click on the image for a larger version

R is the number of secondary cases caused by each infected person; thus R=1.1 means for each ten people sick, one more person will come down with the disease they will transmit it to 11 other people; R=3 means that each infected person transmits it to three others.

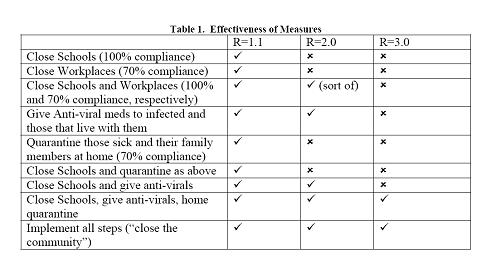

To say that the required response to a pandemic depends on its virulence is, of course, like saying rain depends on clouds. However, there have been a number of interesting simulations that do show which measures are effective and which are not at various levels of virulence. I’m using just one group of papers by one set of authors ( Roberts, Baker, Jennings, Sertsou, and Wilson ) to examine this issue so it’s likely that there are other results that might lead to different conclusions. (These papers are also for isolated communities, like New Zealand, that have only a single introduction of the disease so large countries with multiple entry points might respond differently.) Nevertheless, it is interesting to see which measures are effective and which are not.

For a relatively non-virulent strains (i.e. does not rabidly infect others), relatively benign measures would work. Unfortunately, relatively non-virulent strains last longer: the model I’m talking about predicts that if R=1.1, it would take 600 days for the epidemic to run its course if no preventative steps are taken. A very virulent strain, where each sick person infects three others, would burn through the population in 80 days. Closing schools, one of the first thing any parent thinks about, could have a significant social impact if the disease ran that long of a course. On the other hand, it is very effective to simply treat sick people and the people who live in the same house with antiviral meds such as tamiflu. It would also seem that only in the most virulent outbreaks do we need to even quarantine those people in their homes. Which is probably good since that doesn’t seem to have a very high compliance rate (it was assumed in the study that 70% of the people complied with it). Try quarantining some of those folks who refuse to pay their taxes because they don’t believe the constitution gives the government that right!

It really seems that antiviral meds, if effective, are the big difference between now and 1918. However, we don’t need to stockpile enough doses for everyone in the nation, only those sick and those living with them. Mexico City has, both by decree (closing schools and churches) and common consent (avoiding museums etc.), implemented very wide ranging quarantine measures. But do they have antiviral meds? If not, the United States should, out of its own interest, start sharing those meds with Mexico. It would seem that they wouldn’t need very much.

Of course, there are questions about how effective antiviral meds are with a report in the Los Angles Times that Tamiflu is not as effective against N1H1 strains as some older meds. This is another important issue to be settled as soon as possible. (Please note I am NOT suggesting shipping Tamiflu to Mexico as a way of testing its effectiveness. Effective antiviral meds to Mexico is an important public health initiative and not a laboratory study.) If antiviral meds are NOT effective, then public health measures are going to have to have significant social impact for extended periods of time if the virus is more virulent than the R=1.1 case shown here.

Something is wrong with your R calculation. If R=1.1 means that for every ten sick people one more will get infected, that means that if R=1, for every sick person no more will be infected. It follows then that if R=2 one more person is infected for every infected person, and R=3 means two more infected. You say that R=3 means three more are infected. I’m guessing that’s right and your R=1.1 calculation is wrong, because otherwise the R values between 0 and 1 would be meaningless. Can you check those again?

So this R number is actually pretty subtle and not a little (to me) confusing. I spent some time trying to educate myself on disease transmission and found this primer that helped clarify things.

Yes, the statement w/r/t transmissibility or basic reproductive measure, R0 of 1.1 infecting 11 people is incorrect.

An R0 of 1.1 indicates that statistically, each infected person infects 1.1 other people.

Until we have better data on the denominator, R0’s for the current swine flu are speculative.

Defined as the average number of secondary cases produced by one infectious individual in a population in which everyone is susceptible, secondary transmission rates are a measure of how contagious a disease is in a particular setting. If R0 = 1 then one infected person will infect one other. If R0 = 10, then one infected person will infect ten people, and an outbreak spreads more quickly to a larger population. An R0 < 1 is considered indicative of an outbreak that is under control. An R0 close to 1 is frequently interpreted as indicating that a disease spreads predominantly via close personal contacts, as in a non-quarantined hospital setting or care by a family member. An R0 > 1 is regarded as signifying a spreading outbreak. Sophisticated modeling of secondary transmission rates can care about the effect of outbreak controls and vaccine-induced immunity.

For comparison, the R0 for 1957-1958 pandemic “Asian flu” A (H2N2), in communities/instances with no vaccine, was 1.7. (Ira M. Longini, Jr., M. Elizabeth Halloran, Azhar Nizam and Yang Yang, “Containing Pandemic Influenza with Antiviral Agents,” Am. J. Epidemiol., 2004, vol. 159, pp. 623-633).

Measles has one of the highest R0’s observed historically, up to 40 (Ottar N. Njornstad, Barbel F. Finkenstadt, and Bryan T. Grenfell, “Dynamics of Measles Epidemics: Estimating Scaling of Transmission Rates Using a Time Series SIR Model,” Ecol. Mono., 2002, vol. 72, pp. 169-184.) But with modern medicine and robust public health, R0 of measles is estimated to vary from 14-18 (Roy Anderson and Robert May, “Population Biology of Infectious Diseases,” Nature, 1979, vol. 280, pp. 361-367, found in Njornstad, Finkenstadt and Grenfell.)

Margaret,

What I actually wrote is that is that for R=1.1, 10 people will infect 11, which I thought would be more understandable to people than saying 1 person infects 1.1 people. But I guess I was wrong about that.

Thanks for the clarification in your original post.

From the CDC Morbidity and Mortality mailing list

——————————-

As of April 28, 2009, viruses from 13 (20%) of 64 patients in the United States infected with swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus (S-OIV) have been tested for resistance to antiviral medications. To date, all tested viruses are resistant to amantadine and rimantadine but are susceptible to oseltamivir and zanamivir. This report provides detailed information on the drug susceptibility of the newly detected S-OIVs, which will aid in making recommendations for treatment and prophylaxis for S-OIV infection and will contribute

to antiviral-resistance monitoring and diagnostic test development.

——————————-

So it sounds like it’s treatable anyways.