The world knows what successful cooperative disarmament looks like. When a country decides to disarm, and to provide to the world verifiable evidence that it has disarmed, there are three common elements to its behavior:

- The decision to disarm is made at the highest political level;

- The regime puts in place national initiatives to dismantle weapons and infrastructure; and

- The regime fully cooperates with international efforts to implement and verify disarmament; its behavior is transparent, not secretive.

Or not. Apparently, we wouldn’t know what disarmament looked like if we intercepted the order.

Because we did.

That argument appears in a book-length classified report and unclassified article in Foreign Affairs by Kevin Woods, James Lacey and Williamson Murray:

By late 2002, Saddam finally tilted toward trying to persuade the international community that Iraq was cooperating with the inspectors of UNSCOM (the UN Special Commission) and that it no longer had WMD programs. As 2002 drew to a close, his regime worked hard to counter anything that might be seen as supporting the coalition’s assertion that WMD still remained in Iraq. Saddam was insistent that Iraq would give full access to UN inspectors “in order not to give President Bush any excuses to start a war.” But after years of purposeful obfuscation, it was difficult to convince anyone that Iraq was not once again being economical with the truth.

Ironically, it now appears that some of the actions resulting from Saddam’s new policy of cooperation actually helped solidify the coalition’s case for war. Over the years, Western intelligence services had obtained many internal Iraqi communications, among them a 1996 memorandum from the director of the Iraqi Intelligence Service directing all subordinates to “insure that there is no equipment, materials, research, studies, or books related to manufacturing of the prohibited weapons (chemical, biological, nuclear, and missiles) in your site.” And when UN inspectors went to these research and storage locations, they inevitably discovered lingering evidence of WMD-related programs.

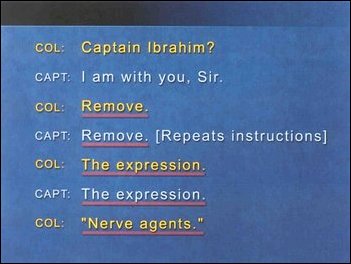

In 2002, therefore, when the United States intercepted a message between two Iraqi Republican Guard Corps commanders discussing the removal of the words “nerve agents” from “the wireless instructions,” or learned of instructions to “search the area surrounding the headquarters camp and [the unit] for any chemical agents, make sure the area is free of chemical containers, and write a report on it,” U.S. analysts viewed this information through the prism of a decade of prior deceit. They had no way of knowing that this time the information reflected the regime’s attempt to ensure it was in compliance with UN resolutions.

What was meant to prevent suspicion thus ended up heightening it. The tidbit about removing the term “nerve agents” from radio instructions was prominently cited as an example of Iraqi bad faith by U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell in his February 5, 2003, statement to the UN.

Walter Pincus has a nice summary in the Washington Post.

Was the misinterpretation of the instructions to remove references to nerve agent, “ironic” or intentional? Considering the “misinterpretation” of the oh-so-obviously forged Niger documents, I don’t think we can give the benefit of the doubt to the Bush administration.