We usually think of the enrichment power of a centrifuge as fixed by its physical parameters. For a given gas, that of course is true. For enriching uranium hexafluoride, centrifuges with larger rotational speeds (the enrichment power of a centrifuge actually goes as the square of the peripheral speed) and longer rotor lengths have a greater separative work capacity. Thus, a P-1 has about 2.5 SWU capacity for enriching UF6 while a URENCO TC-12 reportedly has about 45 SWU.

What is often overlooked, however, is the effect of the gas on the enrichment capacity of a centrifuge design. (See equation 3 of Stanley Whitley’s “Review of the gas centrifuge until 1962. Part 1: Principles of separation physics.”) The gas properties enter into the equation in a variety of ways. First, the denser the gas, the better. Second, the more the species you are trying to enrich diffuses through the “carrier gas”—in this case He-3 diffusing through helium—the better. Finally, a centrifuge enriches a species faster if the mass difference between the two components of the gas is larger; in fact, it goes as the square of the mass difference.

The first and the third factors, density and the mass difference, favor the relative power of enriching uranium. (Here I have assumed that the number densities of helium and UF6 in the centrifuge are the same, which, of course, makes the density of UF6 about ninety times more dense than helium.) Helium is wonderful at diffusing through things, which is why most party balloons go flat and fall to the ground so fast. And He-3 through helium is no exception. It turns out that He-3 is about 13,000 times faster at diffusing through helium than a UF6 with U235 is at diffusing through U238 uranium hexafluoride. This is more than enough to compensate for both the mass difference and the low atomic mass of helium. Any given centrifuge should be (barring unforeseen practicalities) about 10 times better at enriching helium-three than it is at enriching U235. Thus, a single TC-12 centrifuge should have an enrichment capacity of 450 SWU-kg/year. That might be so large that it’s hard to balance the stages inside a URENCO cascade since URENCO apparently have fixed piping.

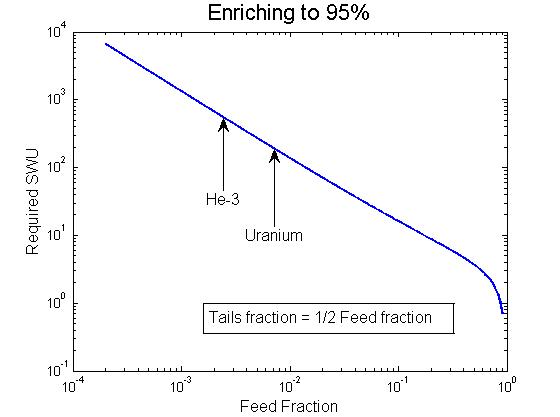

Total required enrichment capacity for a 95% product as a function of feed fraction assuming the tails are depleted to half the feed fraction.

However, it at least naively seems very good because the starting fraction of He-3 (at ~250 ppm) is considerably worse than the starting fraction of even natural uranium, or 0.711% of U235. If you want to enrich one kilogram of He-3 from its natural fraction to 95%, it takes 523 SWU as opposed to 189 SWU for uranium. This factor of more than two is, of course, more than compensated for by the improved enrichment capacity of each centrifuge. So the total amount of enrichment capacity needed is 63,000 SWU-kg/yr. It would take 140 TC-12s operating continuously for a year to enrich the required helium. (I haven’t bothered to find the optimal cascade size so this is a very crude estimate.) If, for some reason, 8,000 P-1 centrifuges operating at 85% were dedicated to this task, it would take them about five months to enrich the helium. We can estimate the cost by assuming the operating expenses are the same and scaling the cost per SWU for uranium enrichment at $100 by a factor of 10 to give a total cost of $630,000 for the job. On the other hand, if political considerations made it advisable not to scale the SWU cost, the whole job would only cost $6.3 million.

If the overall SWU requirement for He-3 is much greater than for natural uranium enrichment, the required feed stock is also greatly increased. To supply the 1,400 detectors envisioned by DHS would, according to the assumptions made in the last post, require 130 kg of He-3. This, in turn, implies a feed stock of 820 tons of “natural” helium. (For some reason, people who deal with gases like to deal in cubic feet. A funny volume-sounding unit that actually conveys a mass since a standard pressure and temperature are understood. Eight hundred twenty tons of helium corresponds to nearly 18 million cubic feet.) That is large but should be placed in some sort of perspective by comparing it to other large users of helium. The Kennedy Space Center, for instance, uses 72 million cubic feet of helium each year, or four times DHS’s one-time use.

Most of the world’s helium comes from area around Amarillo, Texas, which has been estimated to contain 70 million tons of helium (I can hardly bring myself to continue using cubic feet, but if you want to know that number: Texas contains 32 billion cubic feet of helium.) Of course, if a single user uses 0.2% of the world’s supply of helium each, we might really be facing a shortfall in a short time. As more users of He-3 arise, it might be a good idea to remove that isotope from natural helium as a standard operating procedure.

A Modest Proposal

Iran appears to be coming less and less likely to compromise on its nuclear programs and to insist on more and more enrichment on Iranian soil. However, I think it might still be possible to arrange a multinationally owned enrichment center in Iran. Our proposal has always counted on shutting down Iranian centrifuges as more cost effective Western centrifuges come on line at the facility. However, that becomes less and less practical, from a purely economic point of view, as more and more Iranian centrifuges are brought on line. Why not, in the context of the multinational enrichment venture, dedicate Iranian centrifuges to enriching He-3? Thus, the 8,000 existing Iranian centrifuges would become an important specialty shop with a guaranteed customer if the US decided to only use depleted helium at, for instance, the Kennedy Space Center?

This proposal is, admittedly, based on back-of-the-envelop calculations that show that centrifuge enriching of helium three is possible. A real centrifuge expert should be contacted to try to understand why URENCO does not consider helium suitable for enrichment and, if it is, to do a real cost analysis. But right now, it seems like a good solution to me!

Note: This post has been delayed because I’m “stuck” in the Florida Keys and there has been a wide-area internet failure down here until very recently. It’s a dirty job but somebody has got to do it!

Noted Added: Scott Kemp points out that the reason centrifuges arent used to enrich helium is because the relative scale height—the scale at which the gas falls off in density as a function of distance from the inner rotor surface—of helium is much, much greater than for a heavy gas like UF6. In order to get an efficient centrifuge separation, the diameter would need to be much, much greater than for uranium. Thanks Scott! This difference in scaling height results in a much decreased density of the helium near the rotor surface. That explains the erroneous results. By the way, this is an interesting example of how some scaling properties (i.e. equation 3 of the Review of Centrifuges paper) can be badly misapplied in “back-of-the-envelop” calculations if the underlying physics is not fully considered.

I don’t believe this scheme will work. The Zippes run hot resulting in an unacceptable loss rate for the helium as well as the potential for material fatigue caused by helium impregnation/outgassing cycles. If you were intent on using centrifuges a need would present itself for a uniquely engineered cryo-centrifuge. Iran’s IR-1,2,3+ are not up to the task of separating helium, no current Zippe design could handle hot helium. It’s again far more economic and proven to utilize low temperature rectification for enrichment of helium, which exhibits a superfluid regime that lends itself to convenient isotope separation.

I am confused about what a centrifuge to do this would look like. The rotor is now running subsonic since the speed of sound in helium is 1000 m/s instead of 100 m/s in UF6. Meanwhile, the pressure ratio between the axis and the rim is only like 1.5x instead of thousands of times. Momentum transport by the pickup scoops and any axial piping seems like it is a huge issue now. So, I don’t see how the countercurrent principle is going to work.

If not, it seems like the centrifuge is just a spinning tube with a tiny inlet at the top center and a similar outlet at the bottom . . . and then the rotor could be designed to leak . . . maybe? Then I can’t pump out the vacuum jacket though. But moreover, without the countercurrent, the maximum enrichment per stage would only be like 10% – implying like over a hundred rotors in series to get to 95% enrichment. Now, it doesn’t so much look like a cascade at all, just a series connection.

Now, the diffusivity of helium should be on the order of a few cm^2/sec, so the residence time in any reasonably sized rotor is going to need to be tens of seconds at least, if not more – say 10 sec. But, I’ve got to flow 18 million(STP) cubic feet through the thing in a year. That means the rotor has to have a volume of 6 cu ft/pressure(atm) >~ 1 cu ft at 100 psi helium pressure. A rotor 10 cm in diameter would have to be 12 feet long. I can jack the pressure, but only so far before the rotor has to get thicker just to hold off the centrifugal pressure of the gas . . .

I mean this just seems like a whole world of a different thing. And, how much money does it cost to develop a new centrifuge, anyway?

How about we do it thermoacoustically?

SEE:

http://www.lanl.gov/thermoacoustics/Pubs/JASA02efficiency.pdf

Unless I’m mistaken, purification of helium from air is already done by liquefying it, since everything else freezes out before you get to 4.2K, the liquid temperature at 1 bar (atmosphere). By pumping it to about 1 mbar, you can cool to about 1.3K. At that temperature, the vapor pressure of He-3 is already a factor of 20 greater than that of He-4. But given a very low ratio of He-3 to He-4, I expect that most of what you would pump out would still be He-4 unless further cooling power were being supplied from somewhere. That can be supplied by a dilution refrigerator operating at a few hundred mK. At 600 mK, the vapor pressure of He-3 will be 0.7 mbar, while that of He-4 will be at least 1000 times lower. So you will need just a few stages of distillation at this temperature (e.g. evaporation, sucking the enriched mix up to room temp through heat exchangers, compressing it and sending it back down through the heat exchangers for another round) to take your 250 ppm to around 10% He-3, after which you could also take advantage of the liquid phase separation, or use a conventional low-temperature rectification column to finish the job.

Well, according to this document,

http://fti.neep.wisc.edu/pdf/fdm967.pdf , the way the first stage of enrichment, from ~0.2 ppm, not 200 ppm, to about 1%, would likely be done is with a “superfluid/superleak” method. At 2K and below, He-4 is superfluid and will pass through microscopic pores that will block the H-3 atoms. After 1%, further enrichment can be done by distillation, without need of temperatures lower than 1.6K. It turns out that the energy cost of this process is low compared with that of separating the raw helium from methane and other gases. So, not only are centrifuges not the best solution, they would not even solve the right problem.

The isotopic composition of helium reservoirs (natural gas deposits) is not the same as air and highly variable (50 ppb to 1 ppm), depending on the geologic conditions. This represents another few orders of magnitude problem with the calculations.

It’s not economical to extract helium out of air. It’s certainly not economical to extract He-3 out of air.