Once [Follow-On To Lance] had been cancelled [in May 1990], as well as the upgrade for nuclear artillery, and the INF Treaty had eliminated all longer-range missiles, only dual-capable aircraft remained available for SACEUR’s use as a nuclear deterrent. The rancor raised by the FOTL debate carried forward in to a broad public concern over any nuclear forces, thereby putting the spotlight on [dual-capable aircraft]. In response, NATO chose over the next 15 years to minimize public discussion or awareness of this aspect of its deterrent mission.”

— Jeffrey A. Larsen, The Future of U.S. Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons and Implications for NATO: Drifting Toward the Foreseeable Future (2006)

Make that 20 years. For about a generation’s time now, the North Atlantic alliance has been drifting, in Larsen’s words, “toward the withering away of its nuclear capabilities.” Nuclear debates have been deferred indefinitely, leading to the present situation, wherein acquisition decisions (or non-decisions) have long substituted for fundamental policy choices.

But now we’re having the discussion, which at times has manifested as a semi-public debate between the German Foreign Ministry and the German Defense Ministry. Behold the nuclear side of what SecDef Gates recently dubbed “the demilitarization of Europe – where large swaths of the general public and political class are averse to military force and the risks that go with it.”

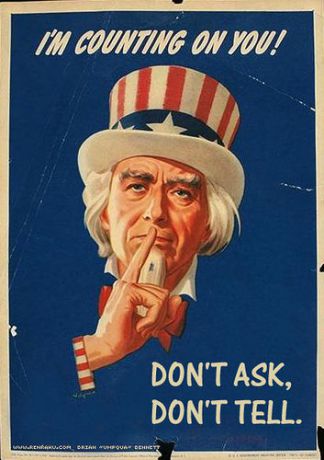

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Now that the argument has finally commenced, the official silence and habitual secrecy surrounding the exact numbers and whereabouts of NATO’s bombs must rank among the quirkier legacies of the Big Shhh that descended years ago over U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. Consider this passage from the above-cited study by Larsen, which was sponsored by NATO:

Most estimates claim that there remain several hundred U.S. tactical nuclear warheads in Europe, at some eight bases in six European nations that could be delivered by a fleet of dual-capable aircraft (fighter-bombers) manned by up to eight allied nations. [5]

[5] See, for example, Hans Kristensen, U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: A Review of Post-Cold War Policy, Force Levels, and War Planning (Washington: Natural Resources Defense Council, February 2005); Kristensen and Stan Norris, “NRDC Nuclear Notebook: U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2006,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January/February 2006, pp. 68-71; and Brian Alexander and Alistair Millar, eds., Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Emergent Threats in an Evolving Security Environment (Washington: Brassey’s, 2003).

Or this passage from an instant classic of Shhh, a February 2010 paper by Franklin Miller, George Robertson, and Kori Schake:

According to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), the US possesses about 1,200 tactical nuclear weapons, of which 500 are operational warheads (the rest are in storage or in the process of being dismantled). The FAS indicates that 200 of the operational weapons are deployed in Europe, stationed with US and allied air crews in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy and Turkey. [2]

[2] Federation of American Scientists, http://www.fas.org/blog/ssp/2009/03/russia-2.php.

Now, George Robertson used to be NATO’s Secretary-General. Who supposes that he needs Hans Kristensen & Co. to tell him where the bombs are?

This sudden deference to NRDC or FAS is the NATO equivalent of a phrase that appears, in some version, in every Israeli news report or commentary about Israel’s “nuclear option”: According to foreign media… That fig leaf is enough to keep the military censor out of the hair of reporters and editors.

Jive Turkey

Speaking of figs, NATO’s extreme case study in formal opacity may be Turkey, where, as Alexandra Bell has reported, military officials are far from ready to concede the obvious:

Turkish officials were cagey about discussing these weapons. A former Air Force general, following what seemed to be the official line, denied that there were nuclear weapons in Turkey, saying they were removed at the end of the Cold War. This differed from the other officials I met, whose wink-wink references basically confirmed the presence of the nukes. They also hinted that the weapons would be critically important if a certain neighbor got the bomb.

Turkish civilian officials, as ACW’s own Jeff Lewis has gathered, seem to take an altogether different view on the importance of U.S. nuclear weapons hosted abroad. Turkey may be as divided as, say, Germany on the matter.

There’s a limit to the comparison, of course: Germany isn’t undergoing the revolution in civil-military relations that is Turkish political life today.

Latest News: Cold War Still Over

But enough talk about talking about not talking. Whether to act — to withdraw an undisclosed number of tactical nuclear weapons from undisclosed locations in Europe — will be on the agenda of the conference of NATO Foreign Ministers next month in Tallinn, Estonia. It should be mighty interesting. This comes on the heels of a Japanese decision to disavow explicitly any claim to standing over American decisions on tactical nukes, and a Japanese news report alleging that the Americans have, as a courtesy, telegraphed an upcoming decision on that front. We’ll have to wait and see if that’s really so.

Whenever it comes and however it comes, change is coming. As with strategic weapons, but perhaps moreso, the ground has shifted around tactical nuclear weapons. Kids today have no idea what’s meant by the Fulda Gap — trust me on this one. But everyone’s heard of Osama.

For further reading: Pavel Podvig and yours truly at the Bulletin.

I sometimes wonder. Why the obsession with a few ol’ B61s? Why are so many analysts seemingly more concerned with them than with, say, Russian TNW? And why not more interest in having transparency on the US arsenal as a whole (as opposed to an interest in transparency on a very, very limited portion on that arsenal)?

The Fulda Gap argument is a tad tiresome. Anyone who has discussed the matter in NATO circles knows that no one in Brussels or Evere expects to fight any war with these weapons. Those who should be told that the Cold war is over are on the right-hand side of the continent, not on the left-hand side.

The real issue is what you lose (if anything) by withdrawing the B61s, especially unilaterally. Agree with Josh that all should rejoice that the debate is now open.

Indeed, now that the debate is open it should progress at an almighty pace as a new paper by Malcolm Chalmers and former NATO Parliamentary Secretary Simon Lunn make clear.

Especially interesting is the fact that the German capability to deliver these weapons will disappear, with no planned replacement, as soon as 2012. Looks like NATO’s in for some interesting times…