This is a guest post by Ariana Rowberry, Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellow with the Arms Control and Nonproliferation Initiative, Brookings Institution.

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is preparing for the arduous task of removing and destroying Syria’s chemical agents and infrastructure. This task faces numerous complications. The chemicals must be sealed and packaged, transported across insecure territory on questionable infrastructure, loaded on two cargo vessels, one belonging to Denmark and one to Norway, at the port of Latakia, which will then transport the chemicals to an Italian port, where they will be transferred to a cargo ship under control of the U.S. Navy.

Here, Syria’s estimated 500 tons of “priority 1” chemical agents—including mustard, VX, and sarin gas and their associated components—will be destroyed at sea, using a Field Deployable Hydrolysis System, a technology that will dilute the chemical agents to a low-level toxicity. The process of hydrolysis has previously been used in the destruction of chemical agents; however, using such a mobile system at sea is unprecedented. The United Nations decision to destroy Syria’s most dangerous class of chemical agents at sea was made after no country volunteered to host their destruction.

What is a Field Deployable Hydrolysis System and how will it operate at sea?

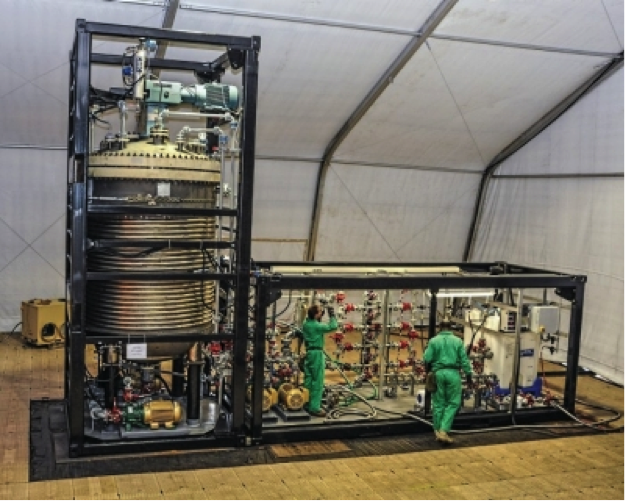

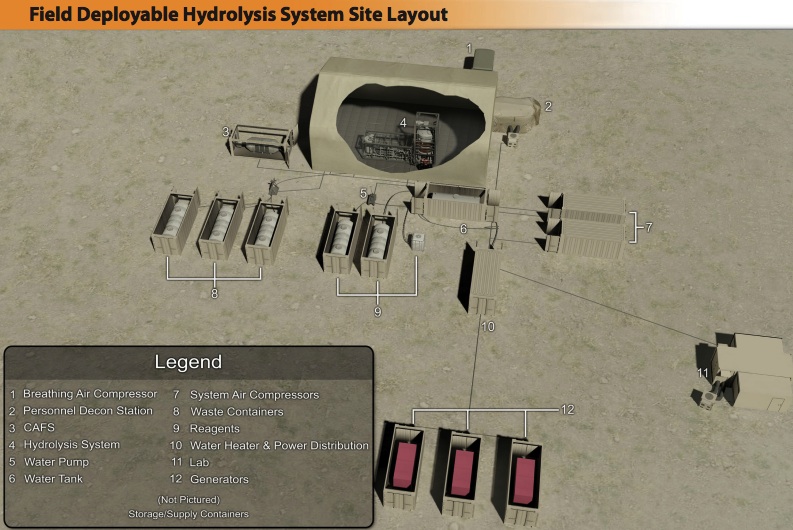

The Field Deployable Hydrolysis System (FDHS) was developed by the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (ECBC) in conjunction with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Development for the system began last winter after senior officials within the Pentagon assembled a senior group to look at technologies that could be applied to Syria’s chemical weapon stockpile. Final testing for the system concluded this summer. A total of seven FHDS systems are expected to be developed. Currently, three units exist, two of which will be used in the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons. One FDHS is roughly the size of two shipping containers.

The two FDHS will be placed on the motor vessel Cape Ray, a cargo ship that is part of the United States’ Maritime Administration’s ready reserve force. The ship has undergone special renovations at Norfolk, Virginia to host the FDHS capability. The FDHS systems will be placed below deck complete with carbon filters and an analytical laboratory. The FDHS is able to be deployed anywhere in the world within ten days and takes a crew of 15 individuals to operate. Around 100 people will be aboard the Cape Ray, comprised of civilians and contractors from the Department of Defense, in addition to members of the OPCW.

How does the Field Deployable Hydrolysis System Work?

The FDHS uses water, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and heat to neutralize the chemicals with 99.9 percent effectiveness. The chemicals are broken down in a 2,200-gallon titanium reactor. The system has the capacity to destroy between 5 and 25 tons of chemical agent per day. Therefore, the FDHS has the potential capacity to destroy Syria’s priority 1 chemical agents within 45 to 90 days.

The waste resulting from the dilution of the chemicals will be stored on board the Cape Ray, assuaging environmental concerns that the effluent could be dumped into the sea. The FDHS generates between five and fourteen times the volume of chemical agent being destroyed. After the chemicals are diluted, the effluent can be commercially stored.

The FDHS is self-sufficient, complete with its own power generators, personnel decontamination station and chemical agent filtration system. The FDHS will only need the outside resources of water, reagents and fuel to operate.

A proven technology or cause for concern?

The international community considered alternative technologies to destroy Syria’s chemical agents, including incineration. However, the FDHS was ultimately selected, given the United States’ extensive experience destroying chemical agents through hydrolysis, including at the former chemical weapons sites at Newport, Indiana and Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland during the 2000s. According to officials in the Department of Defense, the FDHS is a “proven technology.” The only change is that this technology is now mobile.

However, some chemical weapons experts are expressing concern. Raymond Zilinskas, director of the Chemical and Biological Weapons Nonproliferation Program at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies remarked that, “There’s no precedence. We’re all guessing. We’re all estimating.” Mr. Zilinskas also drew attention to the fact that no assessments of possible environmental impact are being conducted, as would be done if the chemicals were destroyed on land. Despite these concerns, it appears that, given the security and diplomatic complications, paired with a strict time frame for the complete elimination of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile, the FDHS provides a relatively low-risk alternative for ridding Syria of its most dangerous chemical agents.

So do I understand correctly that MV Cape Ray will finish this process with up to 7,000 tons of effluent containing half a ton of residual nerve and blister agents?

The ship is physically large enough for such a cargo, but she isn’t a tanker and I don’t see any indication of the major modifications that would seem to be called for. Or are they just taking aboard 50,000 50-gallon drums and hoping for no leaks?

And then renaming the ship “MV Flying Dutchman”, on account of all the ports of the world will be closed to her forevermore…

I have written a detailed description of how the Cape Ray will be configured in order to deal with the effluent at

http://www.the-trench.org/sea-based-destruction-of-syrias-cw-proposed/

Besides the installation of containers to capture effluents in the lower holds, empty containers that have held reagents for the neutralisation processes will be re-used to hold effluents too.

No, if it is what I think it is, the agents are simply broken down with bleach and lye.

The resultant effluent would be much kinder to the ocean compared to how we did things previously, btw.

My concern is threefold:

First, you are opening up yourselves to attack. Are adequate safeguards in place?

Second, are they selling the chemicals off much as possible? Not all precursors have a singular use.

Lastly, surely *we* aren’t gonna be responsible for the trash, right? Syria caused it, Syria should be responsible for final treatment and discharge.

Shawn

Why shouldn’t we be responsible? We actively supported Saddam Hussein. CW program, from providing him the chemical precursors to blaming Iran. On it’s other side, ces Israel, which has a nuclear arsenal it maintains with US connivance.

We are the largest supplier of arms to the world and to the Middle East. Even if we weren’t violating our own laws by supporting WMD users, we share in the responsibility when, inevitably, heavily armed dictators kill civilians, abuse human rights, or wage wars of aggression against their neighbors.

@ Shawn Hughes

1. Are we opening ourselves to attack, and are there proper safeguards in place?

It seems that once the chemicals are aboard the Cape Ray, potential for attack will be relatively low. The vessel will be protected by the US Navy. It was also just announced the PLA navy will be providing a ship to assist with security. The real danger is transporting the chemicals from the current locations within Syria to the port at Latakia.

The current plan provides for Russian armored trucks to transport the chemicals. The Russian trucks will be supported by the Syrian troops and tracked by American satellites. The path that the Russian trucks will take is unknown, but infrastructure is a key concern. Due to heavy fighting, a major road between Damascus and Homs has been closed. Additionally, as noted by Amy Smithson, senior fellow at the Center for Nonproliferation studies: “The threat in this process is on land in Syria. Syria is overrunning with fighters of all types- Hezbollah, Hamas, Al-Qaeda. And they might want to get their hands on these chemicals.”

2. What will be done with the effluent?

The waste will be kept on the ship until they are disposed of commercially at waste treatment facility. Pending issues with funding, the OPCW will begin a tender process for commercial firms interested in destroying the effluent. Commercial firms will also destroy Syria’s “priority 2” chemicals. A tender process for these chemicals began today- around 30 firms have put in for bids, and the OPCW is likely to choose one or two.

The question of responsibility is an interesting one. Under the OPCW Executive Council’s Nov. 15 decision, EC-M-34/DEC.1 (operative paragraphs 4 and 5), Syria “maintains ownership of its chemical weapons until they are destroyed, wherever the destruction might take place,” but “upon removal of declared chemical weapons from its territory, the Syrian Arab Republic no longer has possession, nor jurisdiction, nor control over these chemical weapons.”

While I don’t necessarily disagree with the sentiments expressed, and it’s nice that the FDHS is getting some attention, this is an oddly un-analytical post. Most importantly, what’s the basis for the conclusion that “the FDHS provides a relatively low-risk alternative for ridding Syria of its most dangerous chemical agents”? It might be worth fleshing that out at least a little.

This is fairly proven technology. There’s been some news regarding the use of this chemistry to process a human body in lieu of cremation. It’s a very powerful and thorough chemical reaction.

Another very powerful process that could be tried is Fenton’s Reaction using concentrated hydrogen peroxide and iron. This has been used by the DOE to destroy ion exchange resin beads that had been used to adsorb radioactive ions from wastewater. (The radioactives were recaptured in another process.)