What better occasion than Christmas to ponder nuclear terrorism?

According to a Dec. 19 story by Thom Shanker and Eric Schmitt in the New York Times, the forthcoming Nuclear Posture review will be just as much about preventing nuclear terrorism as about nuclear deterrence.

It’s a good idea, and — in hindsight — a perfectly natural one after the last decade’s worth of discussions of the role of “non-state actors.” But there’s a difficulty in the mismatch between counterterrorism and the notions that ordinarily fall under the rubric of nuclear posture: weapons systems, platforms, bases, stockpiles, alert rates, infrastructure, and so forth. So, the Times reports, the idea will translate to more support for intelligence and forensics.

Oddly, though, the story doesn’t mention the one “core” area of nuclear posture that does relate directly to the threat of terrorism, and always has: the security of U.S. nuclear weapons.

To get a sense of how much a chestnut this is — there’s the holiday, again! — look no further than the latest release in the Foreign Relations of the United States series, Documents on Global Issues, 1973–1976. Steven Aftergood of FAS Secrecy News helpfully points out the most interesting item — at least for readers of this blog — an Intelligence Community report from 1976 on the threat of nuclear terrorism.

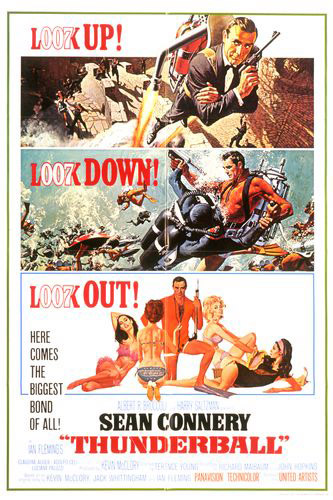

The authors concluded that terrorist groups were unlikely to try to acquire nuclear weapons in the near future, mainly for reasons that no longer apply in 2009 — most importantly, the “internally generated limits to the level of violence they are willing to inflict.” Apparently for the same reason, the authors saw the residual nuclear terrorist threat mainly through the lens of Thunderball-type blackmail scenarios, a view that most terrorism experts probably don’t share today:

By the nature of terrorist behavior patterns, we believe that some form of indirect use of nuclear explosives is more probable than direct use. Specifically, a major motivation for terrorist seizure of a nuclear weapon would be to acquire a credible threat for blackmail and/or publicity. It is judged that most terrorist groups attempting to seize a weapon would do so without the specific intention of detonating it. In an extreme situation, however, some might attempt a detonation.

But never mind. Just where would the terrorists get their nefarious device, assuming they were to try to seize a complete weapon? After consulting a playbook found in the stateroom of the Disco Volante, why, the answer is “NATO,” of course:

If an attempt at seizure of a weapon was made, the one targeted would probably be a US weapon deployed abroad…. This is true not only because of the wide deployment of such weapons but, more importantly, because of the great political importance assigned by terrorists to targets involving the US presence abroad…. We note that all US weapons deployed abroad have control devices of varying degrees of sophistication that are designed to insure weapon safety or to preclude unauthorized use and that would require time and effort to overcome.

PALs are your friends, but not a panacea. And as Bob van der Zwaan and Tom Sauer recently reminded us in the Bulletin, security at some NATO facilities that store nuclear weapons isn’t up to snuff.

The precise implications of this concern for a Nuclear Posture Review focused on preventing nuclear terrorism are left as an exercise for the reader.

In the meantime, happy holidays! Here’s a little something for your enjoyment.

Re: the conclusion

“If an attempt at seizure of a weapon was made, the one targeted would probably be a US weapon deployed abroad”

— This is not so far-fetched. There were real concerns about the security of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe at the time this was written. On a trip to NATO in 1974, Sen. Sam Nunn was told privately by a group of sergeants at a base in Germany that the weapons were indeed vulnerable (although commanders had given Nunn a presentation that all was well.) The problem at the time, as it was explained to Nunn, was people: serious drug and alcohol abuse among the demoralized military guarding US tactical nukes abroad. Nunn was shaken by the visit, and the experience played a role in the origins of Nunn-Lugar after the 1991 failed coup in Moscow. See my book, The Dead Hand, p. 381.

From the NYT article:

“The Obama administration’s review, in addition to elevating the threat of nuclear terrorism, also calls for strengthening deterrence — and strengthening America’s “extended deterrence” to protect allies — while reducing the roles and numbers of nuclear weapons over coming years.”

I doubt there will be a significant change in policy.

Also, as regards nuclear terrorism, the threat is somewhat overhyped.

John Mueller’s new book Atomic Obsession provides some good background on the subject

“….our current worries about terrorists obtaining such weapons are essentially baseless. As Mueller points out, there is a multitude of reasons why terrorists will not be able to obtain weapons, much less build them themselves and successfully transport them to targets. Mueller goes even further, maintaining that our efforts to prevent the spread of WMDs have produced much more suffering and violence than would have been the case if we took a more realistic view of such weapons. This controversial thesis cuts against the received wisdom promulgated by America’s enormously powerful military-industrial complex. But given how wrong that establishment has been on so many crucial issues over the course of the entire post-World War II era, Mueller’s argument is one that deserves a wide public hearing.”

Reviews

“With his rare combination of wit and meticulous scholarship, John Mueller diagnoses that America is paralyzed by atomaphobia and prescribes a fifteen-chapter treatment to help us recognize that we have blown reasonable concerns about weapons of mass destruction and terrorism out of proportion and that many of our policy responses actually make things worse. Atomic Obsession is recommended bed-time reading for nervous Nellies both inside and outside of government.”—Michael C. Desch, author of Power and Military Effectiveness: The Fallacy of Democratic Triumphalism

“John Mueller’s argument will almost certainly change your interpretation of some significant events of the past half-century, and likely of some expected in the next. It did with mine.”—Thomas C. Schelling, 2005 Nobel Prize Laureate in Economics and author of Arms and Influence

“With clear-eyed logic and characteristic wit, John Mueller provides an antidote for the fear-mongering delusions that have shaped nuclear weapons policy for over fifty years. Atomic Obsession casts a skeptical eye on the nuclear mythology purveyed by hawks, doves, realists, and alarmists alike, and shows why nuclear weapons deserve a minor role in national security policymaking and virtually no role in our nightmares. It is the most reassuring book ever written about nuclear weapons, and one of the most enjoyable to read.”—Stephen M. Walt, author of Taming American Power

“…the book will certainly make you think. Added bonus: It’s immensely fun to read.” — Stephen M. Walt, ForeignPolicy.com

“Mueller’s achievement deserves admiration even by those inclined to resist his central thesis. The book is meticulously researched and punctuated with a dry wit that seems the perfect riposte to the pomposity of security experts who have so far tyrannized debate. Although by no means the last word on nuclear weapons, Mueller deserves praise for having the guts to shout that the atomic emperor has no clothes… the book should nevertheless be packaged up and sent to Presidents Barack Obama and Nicolas Sarkozy and Prime Minister Gordon Brown with a simple message: ‘Please calm down.’” —Arms Control Today

“….our current worries about terrorists obtaining such weapons are essentially baseless”

Wow-That’s quite a statement. Whether it “cuts against the preceived wisdom promulgated by America’s enormously powerful military-industrial complex”, to say that it’s “baseless” really reflects this person’s ignorance of the threat.

Suppose, for example, we have Pantex eliminate all the security & safeguards they maintain to protect against this “baseless” treat? Perhaps, the threat represents a lowered risk because of the serious resources deployed against this threat.

Just because this threat has not occurred (yet) does not mean it’s “baseless”.

I think one thing has been completely missed here. According to the NYT article countering nuclear terrorism is being elevated as a central component of the NPR. Why? The article provides the underlying rationale, “At the core of this threat, which officials say has been growing steadily since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001,…”.

Because the threat has been “growing steadily” since 9/11 it is now necessary to make countering nuclear terrorism a central plank of US strategic planning. But, has the threat really been “growing steadily” since 9/11? You don’t have to believe Muller’s “baseless” claim to express scepticism about this underlying premise. Most jihadis see 9/11 as being a set back (see Brynar Lia’s analysis in the book on al Qaida strategist Abu Musab al-Suri and Fawaz Geges on “Why Jihad Went Global”) which has seriously affected their operational capabilities; that would mean the threat has decreased since 9/11. John Kerry just released a hatchet job against Bush on the battle at Tora Bora. It opens with an account, pre 9/11, of Zawahiri and bin Laden rejecting a delegation of Pakistani scientists telling them “soon” something big will happen. In other words Sen Kerry’s report tells us al Qaida rejected nuclear terrorism, pre 9/11, as being too hard. So why should now it actually become steadily easier for them post 9/11 given that al Qaida is on the run? It doesn’t make sense. Was Aum Shinrikyo on the run prior to the Tokyo sub-way attack?

Such books don’t appear in the standard nuclear terrorism genre because the study of nuclear terrorism is dominated by the US arms control and non-proliferation community who practice a type of apolitical politics. So all the emphasis is on fissile material security, PALs etc.

I notice that David Hoffman has a comment here. In his book “The Dead Hand” he has a comment from Ashton Carter who, correctly, points out that nuclear security is ultimately socially embedded. The US sent over some money for Nunn-Lugar but supported Yeltsin’s near destruction of Russian society. Obama is now destabilising Pakistan by expanding drone attacks etc. These political issues have primacy over the other stuff.

I’m writing a book on nuclear terrorism myself so will leave all that at that.

Secondly I don’t know whether the USSR had a dead hand or not. But, as an aside, think of Gene Hackman’s character in the movie “Crimson Tide”. For him there is no role for judgement. He is just a cog in a step-by-step algorithmic process. You can have a nuclear command and control system that is not mechanised but still largely functions as a computer to the extent that it is algorithmic, with no role to be played by judgment. It’s like the way a computer plays chess, i.e. without judgement.