Barton Gellman of the Washington Post reports that:

The Pentagon, expanding into the CIA’s historic bailiwick, has created a new espionage arm and is reinterpreting U.S. law to give Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld broad authority over clandestine operations abroad, according to interviews with participants and documents obtained by The Washington Post.

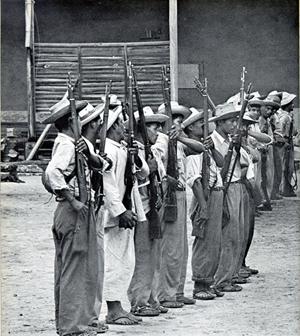

Our Friends in Guatemala, c. 1954.

The Pentagon promptly denied the report, but the Post’s reporting seems to confirm recent allegations that the Bush Administration is heavily employing covert operations, run through the Defense Department to evade congressional oversight.

Congress restricted covert operations for one excellent reason: Their track record is uniformly miserable, having done more damage to national security than not. Gregory Treverton, future Vice-Chairman of the National Intelligence Council, wrote in 1987 that “even the ‘successes’ of covert operations seem ambiguous or transient in retrospect, accomplished at significant cost to what we hold dear as a people and to America’s image in the world.”

Treverton’s judgement is based on the history of covert operations: every official review has suggested the United States use such operations less, not more. Here is a sample:

- In 1961, out-going President Eisenhower received a report from his board of intelligence advisors on CIA covert operations, including “successful” efforts to topple governments in Guatemala and Iran. Looking back at those efforts, the President’s Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities told Eisenhower that they had “been unable to conclude that, on balance, all of the covert action programs undertaken by CIA up to this time have been worth the risk or the great expenditure of manpower, money and other resources involved.” And those were the Agency’s salad days.

- The 1960s ushered in a decade of the CIA’s worst covert operations. Beginning with the tragedy at the Bay of Pigs, the CIA set new standards for outright weirdness with spectacularly unsuccessful attempts to kill or discredit Fidel Castro (check out the depilatory cigar story). This period ended with the CIA’s now well documented role in deposing the democractically elected government in Chile and an ensuing congressional investigation—the Church Committee. (Some conservatives blame Church for destroying the CIA, conveniently ignoring the role played by ostensibly “covert” operations that went awry in the most publicly ways.)

- During the 1980s, the Reagan Administration pursued a number of covert operations in Central America and the Middle East that converged in the Iran-Contra scandal.

The current restrictions, which the Bush Administration is dodging, resulted from the recommendations of the Tower Commission, empaneled in the wake of the Iran-Contra scandal. Congress incorporated the recommendations in The Intelligence Authorization Act of FY 1991. Title VI specifically addressed reporting requirements for covert operations:

The president must then make a written “finding” before beginning a covert action specifying that the operation is necessary to support an identifiable foreign policy objective and that it is important to U.S. national security. If Congress is not informed of the finding before the operation, the written finding must be transmitted in a timely manner to the relevant congressional committees, or to the bipartisan leadership of those committees. Title VI also imposes a limitation on the president’s war powers, that is, a presidential finding may not authorize any covert action that would violate the Constitution or any U.S. statutes.

Sounds reasonable. Bush 41, however, asserted Title VI unconstitutionally infringed on his right to withhold findings from Congress for unspecified periods of time—before the electorate constitutionally infringed on his right to be president. Clinton chose not to challenge the law, leaving us where we are now: Executive authority in foreign policy as stage setting for the weirdest Oedipal drama in the history of American politics.

Seriously, do you need another reason?

Perhaps, Congress should significantly restrict, or even ban, covert operations before somebody loses his eyes.

It is important to realize that covert operations do not include: activities to acquire intelligence, perform counterintelligence, improve or maintain the operational security of U.S. government programs, or carry out administrative activities. Covert operations also exclude traditional diplomatic, military, and law enforcement activities.

Rather, a covert action only refers to:

… an activity or activities of the United States Government to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad, where it is intended that the role of the United States Government will not be apparent or acknowledged publicly.

In other words, assistance to prop up our friends and topple our enemies that if disclosed—even after the operation is complete—would harm the national interest.

Should the United States undertake operations that, if disclosed, endanger national security? Rarely, if ever, for two reasons:

- First, covert operations are almost certain to be disclosed. Covert operations violate the first rule of life in Washington: Don’t ever do anything that you wouldn’t want to see on the front page of the Washington Post. The story by Bart Gellman helps drive the point home that, more often than not, covert operations eventually become public knowledge.

- Second, covert operations often fail because they are covert. Shielding programs from Congressional oversight allows for small programs to devolve into gigantic, often bizarre, schemes that would never pass muster with Congress. Writing about the Iran-Contra affair, Treverton warned of the danger from centralizing White House control over covert operations. “Excluding the designated congressional overseers,” Treverton wrote, “also excluded one more ‘political scrub,’ one more source of advice about what the American people would find acceptable.”

Given that the challenge posed by AlQaeda is, largely, an ideological bid for the hearts and minds of millions of Muslims perhaps one more political scrub might not be such a bad idea.

Update: CNN has sources confirming the existence of the unit at the center of the Post’s story. Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE) captured the essence of argument (2), noting that “the concern I always have in these matters as well as others when it comes to power in government is too much power concentrated in too few hands.” Hagel added, “That’s when a country gets into a lot of trouble, when you brush back the Congress and you don’t have oversight and you don’t have cooperation, and I see too much of that out of this Pentagon.”

Late Update: The New York Times weighs in with a we were scooped/mopping up article.

If it isn’t too obvious to mention … when we speak of how most covert operations become public … that would be only the ones we know about. By definition we don’t know about the ones that successfully remain covert, making any attempt to assess what percentage of them do or don’t remain secret kind of a guessing game…

People in other countries generally know when their government has been interfered with. Too often, we intervene on behalf of US interests, such as giant fruit companies. Our intervention keeps the fat cats happy and the third-world people impoverished, as well as provoking violence and terror.

Even if no one in the US found out, do we WANT more anti-Americanism in the world? Not to mention more violence, suffering and poverty? If we actually want to promote “Freedom”, “Liberty” and “Democracy” as the President SAYS we do, we need to respect other countries’ governments and interests—even if we have to add another quarter to the price of coffee at Starbucks.

Its difficult to add to the above posts, I’ll make an attempt. First, the old saying “whats done in the darkness will surely come to light..” may not always be true with covert ops, but as a rule I believe when we enter into immoral or amoral clandestine activity, it tears at the fabric of our nation. To me, its like condoning murder, as long as you don’t get caught. Call me naive, but when I see Old Glory, I don’t see any of this kind of hideous activity ( torture, murder, etc ) in what we are to aspire to. I also agree with Ms Lester, I’ll spend more for coffee or anything else when I know the workers are treated humanely and paid a decent wage. Either we are decent or we’re not, the time to decide is now.