Yesterday the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC) held a hearing on nuclear diplomacy with Iran. Speakers made several references to South Africa’s nuclear past and what it means for the six powers trying to negotiate a verification agreement with the Islamic Republic.

The IAEA and South Africa twenty years ago successfully resolved questions about South Africa’s former nuclear weapons activities. That record is resonating now among critics of the Iran/P5+1 process because Iran is currently challenging the IAEA’s authority to do the kind of verification the powers want to see included in a comprehensive agreement. But Iran won’t and can’t follow South Africa’s example without a fundamental rebooting of its relationship with the IAEA.

South Africa swung toward exceptional cooperation with the IAEA at a time when its strategic threat perception was changing and it was facing near-certain regime change. I suspect at least some of the critics who see South Africa as a model for Iran understand that and will draw their own conclusions. Neocons among them should be aware that the pressure which drove white supremacists to give up nuclear weapons was generated inside the country, not outside.

South Africa: The Record

Beginning in the 1970s, South Africa’s Apartheid regime, facing growing international isolation and conflict on its periphery, set up a secret program to develop and make nuclear weapons. By 1989 it produced six of these. In November 1989 it ordered the program terminated and by July 1991 South Africa dismantled its nuclear weapons. That same month it joined the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and negotiated a comprehensive safeguards agreement (CSA) which entered into force two months later. Only then did the IAEA obtain access to what was left of that program including, most importantly, the highly-enriched uranium used in the weapons. In less than two years, the IAEA had more or less accounted for all of South Africa’s declared nuclear materials. During this process involving about 150 inspections, the South African government never acknowledged or otherwise made known that it had secretly made nuclear weapons; the IAEA concerned itself with verifying the correctness and completeness of South Africa’s nuclear material inventory. The IAEA did not focus upon allegations of the kind of nuclear weapons activities which today suggest to the IAEA “possible military dimensions” (PMD) in Iran’s nuclear program.

In March 1993, South Africa declared that it had in the past made nuclear weapons. The IAEA then, also on the basis of extensive cooperation from South Africa, verified that all the nuclear material in the weapons program was accounted for and under safeguards, and that the nuclear weapons program was terminated.

The IAEA is confident that essential nuclear material-related activities in the nuclear weapons program are accounted for. It investigated PMD-type activities to the extent they were deemed critical to assure that at some future time South Africa would not re-constitute this program. It closed the books on this exercise in 2010.

No Change? No Cooperation

Some advocates of a robust verification arrangement for Iran under a comprehensive nuclear agreement now argue that South Africa’s extensive cooperation should be the standard for how Iran proceeds with the IAEA.

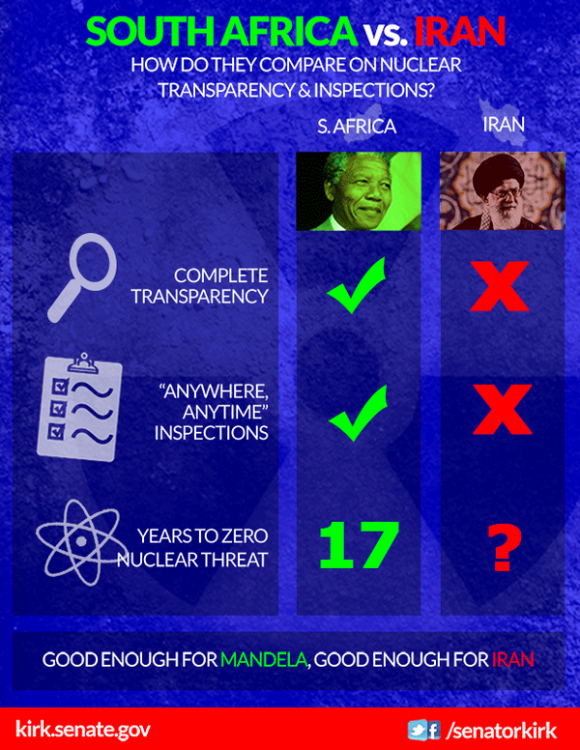

What was said on July 29 about South Africa by SFRC Chairman Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and by ex-IAEA safeguards director Olli Heinonen echoed a cyberspace exchange I had a few days before, in which Senator Menendez and also Senator Mark Kirk (R-IL) were linked in. On Twitter last week, Robert Zarate, a former Congressional staffer now here, put it this way to me: “S Africa decided 2 ‘come clean’ on nuke prog’s military dimensions. It’s the baseline 4 Iran.” Senator Kirk described what South Africa permitted the IAEA to do as “anywhere, anytime” inspections and he posted on Twitter a simple chart which checked boxes identifying South Africa as a poster child of transparency and Iran as a non-cooperator.

At the SFRC hearing a week later, a critical moment came when Menendez asked Heinonen “ Is a good model the South African model” which featured “unprecedented cooperation by allowing anywhere, anytime inspections?” Heinonen replied by qualifying that that approach “was successful [in South Africa because] that government had changed their view. They had given up their nuclear weapons program. They wanted to close that chapter.” But “if that change doesn’t take place in Iran,” he said, then effective verification is “going to be difficult as it was in North Korea” where the IAEA had extremely limited access under the 1994 Agreed Framework. Menendez concluded that the two cases were “very different… the two paradigms here, between where Iran is at and where South Africa is at.”

What are the Drivers?

What Heinonen didn’t say about South Africa’s re-evaluation of nuclear weapons is what others on the ground in South Africa have told me over the years that have elapsed since 1993–that the Apartheid state’s decisions from 1989 through 1993 to terminate the secret program and destroy its infrstructure were based upon a strategic calculation. That calculation ultimately expected that a black majority would in the near future take power, spearheaded by an African National Congress that ruling white supremacists did not want to see inherit a nuclear weapons arsenal or capability.

This version of events is decidedly not the official view of the ANC today, and since taking power it has formally embraced policies clearly in favor of disarmament and nonproliferation. But South African observers and witnesses then and now, white and black, have recalled to me again and again that at the end of the 1980s, the writing was on the wall. A process of internally-generated regime change in South Africa was a major driver of that country’s cooperation with the IAEA.

So Senator Kirk’s cyberspace broadside–that because transparency in South Africa was “good enough for Mandela” it should be “good enough for Iran”–won’t hold true so long as drivers for political change, such as those which made the difference in South Africa in the early 1990s, are not at work in Iran today. So long as the organizations and personalities who are determined to expand Iran’s sensitive nuclear activities are confident that they are invulnerable and enjoy the support of the leadership, it would not be wise to count upon Iran suddenly shifting gears and fully cooperating with the IAEA.

On June 14, six months after Iran and the six powers concluded the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA) setting up a roadmap for negotiation of a comprehensive agreement, Iran instead fundamentally challenged the IAEA’s authority to pursue PMD-related investigations, telling the IAEA in an official communication (Infcirc/866) that:

- the IAEA is not authorized to make requests for access based on United Nations Security Council or IAEA Board of Governors resolutions which are “politically motivated, illegal, and unjust”, and that

- the IAEA is not authorized or required to verify the completeness and correctness of states’ nuclear inventory declarations.

Regardless of the November 2013 Framework for Cooperation touted as the beginning of a reset in Iran’s relationship with the IAEA hand in hand with the conclusion of the JPOA, Iran’s positions concerning the IAEA’s verification mandate haven’t changed since 2005. The IAEA’s authority to pursue what the JPOA calls “past issues” in Iran however critically rests on those resolutions and upon support and endorsement by member states of its work including to assure that Iran’s declarations are complete and correct. In South Africa, verification of completeness and correctness was an essential component of the IAEA’s work to resolve questions about that country’s nuclear program–even before South Africa revealed that it had secretly made nuclear arms.

Mark, I feel confused after reading this post.

On the one hand, you point out that 1) the IAEA’s work in South Africa primarily involved “nuclear material-related activities”; & that 2) IAEA’s pursuit of PMD-type activities was not a thorough investigative enterprise for the sake of sketching a complete history of SA’s nuclear past, but concerned activities that were “critical” for making sure that SA won’t restart the program in the future.

This seems to imply that the IAEA should do something similar regarding Iran, i.e. focus primarily on “nuclear material-related” activities.

On the other hand, you imply that the only way for Iran “fully” to cooperate with the IAEA is to agree to anytime, anywhere inspections. Further, you imply that If Iran rejects such an inspections regime, it means their strategic objective is obtaining nuclear weapons.

I have another understanding of Iran’s possible motivations. Perhaps they have a completely different view of the IAEA than the Apartheid South African government did. Perhaps Iran believes that the West has used and will use the IAEA as a political tool in order to put undue pressure on Iran. Perhaps Iranian leaders fear that unlike in South Africa, the IAEA will go on a never-ending witch-hunt in Iran in order to ensure Iran’s nuclear file won’t come back from the UNSC & therefore ensure restrictions would remain in place even after the deal expires. And perhaps they think, under these circumstances, that accepting anytime, anywhere inspections would seriously compromise their national security.

In other words, perhaps Iran’s motivations for rejecting anywhere, anytime inspections have nothing to do with nuclear weapons, and more to do with their suspicion that the IAEA is not a professional, impartial organization.

Does this make any sense?

Mark, the South Africa parallel is also interesting in other ways. (1) The SA bomb was mostly to ensure a paranoid’s regime security in light of the perceived Soviet/Cuban threat; there was harldy any “prestige” dimension. (In Iran, the program did not stop when its original security rationale – the Iraqi threat – disappeared; the weaponization work was merely “halted”/dispersed for other reasons.) (2) Sanctions against SA contributed to some extent to the forced evolution of the regime. (Iran, however, is less isolated in 2014 that SA was in 1988.)

Rene,

You say:

On the other hand, you imply that the only way for Iran “fully” to cooperate with the IAEA is to agree to anytime, anywhere inspections. Further, you imply that If Iran rejects such an inspections regime, it means their strategic objective is obtaining nuclear weapons.

No, I am not implying that this is the “only way for Iran to ‘fully’ cooperate with the IAEA.

I am saying less than that. I’m saying that if people want Iran to do what South Africa did in the way of affording transparency, that won’t happen unless Iran fundamentally changes its relationship with the IAEA. Right now, Iran disputes that the IAEA has the authority to do in Iran what it did in South Africa unless Iran will agree to that voluntarily which it has not agreed to.

The reasons you give for Iranian refusal to accede to the IAEA’s request for access are in fact things that Iran has said to the Board of Governors and to the IAEA Secretariat on numerous occasions.

Iran and South African cases are different from a number of standpoints which I didn’t get into in the interest of keeping the post shorter than it could have been. One of those differences is that when South Africa afforded the IAEA wide-ranging access, it had already given up its nuclear weapons infrastructure. The government made a decision that giving it up and declaring all of it would be of greater benefit than keeping it secret and having nuclear weapons. As I said South Africans tell me that calculus was driven in part by the aim of the white supremacist government to keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of a black majority government led by the ANC. In the case of Iran, the situation is totally different. Iran’s behavior in the negotiations with the powers is to try to preserve as many of its nuclear assets as possible in a deal that lifts all the nuclear sanctions. Iran sees its nuclear program as something that gives Iran status, bargaining power, diplomatic leverage, and, also, the possibility of using the technology to generate electricity and other peaceful benefits, and possibly a hedge for future nuclear arms. In this situation, the more opaque Iran’s nuclear program is, the more status, leverage, bargaining power, etc. Iran has. How many times has the SL told his audiences that Qaddafi made a mistake in giving up his nuclear assets away to the West?

It isn’t clear to me that Iran’s leaders have concluded that being transparent–in the sense that South Africa was transparent–is on balance in Iran’s interest.

But by no means do I imply, as you say I do, that “if Iran rejects [a South African-type] inspections regime, it means their strategic objective is obtaining nuclear weapons.”

One of the problems in the Iran conundrum for outsiders looking in (that includes the IAEA and its member states) is that there is no consensus about what the strategic objectives of Iran’s nuclear program are.

Mark: you should not necessarily assume that the Iranians know what they want. By that I mean that the most likely explanation of their behavior over the past 12 years is that various centers of power do not want the same thing, and that some of them may have changed their mind over exactly what the ultimate goal of the program should be. (Of course, we both know some people in DC and elsewhere who think that the SL has always known what he wanted and that is the Bomb, but even if true that should not prevent us from refining the analysis of the political dynamics in Tehran.)

Shaheen, agreed it is a complex picture. That’s one of the problems in P5+1/Iran talks, i.e., the Zarif group at the table is speaking for whom, exactly, back in Tehran? But ultimately if the negotiators agree on a text, the government of Iran will have to make a choice, someone will in the final analysis make a decision. A no-decision result in Tehran would be perhaps along the lines you imply.

Thank you for your response, Mark. You make a very interesting point by saying that “the more opaque Iran’s nuclear program is, the more status, leverage, bargaining power, etc. Iran has.”

But just how opaque is Iran’s program when their centrifuge inventories & assembly workshops & rotor-manufacturing workshops are known by the IAEA? When the minimum bar for transparency in the comprehensive agreement is the AP? Can Iran maintain any meaningful degree of “strategic opaqueness” under these conditions?

In other words, I think Iran has already bit the bullet of transparency to the extent that its important nuclear assets are well-known and therefore vulnerable. Does it make a meaningful contribution to their nuclear-related goals if they resist inspections of their suspected military sites? If yes, then I would agree with you. If not, the opaqueness in the latter domain might have other drivers.

I think the country that indeed draws some benefit from opaqueness is North Korea, and when I compare that program to Iran’s, I feel that Iran’s program is quite transparent.

Rene,

Lest we forget, as of now Iran has yet to make a commitment to the kind of transparency measures you mention. That includes the AP, which is not being implemented. The commitments which Iran has made in the JPOA are temporary, that includes the monitoring of Iran’s centrifuge production infrastructure which you mention.

So Iran has yet to decide whether it will exchange these commitments–which will reduce opacity and uncertainties–for sanctions relief. It comes down to this: What will the Iranian leadership decide is ultimately in Iran’s best interest and higher priority: having a nuclear program with fewer limitations, or reaping the benefit of lifting sanctions.

North Korea is out of the treaty. There are no inspections. That’s not a yardstick for judging how transparent Iran’s program is. A better yardstick would be countries with sensitive fuel cycle capabilities which are implementing their AP, Code 3.1, etc. without the constant needling and challenging of the IAEA which we have seen from Iran since 2003 (look at Infcirc/866 for example linked in the post) and without Iran’s 18-year track record of violations of its safeguards obligations.

Mark,

According to the JPoA, comprehensive lifting of sanctions doesn’t come without Iran implementing the AP. So I think Iranian leaders have already decided that it _is_ in Iran’s interest to be more transparent in order to have the sanctions lifted. Judging by the news, transparency is not a major sticking point in the talks; the size & scope of Iran’s enrichment program is. Your comments seem to conflate these two issues when they move seamlessly from “reduc[ing] opacity” to the issue of “limitations.”

I wasn’t suggesting that North Korea should be used as a benchmark for judging Iran. I meant that if a country wants really to benefit from opaqueness, they need to be really opaque, like North Korea. Otherwise, with the kind of inspections going on in Iran (which will increase if a comprehensive deal is reached), I see little meaningful opaqueness-based benefit.

Rene,

I beg to differ.

The JPOA is an agreement to do things for a limited period of time. Six months, and now an additional four months. Iran’s commitments which it is implementing now are reversable. If they decide in four months that the P5+1 are demanding limitations on their nuclear program which are unacceptable, the deal’s off and the default position is where they were before November 24. So I would not agree that “Iran has already decided” in favor of the transparency-for-sanctions-relief outcome. They have agreed to test this. They haven’t made a final decision on any of this. Neither has the other side. Both sides have agreed to the diplomatic process but resolution will depend specifically on what’s in the final draft agreement.

In any event the ultimate decision for Iran would be made by the Iranian leadership in Tehran–not by Zarif and his negotiators. Same goes for the P5+1. This week Iranian news outlets reported that Iranian lawmakers will be getting more involved in the process; that is being interpreted widely as a sign that hardliners who are critical of any deal to make concessions are on the rise, matching their counterparts in the U.S. Congress.

Any of the items in the basket of things that Iran has not agreed to do until the negotiations resulted in the JPOA and the Framework for Cooperation last November I would broadly characterize as limitations on Iran’s freedom of action. These are things that Iran would see as concessions in exchange for sanctions relief. That list includes resolution of “past issues” which gets us in to the transparency issue. Since 2009 Iran has declared this body of evidence to be fabricated and it has not addressed specific allegations. Iran will have to address them to lift sanctions in a comprehensive agreement. News reports suggest that Iran and the IAEA are not on the same page, and that Iran is not moving forward to the IAEA’s satisfaction. There are a panoply of issues that are unresolved in the talks between Iran and the powers. The centrifuge numbers issues made headlines in June and July but it is by no means the only thing where there are differences.

I tend to agree with much of what Mark is saying about important differences characterizing situations in South Africa in 1980s-1990s and Iran today., which make it unreasonable to expect and counterproductive to argue that South Africa’s precedent should be applied to Iran as far as dismantlement of nuclear weapons program, disclosures and verification by the IAEA are concerned. But I would add also that South Africa under the apartheid regime did have a rather successful nuclear weapons program and was ready to test in 1977; there were little doubts about that in the Soviet foreign policy and security establishments, and, as far as I understood it at that time, in the US as well. The same can’t be said about Iran today (despite some possible, not yet well understood, but clearly limited experiments more than 10 years ago; several latest NIEs (which do not differ much from Russian assessments) attest to that. Thus, it’s a huge methodological and political mistake to demand that Iran dismantles what it does not have.

As Mark correctly notes, the decision to come clean on nuclear weapons, which triggered all subsequent activities, was taken by more forward looking members of the then South Africa’s apartheid leadership, who understood the inevitability of majority rule. This was the political basis for everything else including unprecedented verification (and, by the way, there were some difficulties with that as well, even under the new ANC-led government). This simply not applicable to Iran. In theory, there could be other equally compelling political considerations capable of convincing Iran to accept such verification – duly verified dismantlement of Israeli nuclear weapons program, for example, but I do not think the proponents of applying South African precedent to Iran can consider that.

Serguei: I don’t think the Israel argument is relevant. There is no evidence that Iranian military intentions were motivated by Israel’s nuclear weapons. And in the public arena, it would be hard for the Iranians to justify the abandonment of the NW option (which is not supposed to exist) by a hypothetical Israeli abandonment of their own NW.

Sergei,

Yes, another one of the differences between Iran and South Africa is that South Africa already had nuclear weapons (see my remarks to Rene above on this). The fact that South Africa aimed to destroy its weapons and infrastructure meant in practice that there was effectively no difference in South Africa’s willingness to cooperate with the IAEA in assuring completeness and correctness either in 1991 (when South Africa acceded to the NPT) or in 1993 (when it admitted it had nuclear weapons).

The difference between 1991 and 1993 was a matter of degree of intrusion, where PMD-type questions played a limited role prior to the 1993 admission and more of a role for obvious reasons (including C&C concerns) from 1993 onward.

That said, it is instructive what you say about what the USSR knew then.

I was in Moscow several times during the period between 1991 and 1993 while working as a journalist in those times. I found Soviet official sources who were willing to discuss with me some matters about which the USSR knew concerning South Africa’s preparations for testing and weaponization-related R&D and about other materials which I don’t want to discuss here in detail. But the USSR clearly knew a lot about certain aspects of that weapons program, Soviet intelligence had penetrated parts of it, and–about this I am certain–some information was shared with the IAEA to the extent that the USSR considered that to be appropriate and prudent. What a difference in the present situation in Vienna! The very early 1990s–those were the good times in US-Soviet relations on nuclear weapons, and the IAEA’s investigation of the program in South Africa benefited from that collaboration. My nostalgia for that particular “window of opportunity” is great.

It is a shame that the Israeli dimension of the Iran negotiation never materialized in the direction you relate. I wonder whether Iran is seriously concerned about Israeli possession of nuclear weapons to the extent that Iran would feel better off without Israeli nuclear weapons than with them. But it is a moot point because in the present environment in the region, there is no chance of getting an Israeli-Iranian buy-in on disarmament that could benefit the P5+1/Iran negotiation, in my view. There is just too much poison in the air. And too many rockets and too many airstrikes.

The “PMD” claims about Iran have no basis and thus far after more than a DECADE of investigation, none of it has been verified and instead quite a bit of it turned out to be fraudulent, including the “AP Graph”.

In comparing S Africa to Iran you’re overlooking the fact that there were legitimate indications that S Africa was making nukes (including Israeli efforts to sell them nukes) whereas no such thing is true in the case of Iran, and furthermore the ‘transparency measures’ that the IAEA demanded of were — according to the IAEA itelf — beyond what the NPT or the Additional Protocol (to which Iran is nto a party) would have required. Furthermore to say that iran is not transparent is utter nonsense: Iran suspended enrichment entirely, allowed repeated inspections of military bases well in excess of the NPT or the Additional Protocol based on NOTHING more than a collection of innuendo promoted in the media by motivated groups, and finally, the IAEA has repeatedly stated that it has no evidence of a nuclear weapons program in iran, EVER.

The South African/Afrikanner fear of a Soviet-Cuban invasion might be what some may have thought, but in a discussion with a South African professor of political science at the IISS conference in Oxford back in 1998, he said to me that they built their six weapons to counter the “black horde” they thought would be invading them. He didn’t quite put it this way (because he was a very decent fellow), but his implication was that, now that the black hordes were taking over the governance of South Africa, it was better that those guys not have nuclear weapons.