’s a transition year, and he needs some space.

Then again, if the Feb. 29 agreement was a good one for the US, who is making Obama blow it up over a rocket launch?

Perhaps the deal can just be put on hold until the prez has more flexibility.

Seems to me the Norks also have a few more options, such as putting the launch on hold due to a “technical problem.” That doesn’t seem terribly likely, by itself, to provoke the long-suppressed popular uprising against the regime, or a South Korean attack, or even a military coup.

Then again, they could fire it off, and let a “technical problem” decide the matter. Obama might then find a bit more flexibility even in this election year, especially for humanitarian aid.

Seems to me there are any number of ways this one could be solved.

I think the basis of legitimacy for the current ruling arrangement is continuity. Countermanding the Dearly Departed Leader’s orders would be incompatible with that.

And here I was thinking it was hereditary succession.

But surely even the Dear Leader could not have foreseen every possible contingency. Such as, er, a technical problem. Like the one that sent Polyus into the drink.

Mark,

I think you have a vast misunderstanding of the North Korean system. To even hint at the idea of going against Kim Jong Il’s orders would likely mean execution or at the minimum a life sentence at Yodok. His words are considered the equivalent of the words of God; his being dead is immaterial

To elaborate on Jeffrey’s commment: Even in a mature and stable monarcy succession is never strictly hereditary, and the North Korean monarchy is anything but mature and of questionable stability.

Which means, there are a whole lot of powerful people in North Korea seriously wondering, “Are we really going to follow the Kim Dynasty into the third generation, or is it to be political in-fighting, coups and counter-coups, until we figure out who’s really in charge? Jong-un seems like kind of a doofus, but the alternative risks civil war…”

Guessing wrong is likely to be fatal. And publicly breaking with any of the Kim Dynasty’s established plans or policies this soon in the new king’s reign, is likely to be seen as a broader statement of support for the “let’s have a coup” plan.

If someone in North Korea is fool enough to try and make that decision on purely techncial or diplomatic grounds, he’s betting his life on a coin toss that has nothing to do with rockets. Obama might be more flexible and charitable w/re a North Korea that doesn’t launch rockets, but he’s not going to send in Seal Team Six to extract the North Korean general who declined to launch a rocket and is now on the wrong side of a coup. The safest course of action for that guy, is to press the damn button and wait to see what everyone else does.

And pray for the rocket to make orbit, because even a genuine technical failure will be viewed by some as a sort of political statetment against the dynasty.

“And pray for the rocket to make orbit, because even a genuine technical failure will be viewed by some as a sort of political statetment against the dynasty.”

I tried this one on the North Koreans — who wants to be responsible for dropping the Great Leader’s satellite in the drink? Let’s the Russians do it!

Well, I’m as amazed at the willingness of so many erstwhile hard-liners to make excuses for the North Korean dictatorship as I am at my own inclination to hold it responsible for its actions.

The consensus here seems to be that there really is nobody actually in charge over there, nobody who can make a decision and color it any way that may be needed (as autocracies are wont to do). Well, that may be the case, but I doubt it. Let’s assume Kim Jr. Jr. doesn’t command the loyalty and fear of the inner circle as his dad did — yet. But then that inner circle is the actual ruling body, isn’t it? What you all are saying is that it is unlikely to change course, and I would agree with that, but not that it is unable to.

Perhaps the system really is completely frozen and running on automatic pilot for the moment. I’m not sure we know that. Even if it looks that way from the outside.

But for the record, my suggestion about ditching the rocket as a sensible way to change course was that this could be done covertly by an inner conspiracy, as I suspect (without knowing) the KGB may have been asked to dispose of a certain harebrained project which would have played directly into Reagan’s hands if it hadn’t been unaccountably lost.

Also, for little Kim to suggest a deviation from the Dear Leader’s charted course might not play to his favor in the long run, but I doubt it would result in his immediate execution.

Mark:

The situation is more subtle than this. The problem isn’t that Kim Jong Un would be executed, rather the problem is that stopping the launch would be inconsistent with the argument put forward for his succession — continuity — within the elites who control the country. Neither Kim, nor the people around him, have any incentive to raise the issue of deviating from Kim Jong Il’s instructions. Most people I talk to think the first major test of this transition will be when Kim (or the regent or ruling clique) confronts a situation that requires a fresh decision that makes winners and losers on its own. That’s a big test — and there is no reason to rush it.

You suggest North Korea make this decision covertly, by “inner conspiracy”, but it is the “inner” leadership that might crack over a fresh direction in policy that deviates from where Kim Jong Il left things.

Look, there is an old joke about leadership transitions in business:

Kim Jong Un would be wise to remain under the protection of the first envelope as long as possible.

NK friends want me to pass you a correction: The Dear Leader has NOT departed — he is merely in a sleeping competition and is, in fact, winning.

So, he’s as good at sleeping competitions as golf?

On a more serious note Prof. Walt at Harvard en estados unidos has interesting take on Arms Control generally — diplomacy vs. coercion? :

http://walt.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2012/03/29/whatever_happened_to_arms_control

Prof. Walt’s comments seem somewhat strange. The current blow-up is because the US *did* go negotiate (quietly, so as to avoid public pressure on either side) a deal with NK on them stepping away from a bunch of provacative things relative to arms control and proliferation, and them getting real aid in return. And then, along comes the rocket launch.

The opinion seems to miss the last couple of weeks developments.

Without getting everyones’ knickers in a twist — and without really knowing what he’d say — I’d venture that Prof. Walt would view restrictions on NK SLVs/ICBMs a bit rich, even if they were obtained by a sanitized political coalition of the victors of WW II. Probably he’s emphasize that we should ratify the CTBT before preaching to others. Just guessin’.

His point seems larger than this silly spat.

Even in the larger context, huge amounts of diplomacy and IAEA wrangling have preceded what’s going on with respect to Iran now.

Ultimately, for issues judged of sufficient national interest by someone, force will rule if diplomacy fails. This is not news to anyone. It’s been a cardinal rule of geopolitics since the term was defined (see “Great Game”). It’s fair to say that no party – the US included – is great at diplomacy. It’s not fair to say that we haven’t tried with either NK or Iran.

On an even narrower note, Walt seems to distinguish the New START treaty from previous arms-control treaties that altered “the basic strategic relationship.” I’m still trying to stretch my memory on that one.

Is anyone interested in State’s refusal to answer when asked if NK gave the US a headsup on the launch during the earlier talks that led to the February agreement? I understand nobody pays attention when NK says it did, but why won’t the US deny or confirm it?

Regarding Jeffrey’s statement: “UNSCR 1874 is clear on the subject of ‘any launch using ballistic missile technology’.”

Let’s be careful how we interpret SCR 1874. In fact, the pertinent language there was “demand,” which is not a mandatory language, and thus not binding.

What is binding in the resolution is the suspension of “long-range missile program.” There is room to argue that this prohibition did not specifically include satellite launch, which is entitled by all nations.

Hmmm. I am not sure that is precisely the standard.

The important language in Chapter 7 SC resolution is “decides.”

This, what is binding is the following paragraph:

“3. Decides that the DPRK shall suspend all activities related to its ballistic missile programme and in this context re-establish its pre-existing commitments to a

moratorium on missile launches;”

It can be argued, in the absence of a specific prohibition

against “satellite rocket launch”, the SC prohibition was

only against any “ballistic missile program” in the context of military missiles.

Another legal issue not discussed is whether SC has the power to prohibit a UN member country to suspend its

missile programs when the particular country deems

such a program essential to its national security ans

such test is carried out in a secure manner.

Thus there is also some question whether SCR 1874 was

adopted illegally in violation of the international law.

This is particularly so when the P-5 countries enjoy their right of testing many ballistic missiles any time.

All members of the UN are supposed to enjoy equal rights.

I am not so sure about your legal interpretation.

After all, the relevant language relating to enrichment in Iran is also “demands.”

I think “demands” means, you know, “demands.” I don’t see any basis for the assertion that “demands” simply means “suggests.”

Whether the resolution violates international law is not relevant to the question of what the resolution says, which happens to be very clear.

UNSC resolution 1874 was adopted right after the launch of Unhya-2 in 2009. It was drafted precisely to close the loophole that existed in resolution 1715 of 2006. OP2 was amended from demanding that the DPRK do not launch ballistic missiles to demanding that the DPRK do not conduct a launch using ballistic missile technology. It was amended precisely to prevent the DPRK from arguing that the resolution did not apply as what was launched was not a ballistic missile.

Now, you may want to argue that the term “demand” in a UNSC resolution taken under Chapter VII is not binding, but this is certainly contrary to the view of UN member states. You can go and check the opinio juris of UNSC members when they adopted the resolution. Also, the fact that OP 2 is considered as binding by UN member States at large (and not simply the P5) is also clear, and have led quite a lot of them to inform the DPRK that as a result they will not be represented at the celebrations for the centenary of Kim the eldest (whereas they had initially accepted the invitation).

Thank you so much for such well thought ideas. I think Obama will never forgive North Korea who stole his historic Prague show on April 5, 3 years ago. NK is the only party who hit back his no-nuke speech with missile launch.

Jeffrey, I’m not sure referring to the Armistice in this regard is wise: “what’s one more measly rocket launch among parties to an armistice?”

After all, who was it that unilaterally abrogated, aka broke, paragraph 13(d) of the Armistice to first deploy nuclear weapons and missiles in Korea? I was a bit surprised you didn’t mention 13(d) in your Honest John post a couple of weeks back.

I’m intrigued to know if anyone mentioned the Armistice in your Track 2 event, and if your visitors responded with the paragraph 13(d) episode?

NB I found a good bit of 1958 newsreel of the first Honest John and “280mm atomic cannon” deployment in Korea:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVTW36xxaBY#t=02m32s

That must have been less than a month after they deployed – no attempt to keep it fairly quiet for a decent period after abrogating 13(d) to avoid obvious linkage and annoying the other side!

First, I chose the phrase to mirror “among friends” — with the obvious joke being that we are hardly friends. At best, we’re armistice partners.

Second, you raise an interesting point about the moment when the UN Command — in 1957 — announced that it no longer felt bound by 13(d). Here is an account from 1957. Obviously, it is a bit one-sided.

I’ll see if I can find any declassified documents on the decision to abandon 13D.

On a funny note, notice the “neutral” nations — two neutrals (Sweden, Switzerland) and two Warsaw Pact (Poland and Czechoslovakia). At our Track II, the North Koreans complained that the neutral nations had all joined NATO. A colleague of mine, being a staunch defender of Swedish neutrality, was irritated enough to correct the record. of course, Poland and the Czech Republic (as well as Slovakia) are members of NATO, which led that colleague to recommend that the North Koreans designate two new representatives to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission. That seems like a reasonable recommendation to me.

Thanks, I’d like to see the declassified documents on the decision to abrogate 13(d).

I’ve been looking at this recently, and the best paper I’ve found sourced on the declassified documents is:

Lee Jae-Bong, “U.S. Deployment of Nuclear Weapons in 1950s South Korea & North Korea’s Nuclear Development: Toward the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 8-3-09. (15 December 2008 (Korean), 17 February 2009 (English)).

http://www.japanfocus.org/-Lee-Jae_Bong/3053

Naturally enough, it does not match the TIME magazine account! It does have at least two flaws:

1) The Korean author seems unaware of the publicity given to the atomic deployment in 1958, such as in the newsreel linked to above. It appears there was no public publicity given in the South Korean media.

2) The author seems to conflate the Yongbyon IRT-2000 and Magnox 5MWe reactors, and does not discuss the other Magnox reactors halted by the Agreed Framework.

Pointers to other good papers on 13(d) welcome.

At least since this earth observation satellite will be placed in a polar orbit, its launch trajectory should not pose a threat to Japan.