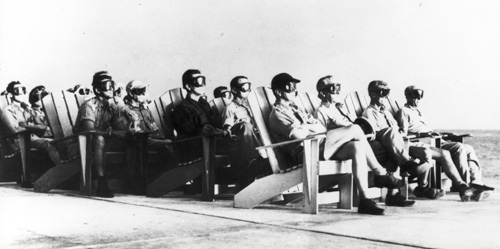

VIP observers on Parry Island, watching an 81 kiloton test as part of Operation Greenhouse, on Enewetak Atoll, April 8, 1951. Credit: Brookings Institution/Defense Special Weapons Agency

At the end of my discussion of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty with Linton Brooks, he suggested that I interview someone who’s a “treaty skeptic”, who has doubts about the treaty and is able to explain them well. He referred me to Tom Scheber, who is Vice President of the National Institute for Public Policy. You can read Mr. Scheber’s biographical statement here, which includes a description of his academic and military background as well as what he did at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL).

I feel that listening to the arguments of rational CTBT skeptics is important whether or not you agree with them, because it will give you an idea of what we’ll see once the discussion gets going among Senators. As Daryl Kimball said about Senate prospects for approval of the resolution of ratification, “…in the Senate we’re at the beginning of a treaty engagement and education process that could take quite some time.”

As with the previous two interviews, my questions are in italic boldface; Mr. Scheber’s replies follow. I have inserted hyperlinks as references wherever they might be needed.

Mr. Scheber was quick to point out to me that although he was part of the technical staff at LANL from 1989 through 2000, he is not a weapons designer; his masters degree in operations research is why he joined the LANL staff, where he “worked in weapon studies and concepts doing operational effectiveness analyses…”.

Despite the fact that he’s a treaty skeptic, it’s important to remember that his opinion of the CTBT is based on some very solid experience in the nuclear weapons complex.

As much as you can without breaching any classification rules, can you tell me a little more about what you did when you worked at LANL and for the DoE, and your general experience in that environment?

… [It] was a very dynamic time, because ’90 to 2000, which was when I was in the nuclear weapons technology directorate spanned the time frame from continuing to develop a wide portfolio of weapons, test them in Nevada, nuclear-driven directed energy concepts, until the dissolution of the Soviet Union and our change in plans following that, the test moratorium and the plans for the CTBT, and then I was very actively involved in the planning for stockpile life extension programs, and the stockpile stewardship program. So, I was using my military background and my technical background, but not as a weapons physicist.

I worked in the nuclear weapons technology directorate and had a change to interface with a wide variety of technical people. My background gave me at least enough insight that I understood what they were doing, what they trying to accomplish, and some of the issues, and then I helped to roll those issue together into our program plans.

Many things have changed since 1999. There have been some recent State Department officials’ speeches about the CTBT, indicating that the Obama administration is clearly opening the doors to start discussing the treaty again, against the backdrop of a greatly expanded nuclear complex budget. Also, it has been well-established that data from JASON show the stockpile maintenance and LEP programs are working.

But you still have your doubts about the CTBT, even though many people are convinced the bombs will work and things will be fine for a long time.

So, I have three big questions that are a significant part of the picture when it comes to differences of opinions between CTBT skeptics and CTBT proponents:

- How the treaty defines a nuclear test

- How verifiable and enforceable the treaty is, and

- The effect of US ratification of the treaty on our politics, agenda, and that of the rest of the world.

Let’s start by talking about Article I of the treaty, which states, in part:

Each State Party undertakes not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion, and to prohibit and prevent any such nuclear explosion at any place under its jurisdiction or control.

It’s my understanding that for treaty proponents, Article I is perfectly clear: “zero means zero”, i.e. that the treaty clearly bans all nuclear tests, period. It’s also my perception that treaty skeptics and opponents feel that Article I was not clear at all on what constituted a nuclear test, and left a lot open to interpretation. Since you have your doubts about the CTBT, perhaps you could go into some detail about your thoughts regarding Article I.

[The CTBT] was negotiated in the Conference on Disarmament, where every country — it’s a consensus group, and every country essentially has a veto vote, and so that is why the CTBT that we have looks like it does. It is the least common denominator that all of the countries could agree to, and so we do not have a definition for a nuclear test.

And when queried by the Senate, the State Department responded — it was questioned on whether there were any side agreements on the definition of a nuclear test. Our Ambassador Ledogar, who negotiated the treaty claimed there was at least a verbal understanding. The State Department said they have no record of any such side agreement or definition.

So it’s a key issue. That is the single most important issue associated with the CTBT, of what is it that is to be prevented or constrained. So, we certainly talked to several of our Russian colleagues through the years, who verified that Russia has a different way of interpreting the ‘no nuclear tests’ than we do, there’s nothing official that they’ve been willing to put in print, and so the lack of a definition becomes key.

[Additionally, the CTBT], with all its flaws, is of indefinite duration, and so this goes on without end, if it ever enters into force, and until it is either abrogated or we discontinue it.

I’d like to pursue the concept of “zero” further. Could you explain why you feel there is more nuance than simply “zero means zero”, and why you feel it is technically difficult to define “zero”?

Trying to decide and precisely define what “zero” means is very technically difficult. The United States has a working definition that as long as the weapon remains subcritical, and does not exceed criticality, in a test, that that is our definition of “zero”. And of course even with that, there is a very small energy release, but other nations, it’s not clear that they abide by the same kind of working definition. In fact I think if you look at the Strategic Posture Commission Report of two years ago, the consensus view was that Russia has apparently not abided by the same restrictive definition and their wording is, has apparently conducted nuclear tests. That’s the wording that they agree to use in the unclassified document, and the commissioners looked at the classified record to arrive at that finding.

Regardless of how one defines a nuclear test, the treaty must lay out a framework for detection and verification of nuclear tests, and subsequent enforcement of the treaty. Technology is very different from what it was when the treaty was defeated in the US Senate, eleven years ago. Based upon those technical improvements, do you the the treaty is verifiable? If so, how?

I think you’re getting at a key point, and I’m another person who likes to kind of dig down into the issues, and when you ask, is it verifiable, what does ‘verification’ mean, what would verification entail — in many of the discussions, there is a blurring of the definition that ‘something has happened’ that needs to be verified and needs to be investigated, and the term “verifiability”.

I’ve been in… briefings where the seismologists show charts, and they show different kinds of mine explosions, and nuclear explosions, and signatures [that go with them]. But at the very low level, the ability to take information that is provided by the International Monitoring System [IMS, see treaty protocol] and sort through and precisely determine what has happened and where it’s happened is — the lower the yield and the smaller the explosion, given all the Earth’s other background noise and events going on is very difficult.

And so I think where the International Monitoring System is very helpful is at detecting that an event has occurred somewhere and that needs to be verified, and I think that’s a good thing — the participation and the development of the IMF is helpful in instilling some level of confidence. At the same time, the treaty itself is so weak that I’m not very hopeful that the detection of an event would then yield to a timely and accurate inspection. First, the delay, and each country has to provide their own assessment of the convening of this executive commission to debate whether an inspection is required, the time required to assemble a team, and all that time, evidence is degrading that would help determine precisely what happened, and as well as the cooperation of a country who has to cooperate with the inspection, and they might refuse to be inspected or to let a particular area be inspected.

And as you know, the treaty allows for some small areas to be declared off-limits, and not inspected also.

Given the scenario in which treaty signatories all manage to agree that there has been a nuclear test, and then assemble an inspection team, do you think the politics behind the scenes could be as complex as it sounded, especially with some countries possibly backing the country that tested the weapon?

…[J]ust as in the UNGA or other commissions on the United Nations, that there will be bargaining and horse-trading behind the scenes… there’s very complex issues at work here which I think undermine some of the purported benefits that CTBT advocates would claim will happen if we ratify the treaty.

Going back to the subject of advanced technology and verification, could you go into a little more detail about the IMS? Are all countries deploying it equally well?

You know, I think on many of these issues, the US has gone the extra mile. I know other countries will criticize us because we haven’t ratified the CTBT, and for other actions, they’ll be critical of the US. But even on certain aspects of the CTBT, such as the placement of seismic sensors and stations around the world, we have gone the extra mile.

Russia, and China in particular, neither one of them has been willing to place an IMS station — within Russia, the nearest station is over a thousand kilometers from the test site at Novaya Zemlya. In China the nearest station is over 750 kilometers away [from their test site, Lop Nur]. However, in the US, we have three IMS stations within 500 kilometers — one is closest, 250 kilometers of our test site. Now, the seismologists have explained that there’s a rationale for that involving different kinds of soil, but it shows a lack of good faith at least by Russia and China. If you look at where all these stations are positioned, in particular it’s easiest to see on a map of China; there’s this big “hole” in the middle of China. And you ask, well, what’s in the middle of that hole? And that’s Lop Nur!

I think Russian has been more dependent on variant low yield nuclear tests and experience with them than we have. They have developed — and there’s a lot written about it — these triple containment vessels [Kolbas] to contain explosives and even very low-yield nuclear tests that would even contain any gases from escaping. They’re made to be resilient, to expand. Their literature says that they have been cemented in underground locations at their test site at Novaya Zemlya…

… [T]hey’re very innovative, and so it’s clear to me from seeing the kinds of money that the Russians have poured into revitalizing Novaya Zemlya that the experiments that are conducted up there are very valuable to them, that they really don’t want us to know much about what’s going on. If you’re going to go and conduct experiments above the Arctic Circle, [where] you can only work for parts of the year. It’s a very costly way of doing business, so this must provide something of significant value for the Russians and their nuclear weapons program.

[Scheber specifically mentioned the recent NIPP report on the CTBT, in which, the Kolbas are mentioned as a particular concern in the context of Russia conducting any “nuclear tests”, in the same context as such tests were discussed in the 2009 Strategic Posture Commission.]

My next question for you is literally a global question regarding the United States versus the rest of the world, with the CTBT as a backdrop. How do you feel about the treaty in the context of US global security and foreign policy?

Let me just quickly get to where I think the most serious issue is.

The outline is this. It is that for the US, either nuclear weapons remain important to the security of our country and its allies, or they don’t. I think some people will claim that yes, they’re important, but when you push them and really ask them what they believe about the subject, I find that they don’t really believe they’re of much importance. I think in the long term… all national security documents indicate that they’re still important, and you have to question the individuals to see if they believe that or not, but I tend to believe that they remain important for us, and they certainly are of importance to our allies.

So if they’re important for our security and allies’ security, then it is a national priority to ensure that those nuclear warheads and the weapons have high reliability. They seem to go together, and I don’t know how you can separate them.Now, the question is, what does the test ban have to do with that?

One: the US did not prepare for a nuclear test ban environment. The moratorium on testing was thrust upon the nuclear weapons design community, there was a half-hearted effort to prepare, but we were not like other countries such as France, and I think the French probably, in retrospect, did it the right way. When there was a sustained effort to negotiate a test ban treaty — flawed as it was, the French continued testing, and they worked to design, test, validate, and collect data on computer codes for a couple of new warhead designs, which they have since built and fielded, and which they were specifically intended to be be able to be maintained, hopefully, without testing… the French went forward, they tested it, they got data on those designs; once that design and test series was complete — actually they had one more test if they needed they planned to do and they indicated that they did not need that. And then once it was complete [the series], they ratified the CTBT. I think the French took a prudent approach in their design.

The US, if you follow the historic record, it was the cutoff in appropriation funding at the end of September ’92, the end of FY92, and the reestablishment of funding was to be contingent on a presidentially submitted, three-year test program, which would focus on improved security and safety devices for nuclear warheads which could be sustained for the long term without testing. Well, that three-year test series was never conducted, President George H.W. Bush developed a plan [see Section 1.6 here], but when President William Clinton came in in January 1993, he indicated there would be no testing, and the CTBT and the US moratorium for that is history.

Here’s my final question: what do you think was the end result of that situation? Could the US be confident that it could rely upon its nuclear weapons to do the job, if it came to that? Was the stockpile prepared for a testing moratorium?

I do think the Stockpile Stewardship Program — and I was at Los Alamos when it was initially called the Science-Based Stockpile Stewardship — is doing some very good things, but at best it can provide a lesser standard than testing. I think the United States has probably the most technically sophisticated and complex warheads in the world, and it’s sort of like having a very sophisticated car in your driveway that you haven’t started for 20 years. Stockpile stewardship — if I can equate it to that — I would assert it is a lesser standard than that provided by testing, and I’ll explain that.

Stockpile stewardship is the calculations, and the experiments, that, at best, tell you there is an absence of evidence that the warheads will not work. They’ll say there’s no reason why these should not work. It’s like your car being in the driveway, and on on a cold morning, someone going out and having done a variety of checks, and saying ‘there’s no reason why this car shouldn’t start’.

Now, the question is, will it start? Testing provides evidence that warheads either do work or do not, or work partially. And so stockpile stewardship can tell you that there’s no evidence that the warheads will not work. That’s essentially what the current certification process performs. They look at the available data, assess whether there is any significant change or degradation which would interfere with the proper functioning of the warhead, and then the lab directors have a judgement to make whether they can certify that that warhead would work consistent with the specifications that have been provided.

It is a lesser standard than periodically conducting a nuclear test to provide evidence that, in fact, they do work.

And so, I am not of the community that says we should immediately conduct nuclear tests. But because [nuclear weapons] are of paramount importance to the United States and its allies, because we did not prepare for a test ban, and because the reliability is extremely important, that we should retain the option to test in the future, and therefore we should not lock ourselves in by ratifying the CTBT, which would then force us to go through the painful, legal processes of giving notification and withdrawing from the treaty if that ever is needed in the future.

I expect this interview will lead to a rather animated discussion. What do you think of Mr. Scheber’s points?

I agree in the long run, and it really is a question of timescale. I do not believe anyone has real doubts that if the United States were called upon to conduct a nuclear (counter)attack tomorrow, most of the weapons would work approximately as intended. At the other extreme, if the current geopolitical circumstances persist until say 10,000 AD, I do not believe that anyone would consider the US nuclear arsenal to be an effective deterrent based on a test series more than eight thousand years in the past. Sometime between now and then, and rather closer to now, it will be necessary to either abandon nuclear deterrence or conduct additional tests.

I agree with Mr. Scheber that where we are now is not optimal. If the United States had entered the CTBT era with a properly-planned series of tests focused on the stockpile stewardship issue, we might be on solid ground for the remainder of this century; as is I suspect new testing will be required by 2050. I can probably be convinced to shift those dates a few decades in either direction. But, short of Global Zero, there will eventually be a requirement for new tests.

Note also that this requirement is as much diplomatic as technical. If a nation refrains from testing for so long that most observers suspect its nuclear arsenal has rusted into uselessness, it will also be suspected that this nation suffers an aversion to detonating nuclear weapons that is so severe it wouldn’t ever use them even if they did work.

So the question comes down to, how likely is it that we will achieve Global Zero (or some other stable equilibrium not including nuclear deterrence), before ~2050? And, how important is the CTBT to that process?

Scheber, and myself, seem to be nonproliferation pessimists. Scheber further argues that the CTBT isn’t even that helpful for nonproliferation on the grounds that it is too easy to cheat. I’m not sure I agree with him on that last point, so I do think that the CTBT may be useful in the short term. Preferably with a clear understanding of the circumstances – including “it’s been X years and we still haven’t made any progress on general disarmament” – that would lead to withdrawl.

And yes, the CTBT would be more useful still with some more precise language, better verification, and a better final US (and British, maybe Russian) test series, but those aren’t going to happen. The CTBT is, for now, what we have available.

John, is your belief that new testing would be needed in 10,000 years or even in 40 years stem from your concern that the laws of physics will change in that time period, or due to a possible regression of human (or American) technical capabilities which might render us unable to reproduce the nuclear weapons and manufacturing processes to the legacy design specifications which were used to produce them in the past? Do you expect the growth coefficient of Moore’s law to change sign over the next few decades, so that our computers become less able to simulate nuclear detonations down to the last blip? Or do you expect our abilities in machining, micromachining, materials science, or some other capability fundamental to the production of nuclear weapons as practiced in the 1940s-1980s to regress? Or is it just that possibly other actors may assess that US capabilities have deteriorated to such a degree that we are no longer able to reproduce the weapons of a half-century (or millennia) past?

I expect new testing will be required (i.e. that both the actual and percieved reliability of the US nuclear stockpile will asymptotically approach zero without testing) because the actual specific nuclear weapons that currently exist will degrade over time and because attempts to build new or refurbish old devices to exactly the same specifications as the original will fail as those specifications become as obscure as, say, Genesis 6:14-16.

The timescale is legitimately debatable. But I have personally seen space hardware that has worked reliably for thirty years, fail when a shift to a new subcontractor resulted in parts that were a precise dimensional and material match for the original drawings yet didn’t work. The rule in aerospace is, when you shift to a new supplier or a new facility, you do a proof test, and that isn’t paranoia.

No changes in the laws of physics are needed, nor any degradation of American technical capabilities. American technical capabilities are, as you know perfectly well, fall somewhat short of metaphysical perfection. Every time we tell a new generation of weaponeers, “This is absolutely everything you need to know to keep the bombs working”, we will leave some details out and get others wrong.

I am perfectly willing to believe that if we were very careful in our preparations, we could coast for a century on the basis of past achievement. Not a millenium. And probably not a century if we didn’t prepare properly, which Scheber claims is the case.

John, as you write below, “Testing as conducted by the United States prior to 1992 was not intended to statistically validate specific weapons designs, but to validate the design process.” You can’t have it both ways. If warhead reliability was always based on inspection and assessment of the physical condition of warheads to determine their conformity with the specifications of proven design, then there is no reason their validation on that basis cannot continue indefinitely.

As for your somewhat mysterious assertion that you have seen “parts that were a precise dimensional and material match for the original drawings yet didn’t work”, that obviously can result only from the specifications having been incomplete, and probably to a lower standard, relative to requirements, than would be the case for nuclear warheads.

Anyone who expects the republicans (or even all democrats) to vote for the CTBT should stop smoking that stuff.

The CTBT is a dead issue. It has been for over a decade.

As for testing, who knows? During much of it’s service life the W-47 was not a good prospect for functioning as intended. It was quite effective as a deterrent because it could work and who wanted to bet it wouldn’t?

On the contrary, it’s been repeatedly discussed over the past 10 years. And there would be a number of Democrats who’d vote for it; however, there would be far fewer Republicans, even with Jon “Let’s start testing again” Kyl not there to play his role as Minister of Misinformation.

Think about what Linton Brooks said in my previous post. The political barrier to testing is so high that it’s a pipe dream to even think of proposing it.

If the CTBT does ever pass, it’ll be because some sort of bargain is struck, a thought that is laid out quite well here.

“It was quite effective as a deterrent because it could work and who wanted to bet…” This betrays the silliness of questioning “reliability” to begin with. It is typically claimed that an “unreliable” warhead is not an effective deterrent. Thank you Mark for showing us the light. I’m glad testing will be unnecessary, and that we should proceed in ratifying the treaty.

Dr. Scheber may be correct from his perspective and limited range of experience, but as Herb York put it the problem is “exaggerated by a widely held myth: that technical experts – generals, scientists, strategic analysts – have some special knowledge making it possible for them, and only them, to arrive at sound political judgments about the arms race.”

They do not: these people are often too concerned with their own wonky limited worldviews to come to reasonable conclusions about something this important.

Dr. Scheber overplays the importance of “reliability” in his interview as do many many weaponeers — no surprise, that has been their job for decades and decades.

But reliability, and the alleged attendant testing, are not that important in matters of deterrence.

I made a stab at this a few years back and hope to write up a more detailed article sometime:

http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/reports/redefining-deterrence/redefining-deterrence-is-rrw-detrimental-to-us-security-ca

Thanks for the comment, and also thanks for posting the article. I ran across it (of course) multiple times since its publication, since I’ve been interested in the CTBT for a while.

Again, like I said in another comment here, there will end up being some kind of bargain, or the treaty just won’t fly with enough Senators to get 67 votes.

I’m enough of a pessimist to be amazed when anything passes the Senate, but that’s another story…

The current situation is that the US will not be testing, but there is no CTBT to provide an impediment, such as it is, to testing by potential proliferators.

That does not seem to be a very useful position for us to be in.

Whether or not the verification system is adequate to deter very low yield tests by the Russians or Chinese is not a question that matters very much – our deterrent will remain sufficient for a very long time. The verification system is very effective against possible proliferators, and that is what really counts.

If the CTBT would provide a disincentive for proliferation, and I think it would, then it would be our gain against very little loss.

I think Mr. Scheber’s response to the last question is his weakest. Surely he can do better than to trot out that faithful old dog, the car analogy – this isn’t the WSJ!

More fundamentally, it is my understanding that testing has *never* provided any statistical evidence that the weapons in the stockpile work – there hasn’t been nearly enough tests conducted to conclude that with a sufficiently high level of confidence. To continue that poor tortured analogy, what’s been done in the past is like starting one car in a whole suburb of similar cars, and trying to draw conclusions about the reliability of the remainder from that.

Testing as conducted by the United States prior to 1992 was not intended to statistically validate specific weapons designs, but to validate the design process. If the current generation of weaponeers have produced a hundred unique gadgets, pointed to each and said “this is a nuclear device that will produce a yield of X kilotons”, and are proven right every time, that produces on the order of 99% confidence that any future gadget called upon for a nuclear Kaboom will perform as advertised – even if it is a unique design that has never been tested before. The process for producing new but functional nuclear gadgets, is shown to work.

Of course, the actual track record is rather less than 100/0. And that was a previous generation of weaponeers, who were less than 100% effective in transferring their mojo to the new guys. And the tests were almost entirely of new-build gadgets that had not been exposed to realistic operational environments…

This was a fair test philosophy for the Cold War era, with ongoing testing and with multiple new warhead designs entering service every decade. For the new era, where the plan is to point to the last set of tests and say, “on the basis of those tests all may be confident that our warheads will work for the next hundred years”, you would want to do things differently – not that the test heritage we have is worthless, just suboptimal.

Mr. Scheber’s concern about the “definition” of a “nuclear explosion” is an exercise in hair-splitting: Yes, you can draw a finer and finer and finer line but it just doesn’t matter. So what if Russia toes the line of criticality? I’m not saying they do so, mind you — I don’t know, but I do know that nothing they might learn this way is of any military or security significance, and certainly not beyond what can be learned by tests we conduct on the safe side of the line and with the aid of our petaflop computers.

Scheber complains that Russia and China have not placed IMS sites as close to their historic test sites – by at worst a modest factor of four – as the US has. He comments, “Now, the seismologists have explained that there’s a rationale for that involving different kinds of soil, but it shows a lack of good faith at least by Russia and China.” On the contrary, it is perfectly reasonable given the geologic differences and making an issue out of it shows Mr. Scheber’s lack of good faith.

Finally, he plays this little word game: “Testing provides evidence that warheads either do work or do not, or work partially. And so stockpile stewardship can tell you that there’s no evidence that the warheads will not work.”

On the contrary, testing provides very weak evidence about the reliability of warheads, and stockpile stewardship entails the kinds of inspections, testing and analysis of components which we have always relied on to establish a basis for estimation of reliability. Stockpile stewardship provides positive evidence that the warheads will work, because it tells us their physical condition, and that is the only evidence upon which a belief in warhead reliability has ever been founded. It is far stronger evidence than would be provided by a renewed testing program, which would at best provide reassurance that the laws of physics have not changed in some way which only nuclear explosion tests would reveal.

If this is the best the opposition has to offer, the intellectual support for CTBT ratification is strong indeed.

Mr. Scheber inaccurately characterizes the consensus views of the Strategic Posture Review’s members. The reference to “apparent” Russian low-yield testing is contained in the section of the Review describing the views of opponents of CTBT ratification. It is not the consensus view of the Commission.

The agreed scope of the CTBT: that it bans all nuclear explosions of any yield, however small, is not a least common denominator among the negotiators in the CD. It is the demarcation between prohibited nuclear explosions, and “activities not prohibited,” which include hydrodynamic testing, inertial confinement fusion, fast critical reactors, and other experimental activities involving the release of nuclear energy that the U.S. successfully excluded from the scope of the Treaty. This required delegations that proposed their inclusion to agree to the demarcation. The text of the CTBT’s scope article was negotiated with the text of the LTBT as the basis, and extends the LTBT’s prohibitions on nuclear explosions to everywhere. Thus the agreed scope of the ban is in fact well defined.

The document from the President transmitting the CTBT to the Senate in September 1997 expands on the information here in its article-by-article analysis of the Treaty.

Regarding the Russian colleagues Mr. Scheber and others have discussed the scope of the Treaty with who “verify” a different understanding of scope, the responsible Russian official, Amb. Yuri Kapralov, in presenting the CTBT to the Duma in January 2000 for its approval, explicitly included so-called hydronuclear explosions as within the scope of the prohibition on all nuclear explosions: “Qualitative modernization of nuclear weapons is only possible through full-scale and hydronuclear tests with the emission of fissile energy, the carrying out of which directly contradicts the CTBT.”

The Russian chief negotiator, Amb. Yuri Berdennikov, states in his article on the negotiations (CTBTO Spectrum No.7, p.10) that “The difficult negotiations resulted in a compromise. On the one hand, the Treaty prohibits any nuclear explosions however low the yield, and on the other hand, it permits experiments with nuclear weapons, including those of the explosion nature, but under the condition that they are purely chemical (the so called ‘hydrodynamic experiments’).”

Thank you so much for your comment. This is exactly what I was hoping for: a discussion thread with solid references (I’m going to go look up CTBTO Spectrum No.7, p.10) as well as opinions. I’m honored and very pleased that you’ve taken the time to clarify some of the issues brought up in the interview. I’ll be writing a final piece, sort of a wrap-up/conclusion piece, in a week or so. If you’re interested in corresponding further, let me know.

Thanks again.

Grigory Berdennikov’s essay, “The history of CTBT negotiations – a Russian perspective,” is here:

http://www.ctbto.org/fileadmin/content/reference/outreach/spectrum_issues_singles/ctbto_spectrum_7/p10_11.pdf

One interesting bit concerns the proximity of monitoring stations to test sites. It reads,

“Certain differences emerged on the location of the International Monitoring System (IMS) stations. The Russian delegation insisted that the Treaty should provide for such locations of the IMS stations that would ensure equal transparency of the existing nuclear test sites. In the Cold War years, the Russian test site in Novaya Zemlya was tightly monitored by seismic stations in Scandinavia, while the United States test site in Nevada was practically monitored only from rather long distances and with a high detection threshold. At first, this proposal met strong objections, but in the end other delegations had to admit that the Russian claim was justified. The current Treaty envisages an IMS network that meets the principle of equal transparency of the test sites.”

It is true that the CTBT does not effectively prohibit Russia from conducting ultra-low-yield nuclear tests; even if everyone agrees that such things are prohibited, they can be concealed or camouflaged beyond the possibility of verifiable detection.

It is not clear why this would place the United States at any great disadvantage relative to Russia. Russia already knows how to build bombs that work, and there is no prospect of their learning to build bombs that work hugely better. The bombs they have and the bombs they can build will eventually degrade to uselessness, but ultra-low-yield testing will only somewhat delay that process and I expect the CTBT will pass into irrelevance one way or another long beforehand.

As an argument for not ratifying the CTBT here and now, this one is rather weak.

Each State Party undertakes not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion, and to prohibit and prevent any such nuclear explosion at any place under its jurisdiction or control.

What about NIF? Imploding fusion fuel in a hohlraum so it ignites and pretty much explodes is, if tiny, still kind of weapon-like. Which is what NIF was built for, after all.

It’s been a question of some dispute for a long time now. The official US position has of course been that NIF ignitions are neither nuclear weapons test explosions nor nuclear explosions in general. But it’s a whole other kettle of semantic fish to get into (what is a nuclear explosion?) — perhaps a topic for a future ACW post?

Scheber raises a red herring or two: the CTBT can always be exited — here is what Bill Clinton said:

http://www.acronym.org.uk/dd/dd18/18lett.htm

“The US regards continued high confidence in the safety and reliability of its nuclear weapons stockpile as a matter affecting the supreme interests of the country and will regard any events calling that confidence into question as ‘extraordinary events related to the subject matter of the treaty.’ It will exercise its rights under the ‘supreme national interests’ clause if it judges that the safety or reliability of its nuclear weapons stockpile cannot be assured with the necessary high degree of confidence without nuclear testing…..

If the President is advised, by the above procedure, that a high level of confidence in the safety or reliability of a nuclear weapon type critical to the Nation’s nuclear deterrent could no longer be certified without nuclear testing, or that nuclear testing is necessary to assure the adequacy of corrective measures, the President will be prepared to exercise our ‘supreme national interests’ rights under the Treaty, in order to conduct such testing.

The procedure for such annual certification by the Secretaries, and for advice to them by the NWC, US Strategic Command, and the DOE nuclear weapons laboratories will be embodied in domestic law.”

One thing the Nuclear Weapon states need to be careful about is being up front in any precise requirements that CTBT may have apply to non-Nuclear weapons states.

The NPT is currently suffering because the powers-that-be (US, UK and others it can influence on the UNSC) regularly over-reach in what they hope to have covered under existing IAEA safeguards. e.g. It would have been better if the Additional Protocol was thought of beforehand instead of trying to smuggle it into the NPT/IAEA later.

e.g. In Jeffrey post about compliance, we see the same old hackneyed IAEA phrase that Iran isn’t providing assurances that Iran’s nuclear program is exclusively peaceful.

Well guess what? Iran has no obligation to provide such assurances in the absence of ratifying the AP.

Because most of the requests to visit various Iranian sites that are stated by the IAEA in its reports are covered by the Additional Protocol, Iran has no legal obligations to grant them.

Iran has stated that, if its nuclear dossier is returned to the IAEA – its rightful place – it will begin implementing again the provisions of the Additional Protocol on volunteer basis until Iran’s parliament ratifies the Agreement.

At the same time, the Agency has carried out many unannounced visits to Iran’s nuclear sites. Such intrusive and unannounced visits are an important part of the Additional Protocol. Therefore, Iran is still selectively and voluntarily carrying out some provisions of the Additional Protocol. That is a positive aspect of Iran’s behavior which is overlooked.

In any case, there is nothing that authorizes the IAEA or Amano to investigate Iran’s missile program unless there is evidence of nuclear material involved — which the IAEA has said there isn’t.

The IAEA also stated that Iran did not allow it to visit and inspect Iran’s under-construction research reactor in Arak. But, such visits are covered by the modified text of the Subsidiary Arrangements General Part, Code 3.1, of the Safeguards Agreement.

Iran had agreed to the modified text, part of which states that Iran must allow inspection of the under-construction sites. However, because the EU3 reneged on its promises, Iran suspended the implementation of the modified text in February 2006, and went back to its original Safeguards Agreement, signed in 1974. The original Subsidiary Arrangements state that only 180 days prior to the introduction of any nuclear material into a nuclear facility does Iran have the obligation to allow visits to and inspection of the facility. Thus, once again, Iran has no legal obligations towards the Agency regarding the Arak reactor.

Thus, overall, despite the propaganda and bogus alarms the IAEA report actually indicates positive developments in the thorny issue of Iran’s nuclear program. Iran’s legally-speaking relative openness of its uranium enrichment program should be taken for what is intended for: declaring that Iran is willing to compromise.

Similarly, if there are things that the NWSs want the NNWSs to do re. the CTBT: speak now! Please don’t try to sneak in a CTBT AP after the fact and pretend that it applies retroactively to every NPT member.

This just looks bad and is in fact illegal.

The missing piece of this debate is that (a) testing is linked to warhead reliability, and (b) the required level of reliability depends on what you’re aiming at, and what probability of destruction of those targets you might require.

If our deterrent threat is to destroy enemy cities or industry — and our employment plan is to do that if deterrence fails — then hopefully deterrence will hold, and if it doesn’t…well…we don’t need such high levels of reliability or certainty about yield.

If our deterrent threat is ambiguous with regard to targets (as it currently is) — and our employment plans in some circumstances would be to focus on defending our allies or ourselves by rapidly destroying enemy NW — then hopefully deterrence will hold, but if it doesn’t we better have a good sense of the actual reliability (meaning p(detonate) and yield variance) of our weapons.

So does testing matter, and how much reliability is enough? It depends on (a) the nature of our deterrence threat, and (b) how we would want to employ them if adversary actions force us to.

Those who say “reliability doesn’t matter” can offer a (debatable) argument about what deters, but I don’t see they have any argument at all about what capabilities we might want if deterrence fails.

Actually, there are no missing pieces to the debate since we have been through this before: If you are really concerned with weapons’ systems reliability for warfighting then I suggest concentrating on improving the reliability of the delivery system — as I clearly mention in my Bulletin article:

“the overall reliability of the weapon system is dominated by the intercontinental ballistic missile delivery system–of 2,160 test launches, approximately 15 percent resulted in some type of delivery system failure that would have prevented the warhead from reaching its target.″

By comparison, the warheads’ reliabilities are in the upper 90s% ranges, with high confidence levels.

So this is a repetition of a previously disposed of red herring.

If in 70-100 years the reliability of the warheads starts approaching that of the delivery system, then — as FSB points out above — there is a “supreme national interests” exit clause for possibly testing.

From 1958 to 1996, the Stockpile Evaluation Program sampled nearly 14,000 weapons; of these, only about 1.3 percent were found to have failures that would have prevented them from operating as intended.” ref: General Accounting Office, “Nuclear Weapons: Improvements Needed to the DOE’s Stockpile Surveillance Program,” PDF GAO/RCED-96-216, 1996.

A good unclassified summary is:

http://www.ucsusa.org/assets/documents/nwgs/rrw-workshop-summary-fnl-122006.pdf

The footnotes are especially interesting. e.g. a warhead that explodes with a yield 10% different from its design yield may be considered “unreliable” in internal USG doc’s: even though it may properly annihilate a city.

Note that in the new N.P.R. our leaders have spelled out what the fundamental role of nuclear weapons is — and it is not military warfighting:

“The fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons, which will continue as long as nuclear weapons exist, is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners.”

i.e. deterrence is the fundamental mission, not warfighting.

Even if it were warfighting you need to worry about the delivery systems about a century before you need to start worrying about the warheads. And if there is any problem discovered in 2096 with the warheads, the supreme national interest exit clause exists in the CTBT.

Almost all arguments in favor of increased reliability of nuclear warheads are fatuous, misleading and/or irrelevant — both to deterrence and warfighting.

Yousof,

This is a thread about the wisdom of ratifying CTBT. Others who have contributed to this thread (e.g., Schilling, Gubrud) have been going back and forth about the relationship between time and reliability in the absence of tests, i.e., will time erode warhead reliability in a manner that will be difficult to detect without tests?

My post is on the opposite side of the equation: how much reliability is enough? A few people have posted (above, in this thread) things that suggest that even low levels of (or uncertain) reliability will deter. Perhaps they’re right. My post is pointing out that the actual employment of weapons — if deterrence fails — might require high levels of reliability if our targets are not cities.

Your response is that *currently* warhead reliability is substantially higher than delivery system reliability. Perhaps. But the question is whether we can be confident of those high warhead reliability numbers in 2 decades, or 4 decades, etc., without testing. Perhaps those percentages would drop precipitously? (that’s the Schilling / Gubrud discussion).

But we need to be clear, and we need to be explicit: as we contemplate the relationship between time vs. reliability (as it affects our decisions to ratify CTBT), we need to be explicit about what our retaliatory missions are, and what those missions require with respect to *system reliability* (warhead reliability * delivery system reliability). Saying we could still “annihilate a city” — as you just wrote — even if some combination of warhead or delivery system reliability drop may simply be irrelevant if our retaliatory doctrine or employment plans aim these weapons against things much harder to destroy.

Daryl

Daryl,

Yousaf is quite correct: I am not sure of your background but anyone with an engineering/physics background will tell you that what controls the “reliability” of a system is the lowest reliability component.

So instead of making a fuss about warheads your concerns would be more believable if you launched a crusade to improve the reliability of the ICBMs and submarines, and bombers which suck in comparison to the warheads.

Further, as pointed out above the deterrence mission is the important one according to the NPR, despite what you may think. Sure, warfighting should not be dismissed but if you are serious about warfighting start making better ICBMs, subs and bombers. Forget about the warheads — they are fine. The JASON group has said they will be OK for the next century.

Lastly, your whole point is not terribly relevant since the need to possibly test in the distant future is not a reason to not ratify the CTBT: see my link above.

There is a supreme national interest clause that IF we need to test, we may exit the treaty.

So your interjection into this discussion is interesting but not relevant and generally misleading.

I hope you will rest easier and relax your preoccupation with the non-issue of warhead reliability.

The warheads’ pits will be OK for the next century or so — yes the LEP and SSP should go ahead and if something fishy is found it will be addressed, CTBT or not.

“what controls the “reliability” of a system is the lowest reliability component.”

From the standpoint of probability theory, if a system relies on several sub-systems all working, and if the (e.g.) boosters, and guidance system, and warheads either work on not on a fairly “independent” basis, then the odds of the total system working is a *product* (i.e., multiplication) of the probability of the sub-systems. Significant reductions of the most reliable components’ reliability would have the same scale of effect on the aggregate reliability as reductions of the probability of the least reliable components working. I can see why engineers would spend scarce time improving the least reliable parts of complex systems, but that’s a different matter. The point is *if* time with out testing reduces warhead reliability, that affects net probability of the system functioning independent of whether the delivery systems are reliable or not.

“the deterrence mission is the important one according to the NPR”

Wasn’t it the very first observation of game theory last century that decisions at one decision point are (or should be, if one is rational) affected by expectations of what will happen at the decision points lower on the tree (i.e., later)? From the early days of game theory and deterrence theory people have recognized that one’s ability to carry out retaliatory missions (which could mean more than annihilating cities) affects not only what would happen if deterrence fails, but affects deterrence itself.

“testing has *never* provided any statistical evidence that the weapons in the stockpile work – there hasn’t been nearly enough tests conducted to conclude that with a sufficiently high level of confidence. ”

This is an interesting argument by KME, and I’d like to see it fleshed out. Jeff Forden wrote an interesting article about 8 years ago on what one could estimate about W76 reliability based on a small number of tests; it demonstrates how one can put a lower bound on reliability in a statistical sense with a very small number of tests. There were some small problems with Jeff’s original argument (that he discovered and pointed out to me later — a sign of a good scholar), but the overall method is good.

Overall, I feel we’re talking past each other a bit. There was a debate – which I didn’t join — about whether we can be confident about warhead reliability as decades pass without testing, and whether the non-testing means of inspection would reliably detect flaws. I’m not putting my toe in the water on that debate. I’m saying: the view that even substantially reduced reliability is acceptable because even unreliable weapons should deter b/c it’s easy to destroy cities needs to be thought through more carefully, because US deterrent threats do not all hinge on us retaliating against cities and industry — but against much harder targets.

But…I think we’re talking past each other.

Indeed we are talking past each other a bit since you don’t address or acknowledge my meta-level point: the CTBT can always be exited if there is a supreme need — here is what Bill Clinton said:

http://www.acronym.org.uk/dd/dd18/18lett.htm

That said, the JASON group has concluded that nuclear weapons’ pits will be OK for the next century or so and that testing is not needed.

Since the SSP and LEP are in place, there exist mechanisms to ferret out any future problems — without tests.

If experts feel — and politicians allow — then tests could be done, even if we had signed the CTBT — if such tests could reveal any further important data. Such tests would not attest to the reliability of the actual fleet of warheads, as kme correctly points out.

Your preoccupation with reliability would be better directed at making more reliable ICBMs, subs and bombers.

The reason engineers looks at the least reliable components to improve is that the fractional change in going from, say, a 30% to 60% reliable component is bigger than in going from 98.4% to 98.7%.

However, I suggest you contact e.g. someone in the engineering dept to better explain this business to you: it is all fairly elementary but not a particularly good use of my time, or of any deep interest to the other technically-informed people on the blog.

Thank you for the discussion.

D. Press: “US deterrent threats do not all hinge on us retaliating against cities and industry — but against much harder targets.”

In fact, you are wrong here if you are actually talking about deterrence.

The deterrence threat of a 98% or 90% or 70% reliable weapon (in case this reliability is somehow known to one’s adversary) is the same.

The Russians or Chinese (the only ones with sufficiently hard targets for the argument) will not second guess and pooh-pooh the reliability of our 300-400kT nuclear weapons. deterrence

Warfighting is another matter: but note, as Yousaf points out in the link to the RRW workshop, a warhead may be tagged as unreliable if it falls short by 10% in its estimated yield. This 10% margin is due to how well we can measure the yield — not to do with actual military requirements.

Further, any target of significance has several nukes targeted on it such that p(destruction)~1.

And, testing does not tell you about whether the yield of the next bomb of the same flavor will be within 10% of its design yield. (kme’s argument)

Lastly, if anything terribly wrong was discovered — and even if we had signed the CTBT — we could use the “supreme national interest” escape clause to test.

No problem at all with signing on to the CTBT as regards warhead reliability.

And warhead reliability, generally, is a tempest in a teapot.

Don’t worry. Be Happy.

If we assume, somewhat simplistically, that the success of a weapon is a binary value, i.e. either it kills the target or not, and then that the probability density of this value is close to unity and is the product of two factors both close to unity, then we can write

(1-a)(1-b)=(1-c),

where (1-a) and (1-b) are the two factors (say, warhead reliability and delivery system reliability) and (1-c) is the resulting system reliability. Expanding, we get

1-a-b+ab = 1-c.

If a and b are both small, e.g. 10%-15%, then ab will be very small, e.g. 1%, and can be neglected. In that case, we have

c = a+b,

i.e. the “unreliability” of the system is the sum of the “unreliabilities” (failure probabilities) of the two parts. Not the product.

Now, reducing a and reducing b in order to reduce c will both have costs, and for a fixed budget, if a’ is the reduction of a obtainable by spending another dollar on reducing a, and likewise b’, and if a’ and b’ are both decreasing functions of a and b, the optimum budgeting will occur when a’=b’, and if the operations managers (like Mr. Scheber) have done their jobs, that’s already where we’ll be.

Thus the argument that it would be better to spend more money on reducing the higher failure rate of delivery systems is not necessarily correct since the cost of doing so might be greater. (One can easily construct this argument in a more sophisticated form in terms of the relative costs of the two components and the relative costs of reducing the failure rate of each component by some incremental fraction.)

As for establishing the reliability of warheads through testing, if the failure rate is small (again, less than 10%) it would take a very large number of tests to distinguish with any accuracy between the cases of say 5% and 10% failure. Roughly speaking, the fractional accuracy of the success rate measured will be the inverse of the square root of the number of tests. Thus, to measure with 5% accuracy one needs 20^2=400 tests. To see this argument fleshed out, consult any elementary textbook on statistics.

Mark,

You are clearly a smart guy. What I find surprising is not that all people — both smart and dumb — make mistakes; we all do that. But what’s with the pretty shocking attitude (suggesting that I “consult any elementary statistics textbook)”?!? Especially b/c I’m pretty sure that **you’re the one making the stats error here.**

You write:

“If we assume, somewhat simplistically, that the success of a weapon is a binary value, i.e. either it kills the target or not, and then that the probability density of this value is close to unity and is the product of two factors both close to unity, then we can write

(1-a)(1-b)=(1-c),

where (1-a) and (1-b) are the two factors (say, warhead reliability and delivery system reliability) and (1-c) is the resulting system reliability. Expanding, we get

1-a-b+ab = 1-c.

If a and b are both small, e.g. 10%-15%, then ab will be very small, e.g. 1%, and can be neglected. In that case, we have

c = a+b,

i.e. the “unreliability” of the system is the sum of the “unreliabilities” (failure probabilities) of the two parts. Not the product.”

Actually, it’s the product.

Imagine in your example that the first “factor” in the system’s reliability has a reliability of 0.4, so then a=0.6. The second factor has a reliability of 0.3, so b = 0.7. In that case, solving your equations shows that reliability = 1-0.7-0.6+0.42. The total, of course is 0.12, or 12%.

But that shouldn’t be surprising because one could have simply reached that answer by **MULTIPLYING**, exactly as I argued: 0.4 * 0.3 = 0.12. This is straightforward and shouldn’t surprise because we all know that the joint probability of two independent events is calculated by multiplying the two probabilities together.

The reason your calculation led you to think it was additive rather than multiplicative is that you picked the special case in which reliability of both systems is very high — in which multiplication still produces the right answer, but adding as you did (and discarding ab) gets you close. Even then, the actual system reliability is properly estimated by multiplying but your method (casting out the ab term and simply adding) produced a number that was close to correct.

OK — maybe there’s some obscure reason that I’m wrong, and if so I trust you’ll point that out to me and the group. (Though I’d bet my expensive mountain bike that I’m right, and that one calculates joint probabilities of roughly independent events the way I described above). But even if that happens, let’s agree that, in the future, we’ll disagree professionally, i.e., without telling people to go consult elementary textbooks. (And frankly you were no worse in this matter than FSB and Yousaf.)

I’m sure I’ve been condescending before too. This board has smart folks on it and we can all learn from each other if we try.

(I’m not dodging the other points in your post — but I think the list has exhausted its interest in this thread. If anyone is actually interested in my response to your other points — including you — I’d be happy to either post it or email it privately.)

Best,

Daryl

Why not just send Mark an email to discuss this?

Frankly, I did not check Mark’s or your math because it is rather simple, as I explained before:

“The reason engineers looks at the least reliable components to improve is that the fractional change in going from, say, a 30% to 60% reliable component is bigger than in going from 98.4% to 98.7%. ”

And as I said before, the warheads’ pits will be OK for the next century or so, according to the JASON group. And if SSP finds anything worth testing — even if the CTBT is ratified — we can use the escape clause of supreme national interest and test away.

And btw, testing tells you very little about the reliability of the next bomb of the same flavor — so it is not relevant for the purpose you advocate.

There is no issue — the warheads are fine and will be for decades if not a century and are being monitored. The delivery systems are in worse shape.

These facts will allow you to make a judgement about what components of the weapon system ought to be addressed and what components we need not worry about for decades.

In any case, the discussion is altogether irrelevant for whether or not we should ratify the CTBT.

Apologies if this seems condescending — it is probably just an artifact of frustration at the fact that you repeatedly appear not to offer any credible defense of any relevant argument.

You seem to be saying “I wanna have the option of testing cause it makes me feel good” when the CTBT indeed does offer the option of testing for “supreme national interests”.

I am not sure what point you are repeatedly trying to make. Thus my frustration and apparent condescension.

Daryl,

My math isn’t wrong, you just didn’t understand it.

Yes, if an outcome depends on two independent events both occurring, the probability of that outcome is the product of the probabilities of the two independent events.

Thus the probability of a successful mission for a nuclear weapon can be factored as the product of the probability that the delivery system works and the probability that the warhead works.

The probability of a failure is a bit more complicated because either of two events (failure of the warhead or of the delivery system) can cause failure. If both are rare events, the probability of system failure is approximately the sum of the two independent probabilities of component failure, as I explained.

If a is the probability of warhead failure, then 1-a is the reliability of the warhead. Similarly, if b is the probability of delivery system failure, 1-b is the delivery system reliability. Then c is the probability of joint system failure, and 1-c is the joint system reliability. The equation I wrote

1-c = (1-a)(1-b)

correct, and the rest is algebra.

Note that the overall probability of system failure is not exactly the sum of the two component failure probabilities, but if those are small (which they are) then the product term is very small and is also opposite in sign, i.e. the product term actually increases the reliability.

Mark, what you’re missing is that you can’t compare an increase in reliability from 85% to 86% with one from 97% to 98% – although these both give a similar increase in overall system reliability (the 85% to 86% increase actually gives more bang for the buck), going from 85% to 86% is much, much easier (cheaper).

Improving a component’s reliability from 85% to 86% translates to a 7% reduction in the probability of failure; improving a component’s reliability from 97% to 98% translates to a 33% reduction in the probability of failure. Improving the reliability of the 85%-reliable component is the low-hanging fruit.

kme-

I don’t know why you think I am missing your point. What in what I wrote was inconsistent with what you are saying? The point you are missing is that it might actually be more expensive to improve delivery system reliability – your argument is valid for a given type of system but does not take into account the differences between warheads and delivery systems. The latter are far more complex systems. This is very probably the reason that they are less reliable.

Also, kme’s comment is very important but lost in the noise: “…testing has *never* provided any statistical evidence that the weapons in the stockpile work – there hasn’t been nearly enough tests conducted to conclude that with a sufficiently high level of confidence. To continue that poor tortured analogy, what’s been done in the past is like starting one car in a whole suburb of similar cars, and trying to draw conclusions about the reliability of the remainder from that.”

A non-issue, esp. in light of the “supreme national interest” exit clause.

Hi Page –

Don’t know if you’ve done so yet, but you should chat with Greg Van Der Vink. We worked with him on techie aspects of CTBT ratification recently.

Jodi

Thanks for the suggestion. I’m trying to reach a few people; I’ll add him to the list.

Is the U.S. prepared to make do without nuclear weapons? Cause that’s what it will boil down to. The nuclear complex is a living monster. It will die when not fed. That goes all the way from mining to a full test of the weapon system from C2 >>> booom (like Frigate Bird). Just because death might only occure in, say, 30 years it is still death. And since I don’t think the U.S. is willing to become de-nuclearized let’s be honest and consequential and continue to fed the monster the small bites it needs, instead of discovering in 25 years that the monster needs a life support machine and a lot of money to restart. Also don’t forget: Testing is not only done for oneself, but also for the “other side”. Part of the pissing contest aka nuclear deterrence. (Forget about math and numbers – it’s about BELIEF). Show the other guy without the shadow of a doubt that you can blow up everything and its mother. In short: Regular testing of the whole complex is mandatory.

That regular testing is not mandatory is shown by the fact that nothing untoward has happened since 1992.

As argued above the “must test regularly” crowd would be more believable were they to advocate for improving the delivery systems.

The JASON have said the existing pits will be OK for a century.

The CTBT allows testing for supreme national interests, in any case.

Want more reliable warheads than the 99% reliable ones we have? Try U gun-type weapons.