As this penultimate year of the decade draws to a close, our thoughts naturally turn to all the changes we have seen. (Don’t ask me why this year and not next, there is just something special I suppose about seeing that tens digit change.) One thing that strikes me is all the convincing proof we had this year about the spread of sensors around the world. Sensors are becoming ubiquitous!

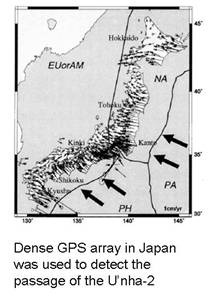

Nothing makes this clearer than the launch of the U’nha-2, North Korea’s third attempt to put a satellite into orbit. Not only did a high resolution photo-imaging satellite catch the actual launch, but it turns out that a vast array of GPS sensors spread over Japan sensed its passage through the upper atmosphere. I’m sure Wonk-readers can think of other examples that illustrate the spread of sensors around the world. (My favorite example involves Iraq, but I can’t really talk about that.)

But if the world has access to more and more sensors, it’s not clear we have the capability of analyzing all of the data. (I don’t mean the sort of brilliance Kosuke Heki, a geodesy specialist at Hokkaido University, displayed in analyzing the change in GPS signals the U’nha-2’s passage caused. That sort of creativity cannot be counted on as standard operating procedure.) It’s a lot like sitting down in front of Google Earth and simply scanning the Earth’s surface, looking for something interesting. You quickly find out you need to be clued into where to look. Dealing with this data overload will be the challenge for the next decade; when it starts in 2011.

Note: The figure above shows the dense GPS array with annual crustal strains.

“Don’t ask me why this year and not next, there is just something special I suppose about seeing that tens digit change”

It’s because there’s no “Year 0”. Thus we start with 1.. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, 10. The “10” year is the last year of the decade.

Yeah, I know, I have too much time on my hands… I know.

Fred, Fred, Fred,…

That is exactly what I’m saying.

There’s even more sensors than you think out there:

http://tech.yahoo.com/blogs/patterson/29720

Come to think of it . . .

Why don’t the laptop accelerometers linked to above support the CTBT in nuclear test sensing? That seems like it would be a very difficult signal to mask out given the large number of computers always on and listening. Perhaps the communications protocols would need to be designed so as to make the system impossible to spoof. I think it can be done.

Dude, we have a sensor network that can detect a supernova anywhere in our galaxy, fercryingoutloud.

That’s not Star Trek tech, it’s over a decade old.

Don’t expect the trend (more sensors, more monitoring) to reverse, it won’t. But it is true that using sensor net A to do unexpected job B will require some expert data handling that is likely to be a one-shot deal.

Dude,

Sensors that detect a supernova anywhere in our galaxy? That’s not decades old, thats thousands and thousands of years old!

John,

That’s a great idea! what do you think we would have to do to set up such a network of PC accelerator? Obviously write a program, but for this we also need to set up a social program to get people to volunteer to do it. Lets talk, perhaps we could actually get something like that funded.

Geoff,

Just as an aside, I’m pretty sure that the North Koreans (nor anyone else, for that matter) have not characterized the July 2006 long-range missile launch as an attempted satellite launch. I’m not sure why we should infer that it was, absent some additional evidence. So that makes this year’s event the second failed satellite launch, not the third.

Here is the statement of the North Korean Foreign Ministry about the multiple missile launches of July 5, 2006. (For a list of the missiles, see here and scroll down to the second half of the post.)

Note the differences between the 2006 event and the alleged satellite launches of 1998 and 2009: part of a barrage of missile tests, no claim of a satellite launch, no notification of danger zones. (There was a notification before the April 2009 launch, as part of an attempt to establish the international legitimacy of the test. The Foreign Ministry statement of July 2006 states why they chose not to provide notification of danger zones on that occasion.)

Josh,

I’m sure your memory of these launches is better than mine. On the other hand, it seems strange to me that they would test long range missiles as satellite launchers (which is what I believe they were doing) both before and after the spectacular 2006 failure but were officially testing a long range missile during that test. I hope we can find some “before the event” announcement to show it was a missile test and not a satellite launch attempt, which would settle the issue. But failing that, I will continue to think of it as a satellite launch that not coincidentally tested a long range missile. As to why they called it a successful missile test after the failure, I think that they did that to explain the lack of an orbiting satellite. Of course, that begs the question of why they said the 2009 test was a success. I have suggested my reasons for that but many people disagree with me.

I hate to drag us off-topic here, as the main subject of the post is clearly the thing, and very interesting, too.

Anyhow. There doesn’t appear to have been any advance notice of the 1998 or 2006 launches, so I’m afraid I can’t satisfy you on that point. Then again, it’s not clear why you couldn’t argue the exact opposite on the same basis. Silence can be tricky that way, and I wouldn’t stake anything on it either way, at least in this case.

The bottom line is, we see three failed launches of big rockets. In the first and third cases, the North Koreans claimed to have orbited a satellite, and eventually showed pictures of satellites. (It seems that the U.S. also detected an unexpected third stage in 1998, which suggests there was a bird.) In the second case, they didn’t so much as hint at a satellite, describing the launch bluntly as part of “missile launch exercises.” We may never know for sure, but I see no strong reason to reject that claim.

You ask a really good question about why the North Koreans would say one thing in 2006 and another in 1998 and 2009. Something to consider is the differing political contexts and justifications—when the North Koreans wanted to portray their missile development as peaceful and inoffensive, and when they wanted to portray it as an effective military deterrent. I may have to circle back to this topic later!

Josh,

Your logic is impeccable. So from now on, I suppose I should say “two or three satellite attempts, depending…” I look forward to reading what your write on the issue of declarations.

Geoff: The most effective way to start using the laptop accelerometers to look for nuclear tests would be to partner with the QCN guys at Stanford (who are looking for earthquakes), rather than duplicate their effort from scratch.