By now, New START aficionados (if that’s the right word) will know all the talking points about missile defenses. Treaty critics in search of unacceptable restrictions on interceptors have homed in on Art. V, Paragraph 3, which prohibits either the conversion of ICBM silos or submarine missile tubes into interceptor launchers, or conversion the other way around. Administration officials and military leaders have responded that there were never plans to conduct such conversions, and it’s more cost-effective and technically feasible just to dig new interceptor silos if necessary. Fair enough. But why is the conversion ban in the Treaty text? What’s the point of having it there?

Back in April, Jeffrey pointed out one good reason: putting new interceptors into dual-purpose silos probably would have brought the interceptors into the scope of the New START inspection regime. And earlier this week, Ivan Oelrich similarly observed that, absent the two-way conversion ban, enforcing the Treaty’s limits on ICBM or SLBM launchers (i.e., silos or tubes) would have become more complicated. It probably would require more inspections to verify that interceptor silos were not, in fact, treaty-limited ICBM silos.

The apparent point, then, is to keep interceptors out of the Treaty’s numerical limits and inspections regime. That seems like a straightforward and perfectly adequate explanation for the conversion ban. So the additional explanation from STRATCOM commander Gen. Kevin Chilton, given at the June 16 SFRC hearing, is that much more interesting.

The World’s Biggest Game of Russian Roulette

First off, Chilton endorsed the view — voiced by Sen. Dick Lugar — that dual-purpose silos would have to count against the ICBM or SLBM launcher limit. He considered this disadvantageous; why trade SLBMs for interceptors if you can have both instead? He also made the familiar point about cost and technical disincentives for conversion. But then the STRATCOM commander offered an altogether different explanation about why the two-way conversion ban is an all-around good idea:

From an ICBM field perspective… there would be some issues that would be raised if you were to launch a missile defense asset from an ICBM field, with regard to the opposite side seeing a missile come off and wondering, well, was that a missile defense — a defensive missile — or is that an offensive missile?

In another context, this issue has been called “the ambiguity problem.” If the Russians don’t know whether the missiles flying at them are defensive interceptors or nuclear-tipped, they might respond with a nuclear attack. As discussed in this space last year, GMD interceptor missiles launched from North America against inbound North Korean ICBMs would fly out in the direction of Russia. In some scenarios, the intercept attempts would actually occur over Russian skies.

A Picture is Worth 1,000 Missiles

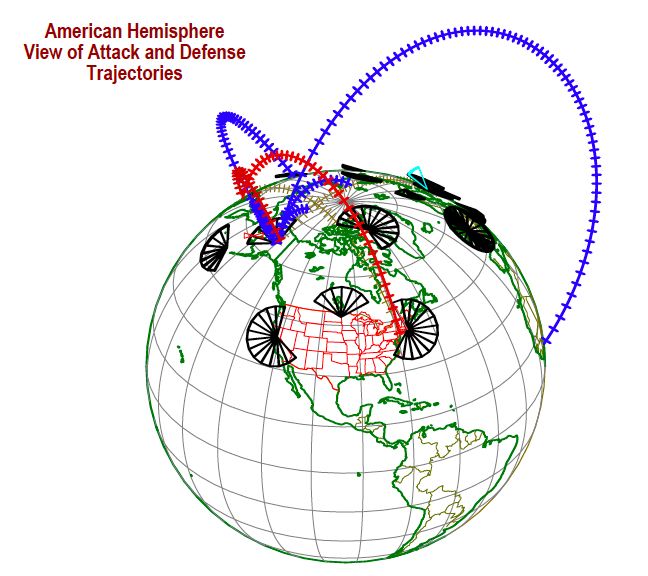

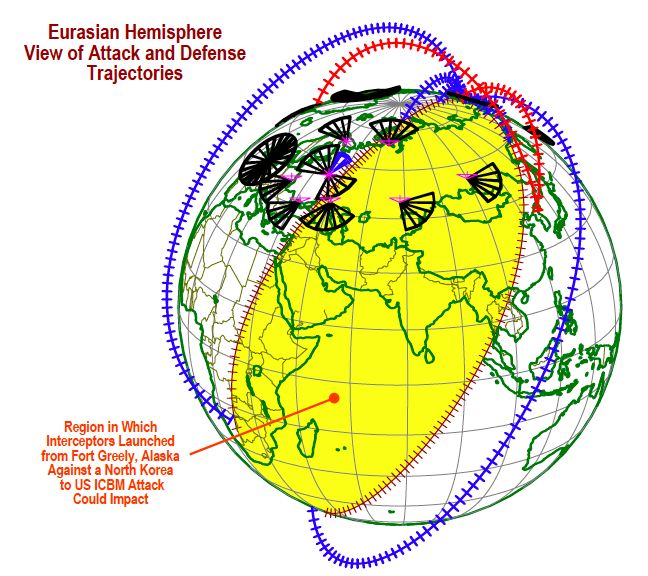

In case you missed the earlier discussion, here are the illustrations again. Observe carefully. The two red tracks are North Korean ICBMs shown bracketing potential North American targets. (Hawaii is a fundamentally different scenario.) The blue tracks are GMD interceptors flying out from Ft. Greely, Alaska against the attacking missiles. The black fans are early warning radars, both America’s and Russia’s.

Now let’s consider the Russian view of this scenario. Note the yellow zone, which shows where the interceptors may overfly and re-enter the atmosphere, and where it overlaps with Russian territory. With two interceptors flying out against each attacking missile, absent one or more major technical failures, one to two interceptors per missile would fall to Earth inside this area.

Even in the best case, the opportunity for an unfortunate misunderstanding gives one pause. Don’t try this at home.

Now just imagine that the interceptors are flying out of the ICBM field at Minot AFB instead of Ft. Greely. Add to that the possibility that Russia’s early-warning network may not detect the North Korean launch in the first place, and this scenario could spoil your entire day.

Perhaps the concern is merely hypothetical, since we’re not going to use GMD, barring some horrible miscalculation. As Kim Jong Il once remarked, “It is ridiculous to claim that North Korea will be able to beat the U.S. by developing intercontinental ballistic missiles and blasting them off to the U.S.” Nevertheless, in the run-up to both North Korean ICBM tests, back in 2006 and 2009, there was a clamor to shoot that missile down! There will probably be additional ICBM tests and further calls for interception. Some future President might yield to that sentiment. If so, I sure hope that she remembers to tell the Russians in advance.

In short, the two-way conversion ban is there for good reasons. Missile-defense advocates, certainly, should be only too glad to embrace a provision that keeps defenses out of the Treaty limits, keeps inspectors away from interceptors, and reduces the chance that an intercept scenario will escalate into WWIII — a margin of safety that might make a future leader more willing to use GMD, in theory. The Russians may have raised the idea, as they’ve apparently expressed concerns about silo conversion potential before. Or the Americans may have raised it, for all of the reasons given above. Either way, both sides have sound reasons to want this provision in the Treaty.

You’ve answered a really interesting question — “Why would the United States NOT want to put missile defense interceptors in ICBM silos?” And the answer is because launching them could inadvertantly lead to World War III.

But that doesn’t answer the question that Senator McCain, and others have asked. Even if its true that we’d never want to do this, WHY is the limit in the treaty? Why did we include a ban that it is meaningless, as far as affecting our plans or operations?

The ban does make it possible to deny Russia access to interceptor silos in the monitoring and verification regime. And that includes the silos at Ft. Greeley (because it is a two-way ban, and, absent the ban, they’d presumably want to check out the interceptor silos to make sure they don’t hold ICBMs). But there’s a far more simple explanation for why we agreed to ban something we never wanted to do. Russia doesn’t like the fact that we converted 5 silos at Vandenberg. They either wanted those to count under New START (a bad precedent that could spread to Ft. Greeley silos), or they wanted us to convert them back. They harped on this a lot in the negotiations. So, we made a trade. They agreed to leave those five silos alone if we agreed we’d never convert anymore of them. We gave up something we didn’t want to do in the first place to shut them up about something we didn’t want to undo. We won on both counts. The benefits to us were very high (keeping the 5) and the costs were very low. For the Russians, the costs were high (they didn’t get access to any interceptor silos) and the benefits were very low.

So, bottom line, the critics argue that this is a concession to the Russians and proved that we were poor negotiators. In reality, we refused to concede what they really wanted, and gave them something they didn’t ask for and we didn’t mind giving up. Sounds like the Russians proved to be pretty poor negotiators.

Thanks for sharing this fascinating account. On this basis, we might conclude that Jeff and Ivan were looking in the right direction, but had no way of guessing how events unfolded across the table.

Still left unexplained is the exact nature of the Russian objection to the Vandenberg silo conversions.

Advocates of dual use conversion will likely focus on the conversion of SLBM tubes vice land-based, as was the case in discussions for deploying KEI in converted Ohio-class SSBNs. While technically feasible (setting aside for the moment the issue of missiles primarily fueled with hypergolics and their deployment in subs), the challenges of the CONOPS associated with this form of interceptor employment (stationing, communications, target updates to interceptor, etc.)are typically overlooked by said advocates…

w/r, SJS

Remind me why we (the US) should object to some reasonable provision for letting the Russians inspect interceptors now and then.

It’s certainly the case that GBI silos could hold a smallish ICBM, and maybe that a GBI modification, swapping burn-out velocity for payload, could be that smallish ICBM. What’s to be lost by letting Russian inspectors have access to a randomly picked interceptor in its silo a few times a year?

And, BTW, DARPA is looking at a hypersonic payload that would be boosted by an SM-3 Block II of the sort the US contemplates having in Poland and Romania at the end of the decade. (http://tinyurl.com/22owuzu) Questionable that it will ever become real, but overall it doesn’t seem unreasonable to accommodate concerns about such matters by agreeing to inspection.

An entirely fair question, Allen, and if you want to be very precise about it, the Treaty actually provides for two exhibitions of the five converted silos at Vandenberg AFB, so the Americans can show the Russians the features that distinguish converted silos from ICBM silos, and then give them a chance later on to ascertain (among other things) that the silos haven’t been changed back. (See the Seventh Agreed Statement in the Protocol.)

If we can accept Anon’s explanation above, it would seem that the Russians find silos that change back and forth to be very bothersome. So what’s gained most of all from the conversion ban is a clean demarcation of the two launcher types — ICBM launchers controlled by the Treaty, GBI launchers not controlled by it. That ought to make both sides happy.

For everyone’s reference, I will post Art. V Para. 3, the Seventh Agreed Statement, and the relevant excerpt of the June 16 SFRC hearings lower down in the comments.

If you want to see why letting the Russians take a look at a GBI every year in a converted silo, just check out slide 6 in this Power Point on the official Russian MOD website:

http://www.mil.ru/files/AMD5.ppt

The title of the slide is: The GBI ABM practically does not differ in size and shape from an ICBM.

If you thought getting the Russians to agree to a lot of things at JCIC was tough, wait for the first time they saw a GBI in the hole.

Former inspector,

Thanks for pointing out that Power Point presentation. I notice that a couple of slides later it details the proposals that the Russians say Gates and Rice offered orally in October 2007 and then left out of the formal document presented in November. The Power Point presentation is attributed to Baluevskii as chief of the General Staff, so it must date from some time between November 2007 and June 2008, when he stepped down.

None of the likely threats a BMD would be defending CONUS against would benefit much from at-sea basing. The angles just aren’t there.

Protecting Japan, Europe, or Hawaii are different stories, to some extent, but not what this system is designed to do.

Here are the source materials for this post and the discussion in the comments so far.

Art. V Para. 3 of the New START Treaty:

The Seventh Agreed Statement of the Protocol:

From the Q&A of the June 16, 2010 SFRC hearings: