click on the image for a larger version

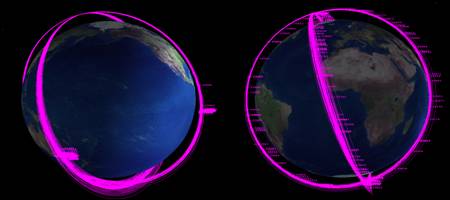

The image on the left shows the positions of the space debris 30 minutes after the collision while the image on the right shows them roughly 10 days later (now, as I write this)

I’m not going to do this every time a new batch of debris from the Iridium/Cosmos collision is cataloged but this shows something interesting.

As of Friday, February 20, 2009, there were 212 pieces of debris from that collision cataloged (144 associated with the Cosmos satellite and 68 with Iridium). Both groups of debris are starting to spread out along their initial satellite trajectories. And this is just the first pieces that have separated from the swarm. As time goes by, the rest of the debris pieces in the swarm will start to separate and fill in these “tubes” of debris.

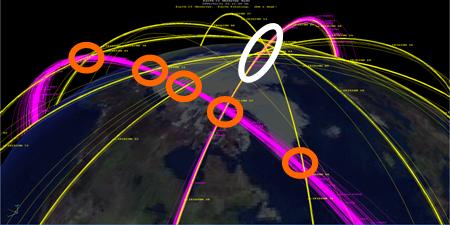

The debris from all this collision will, of course, threaten all the satellites at this most popular of altitudes but it does threaten Iridium satellites the most. Take a look at the picture below, which shows where Iridium orbits cross the debris tubes near the North Pole. Actually, all the Iridium satellites pass through both debris tubes twice per orbit. That’s four times of dramatically increased chances of another collision (this time between a satellite and a piece of debris) every 100 minutes, roughly. Of course, as time goes by, the debris will spread out of the tube because of natural orbital motion and spread more uniformly across the face of the Earth. Unfortunately, this does not reduce the chances of another Iridium satellite being hit; it just makes it a sort of continuous danger.

click on the image for a larger version

The Iridium satellites are shown in yellow and the pieces of space debris from the collision are shown in magenta. The white circle shows an area of Iridium crossings of the Iridium 33 debris above the North Pole while the red circles highlight the places were Iridium satellites cross the debris tube of the Cosmos 2251 satellite

Avoiding space debris is a financial issue. It costs money to move your satellite (counted either by paying for the launch of more mass—the fuel—or by a decreased lifetime of the satellite). But Iridium (and other satellites) is going to have to live through a long period (10 years? At the minimum would be my guess) of increased danger. How much is that worth to Iridium? Would it be worth the cost of moving one of its satellites every week? That’s probably what it would take avoid coming within 800 meters of some piece of space debris. So Perhaps its not worth it. But then again, being hit by a piece of space debris is not going to create the thousands (tens of thousands?) of pieces of debris that satellite-on-satellite collisions create. So maybe we can live with that. (But lets see a study that simulates the number of pieces of debris created in a satellite/space-junk collision vs. the fuel costs.) It is certainly worth moving a satellite to avoid hitting another, massive satellite. Is it worth paying for the fuel—and by that I mean paying for the mass penalty at launch—to de-orbit a satellite near the end of its lifetime? After this collision, I hope more people agree with me that it is.

On a purely techno-wonk subject: there is no indication that pieces of debris were given extremely high velocities in this collision the way they were with both the Chinese 2007 ASAT test and the USA-193 shoot-down. I’m becoming more and more convinced that is only possible for near-head-on collisions. I explained the kinematics of this phenomena in a preliminary analysis of that ASAT test and Prof. Andrew Higgins explained its dynamics by examining the shockwaves produced. Perhaps this mechanism’s absence in most collisions (which are not head-on) partially explains why NASA’s debris models did not predict the extraordinary number of pieces created during the Chinese ASAT test?

Hello,

Could you please tell us those screen shots of Earth’s outer space you’re using come from which program ? thanks

I generated these images using Aerospace’s SOAP (Satellite Orbit Analysis Program). Which is, unfortunately, no longer supported or (I think) available.

Interesting. The Higgins analysis shows that my intuition about hypervelocity collisions being equivalent to a detonation that produces shock waves was essentially right.

The problem are not old satellites, the problem is behavior comparable to small children which believe things would remain the same.

Amount of satellites grows. A meteo could do the same damage, and then some because of hypervelocity collision, as an old satellite. ASAT would be also quite common because it’s advantageous to defender to deny recon assets to attacker.

Any countermeasures should be proactive. Badly tailored restrictions would only increase costs and bureaucracy. I recall an idea about a weak laser that was supposed to deorbit a debris by introduction of an additional drag. Thought a much better idea would be a powerful laser which would boil/vaporize debris. (Which basically means a weaponized space.) Satellites also should have higher resilience.

Any two objects at the same altitude will intersect one another’s trajectory twice per orbit. Why are the other Iridium sats at greater risk than everything else?

Anon, as you say “Any two objects at the same altitude will intersect one another’s trajectory twice per orbit.” But, of course, no two objects are ever at exactly the same altitude during their entire orbits. Not even Iridium satellites in the same orbital plane. Iridium satellites, however, are closer to the debris tubes (a term I use to emphasize that these debris swarms occupy a range in altitudes) than any other satellite constellation. And, of course, there are more Iridium satellites in their constellation than, say, sun-sync satellites which might have very close orbital altitudes. Of course, other satellites are in danger; just not quite as much.

Really nice Google Earth visualization of the debris here: http://orbitingfrog.com/blog/2009/02/19/tracking-the-remains-of-iridium-33-and-cosmos-2251/