Last fall I had the pleasure of going to the University of Hamburg at the invitation of the Research Group on Biological Arms Control to give a presentation on open source analysis for nonproliferation research. My colleagues there–Gunnar Jeremias, Mirko Himmel, Tomisha Bino, and Jakob Hersch–have been working on a very interesting project assessing Syria’s biological weapons capabilities. I think the wider community might be interested in this research, and when Gunnar suggested a guest post that other analysts might comment on, I happily agreed.

Spotlight on Syria’s biological weapons

By Gunnar Jeremias, Mirko Himmel, Tomisha Bino & Jakob Hersch

Research Group for Biological Arms Control, Center for Science and Peace Research, University of Hamburg, Germany

When talking about Syria’s bioweapon arsenal… Wait a minute. What? Wasn’t it all chemical? Indeed, more than two years after the chemical attacks on Ghouta in 2013, the subsequent entering of Syria into the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and more than a year after the destruction of Syria’s Sarin nerve agent stockpiles and its precursors under multilateral and multi-media supervision, chemical weapons are still an issue in Syria. Chlorine filled barrel bombs released from helicopters are frequently used as weapons of terror most probably by the Assad regime, and ISIS forces seem to have used mustard munitions.[1] This sad record is too large already, but it seems as if more entries have to be added: Not only are the doubts that Syria might not have declared its complete CW program expressed quite openly by many official sources – there are even hints that point to the presence of biological weapons in Syria, too. There was almost no reaction from the general public or the epistemic community when on 14 Jul 2014 Syria declared its ricin program. A declaration that included the existence of production facilities and stockpiles of purified ricin. Quite a number of documents by the UNSC and OPCW that have been made public touch upon this issue. However, the initial declaration was not made public.

There have been allegations of a Syrian bioweapons program for a long time now, although no details of a program have ever reached the public domain (not to mention information about the size and the level of sophistication (summarized in Cordesman, 2008) [2]. The first official notification that hinted towards a B-dimension in Syria’s armed forces was the statement of the former spokesman of the Syrian foreign ministry, Jihad Makdissi, made on 23 July 2012 that “No chemical or biological weapons will ever be used […] during the crisis in Syria no matter what the developments in Syria. All of these weapons are in storage and under security and the direct supervision of the Syrian military and will never be used unless Syria faces external aggression.”[3] While at that time one could still believe that Makdissi was mixing up biological and chemical weapons as it happens all the time the official Syrian declaration about the ricin program clearly changed things.

In the investigation of this case the first question that pops up clearly is: Why ricin? Ricin is a potent bio-toxin that can be isolated from the shell of castor beans and that can be lethal if, for example, ingested or inhaled. It is known in the public literature that in the past some states (e.g. the UK and the US) attempted to weaponize ricin for large scale attacks. Although these experiments date back to the 1940s there is still not much reason to believe that anytime anywhere in the world the problem of effective dissemination was solved. Hence, many experts think of ricin as a weapon of terror rather than a weapon of mass destruction. With the publicly available information, it is difficult at the moment to make any claims about the intention of the Syrian ricin program. Everything from assassination purposes via a proof-of-concept for successfully established methods to weaponize biological toxins to the contribution to the Syrian arsenal of unconventional weapons of deterrence are possible options.

Either way, the use of ricin as a weapon is strictly prohibited by both the CWC and the Biological and Toxins Weapons Convention (BWC). That the issue is dealt with under the CWC does by no means allow the conclusion that it should not be discussed as a bioweapon in the BWC context as well. Syria is a signatory state of the BWC since 1972, but has yet to ratify the treaty. However, it is possible to advance the view that also signatories of a treaty should not act in way that obviously violates its central obligations, and the production of ricin for non-peaceful purposes (e.g. in amounts that cannot be explained with medical dedications) would mark such a breach.

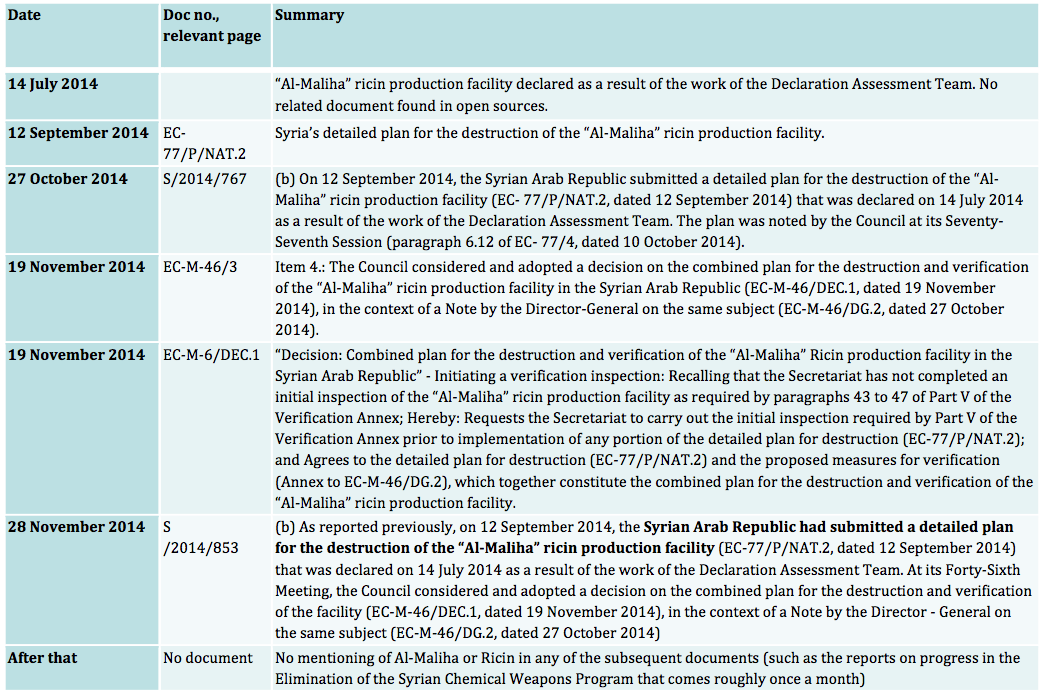

So, what do we know? Despite the frequent reporting by OPCW and UNSC from mid-2014 onwards, the public part of the story ends in November 2014 with quite a cliff-hanger: As a follow-up to the initial declaration on June 2014 a plan for destruction of the production facility was set up in September 2014 (EC- 77/P/NAT.2). Quite surprisingly for an external observer, it was only recognized in November that the site(s) of the program would be worth prior verification inspection (EC-M-6/DEC.1). Eventually the plan for destruction was decided along with the instruction that an OPCW team of experts should gather on the ground information to learn what exactly would have to be destroyed in the course of the disarmament activities (S/2014/853). And while one really gets excited about the progress of this story, since November 2014 there has only been a deafening silence on the issue. None of the monthly OPCW progress reports, nor any other public document mentioned the issue again. Even if it is somewhat likely that progress is hampered by the security situation on the ground, we would expect at least a notification that the process is delayed for good reasons. So:

What has happed to the ricin program?

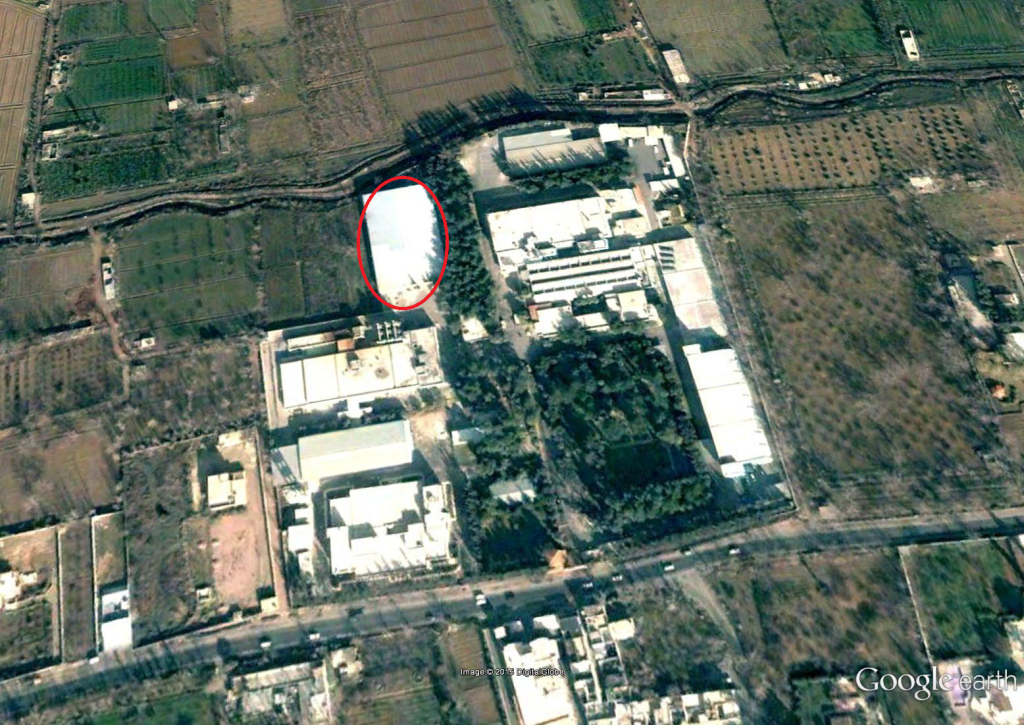

Anything else? Apart from the state of the program, there are, however, some more interesting issues that have been hinted to in the documents, which deserve some attention and which can be investigated further by the use of open source information. With astonishing openness OPCW speaks in the documents cited above of the “Al-Maliha ricin production facility” as the site where the program (at least in part) was located. Hence, the first and most driving question is: where exactly might this facility be located? Al-Maliha is an eastern suburb of Damascus. Given that the production facility is not underground (which is a possibility, though), there are basically three sites that can be considered. First, there is a military site.

Coordinates: 33°29’33.21’’N; 36°21’46.96’’E. Image taken on 8/15/2014.

Which, according to tags found in Wikimapia, is dedicated to the production of military garments.[4] Everybody can write comments and notes in Wikimapia, and we have trouble believing that Syrian uniforms really have to be protected with the kind of security perimeters that can be observed on the satellite imagery. But whatever they really do in that complex, the configuration of the buildings has nothing in common with biotechnological sites and/or pharmaceutical facilities in Syria and elsewhere in the world. Based on this gut feeling, we would say: This is not the site. The second candidate, a rubber factory, seems to be exactly what it is said to be.

Coordinates: 33°29’46.71’’N; 36°22’41.39’’E. Image taken on 5/5/2011.

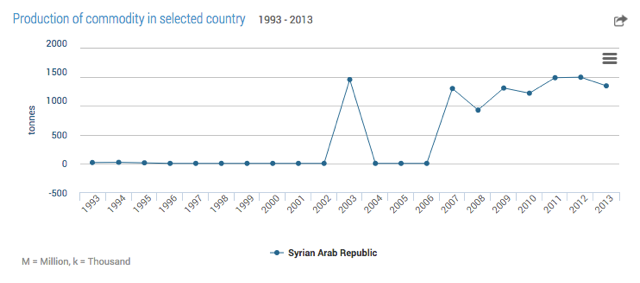

Although such company obviously must have some experience in the refinement of natural products, there are no reasons to believe that they do anything other than producing rubber. The neighboring facility is Tameco (“The Arab Medical Company”). And we would bet our bottom dollars that this is the “Al-Maliha ricin production facility”. Not only because this government owned factory is probably experienced in the handling of powders with sweeping effects, a further indicator is that construction work on the Tameco grounds was carried out at the same time when Syria started new agricultural activities: FAO reports that the production of castor beans in Syria in 2003 raised from a level just over zero to some 1.300 tons per year. It remained at this level even after the civil war began – in the years 2004-2006 there was possibly no reporting (in general there is not much to say against castor beans – their oil is used for many applications in industry and for cosmetics). [5]

Coordinates: 33°29’49.11’’N; 36°22’20.09’’E. Images taken on 03/30/2000 (image 1) and 12/24/2003 (image 2).

Today, after the Tameco facility has changed hands several times during the war, not much of the facility is left – it is literally bombed to ashes (image from 8/15/2014).

There is some footage available that shows some of the interior of the facility, before the destruction advanced to the actual level: the packages would most likely not contain ricin, so we won’t worry about that, but maybe some expert in bioprocess engineering could identify the equipment visible in the footage? [6] But of course all this does not tell us if the Assad regime was able to remove equipment required for ricin production to some other place before the bombardment – and we don’t know how much purified ricin really was produced and where it was (or still is) stored? Using open source information we were also not yet able to find the fields where the Castor trees were grown. It really bothers us that there still might be ricin stockpiles stored somewhere in Syria in such an unstable situation.

These are just the questions that pop up in regard to the ricin program. But history showed that countries that have decided to produce ricin for non-peaceful purposes (which, to stress that once again, is not yet verified for Syria!) have in many cases also developed a bioweapons program that was based on the (mis-)use of pathogens (mostly bacteria and viruses), too (e.g. Iraq). Are there any hints that the same happened in Syria? Indeed, the analysis of open source information at least allows for identifying some qualified questions in this regard, too. But that is another topic – possibly to be discussed here in the near future (if you Wonks would like to read more about it).

[1] http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/06/un-watchdog-confirms-mustard-gas-attack-in-syria

[2] http://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/080602_syrianwmd.pdf

[3] http://www.theweek.co.uk/middle-east/syria-uprising/48124/syria-chemical-weapons-warning-threat-or-reassurance

[4] http://wikimapia.org/#lang=de&lat=33.492676&lon=36.361423&z=19&m=b&show=/7008662/ar/%D9%85%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%88%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%A9&search=damascus

[5] http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/desktopdefault.aspx#ancor

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlQknSo5l7g; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEHI0PpVT1w

First off, thank you for sharing your research.

The portion of the facility you believe is the “Al-Maliha ricin production facility” is externally destroyed by, at the latest, 15 August 2014. This is visible on the given satellite imagery and also in the youtube video you linked in endnote 6. Yet as you note, the “detailed plan for the destruction of the “Al-Maliha” ricin production facility” (EC-77/P/NAT.2) is dated 12 September 2014, and the topic is discussed by the Council on 19 November 2014.

Unless you believe your candidate facility has an underground element that might have escaped unscathed, it is hard (at least for me) to reconcile the timelines of the facility destruction planning and of the candidate facility’s destruction. In other words, if your candidate facility really is the ricin production facility, why would there have been months of planning for its destruction after it had been ostensibly destroyed?

Overall, is there evidence that the “Al-Maliha ricin production facility” really is in the city of Al-Maliha? I ask because this would not be the first time that a facility is misleadingly named, or where several disparate sites share a common name.

Regards,

I agree this is an area that needs more attention and thank you for the post.

I would have to agree with Philippe. The videos don’t show any evidence of distillation equipment. What is shown appears to be tableting machines in various states of destruction. I hold a PhD in the Cell manufacturing for regenerative medicine. While not the in the area of expertise you are perhaps seeking for opinion I do feel i know enough about bioprocess equipment to say there is no obvious evidence on display that this is the facility you are seeking. I am open to being corrected on this.

I didn’t spot any evidence of containment hoods or air handling equipment that would be necessary to handle or assay any biologically created agents such as Ricin (safely) either. Although at a basic level you don’t need much in the way of equipment, a scaled operation as you suggest, would leave more of a footprint. As you point out this could have been removed earlier but I would have expected to at least see vents for any air handling system on the roof if their has been any safety concern factored into the facility design.

But… ricin isn’t a biological weapon, is it? It’s a chemical weapon (if derived from a biological source). I thought a biological weapon has to include a reproducing entity to fit the definition. Ricin is just a poison.

Oh. I read that the treaties include as biological weapons those “toxins” derived from a biological source. That is, in my very ignorant opinion, a bit dopey. It makes the distinction between biological and chemical weapons meaningless. Who cares what the source is? If I synthesise ricin by some non-biological process, that doesn’t make a lick of difference to what it is. If a we find a plant that can make trace amounts of mustard gas, it wouldn’t make a whole lot of sense to reclassify it as a biological agent.

Biological weapons that can replicate are, I would think, very clearly a completely different thing to poison, regardless of the source of that poison.

So I guess that’s why ricin didn’t get much attention. No-one but the treaty-reading public thinks ricin in a biological weapon.

🙂

Recall that it’s the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. Those toxins may have been better slipped into the CWC if we were sorting them by type, but then we’d have to try to figure out verification proceedures for them. Plus biological toxins tended to be folded into BW research.

The first two images & coordinates confused with each other!

Thank’s much for your replies. RAJ47: Yes, you are right. The first image belongs to the coordinates under the second image. Apologies!

On the issue if ricin is (in case of its weaponization) a biological weapon or a chemical weapon…well it’s both. There is a certain overlap of the agents covered by the two regimes marked by the biological toxins. The treaty to ban bioweapons is not by accident called “biological and toxin weapons convention”. Hence, ricin, saxotoxin etc. are covered by both treaties. Syria, however, has not ratified the BTWC. The case above might though be a reason to advocate for a full Syrain membership to the regime.

Now on the questions whether there is any evidence for the spotted site to be the declared one and if – should this be the case – there is anything left to be destroyed. I think that we have put together quite some indication that it is the site, but we wanted to make clear that proofs can only be produced on the ground. Which leads to the second question that touches the equipment and the building after its destruction. If OPCW speaks of verification and destruction this is not necessarily limited to the production buildings, but would include the production equipment and possible stockpiles, too. Of the latter two, we don’t know (given that this is the Al-Maliha ricin prioduction facility) if the government had the chance to remove them from the site before destruction. Mark, thank you very much for clarifying what kind of machinery can be seen in the footage. At least it tells us that this does not provide any further lead to the assumption that this might be the declared site. Since, weaponization of ricin seems to be an unsolved issue in larger parts, we have in any case no good idea what equipment could be expected apart from those for extraction and handling/packaging.

Our intention in putting together this piece was to raise awareness about the fact that the Syrian activities in chemical and at least rudimentary biological wepons development have more facets than sarin and chlorine.

Thanks for the response. I think this is an often overlooked area globally and you are right to draw attention to it. The potential for biological weapons proliferation is very high as the technological barriers to entry are comparatively low to nuclear proliferation and the equipment required is readily available and easy to move/hide for operations at a small scale. Ricin extraction is perhaps the most extreme example of this. Please continue your efforts – this is worthy effort and adds a new dimension to an excellent blog.

Nothing in the video to suggest anything other than formulation and packaging. But a <2 minute video is hardly conclusive. Interesting that the southern three bays of the facility have been struck with something significant – and possibly air delivered. So someone, with airpower, may have considered the building a worthwhile target.