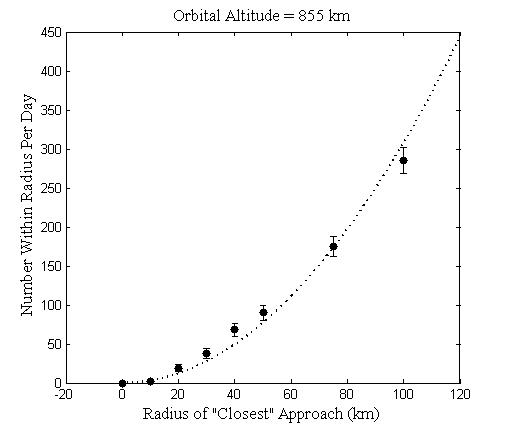

Jeffrey writes in his recent post about BX-1 being a Rorschach test and he appears to be right on so many levels. I thought I’d riff off of his excellent post and focus in on one aspect that has been bothering me for quite a while: defining what maneuvering actually means. You see, space isn’t so big or empty as many of us think it is and that has a lot of implications. Certainly I thought it was much bigger and emptier than it really is until I made this plot:

This plot shows how often a cataloged object comes within a given distance of a hypothetical equatorial satellite at an altitude of 855 km. The dotted line shows how this would increase purely with cross sectional area (R^2).

It turns out that satellites pass fairly close to something fairly often and often that something is a functioning satellite. Now this plot is for a hypothetical satellite with a circular orbit at an altitude of 855 km, very close to the most popular orbital altitude. (Its also the altitude of the FY-1C China shot down in January 2007, which is why I made this plot.) But it shows that such a satellite passes within 45 km of a cataloged object about once every half hour. Several of these each day are functioning satellites so if we are concerned about passing close to the ISS, perhaps one “rule of the road” should be that some orbital altitude bands should be reserved for human activity. That seems to me to be the only way of reducing this sort of fly-by. On the other hand, China’s BX-1 was released as part of a manned mission so perhaps even that incident wouldn’t have been regulated.

If, on the other hand, we are concerned about countries developing their ASAT capabilities by testing ASAT components on other satellites (such as trackers or guidance systems) we cannot simply say: don’t come within such and such a distance! That’s simply not practical since satellites come within very close distances of something quite often. Instead, we need to add something to make a practical rule. I proposed a ban on actual maneuvering near another object, say within 100 km; something that happens every 5 minutes at 855 km altitude. By that, I meant actually accelerating away from the initial Keplerian orbit. Of course, even that would be difficult to time even by a country that was intent on obeying the rules so perhaps you need to introduce yet another requirement, say, an object greater than such-and-such apparent magnitude or size. As you can see, things quickly get very complicated because space is neither as big or as empty as we like to think.

This very informative data shows how little would be accomplished by any reasonable prescription of minimum flyby distances, or even your proposal to ban acceleration during close flybys. After all, the divert thrusters and homing sensors of an ASAT weapon can be tested independently of each other, and signatures of target satellites can be acquired at various ranges and angles and under various lighting conditions over the course of months and years of flybys.

This leads again to the conclusion that restraining the ASAT race will require 1) formally banning ASAT development, testing, and deployment, and 2) requiring states to account for the capabilities, numbers, costs and purposes of vehicles which appear to be ASAT-capable, and any tests of such vehicles which appear to be defacto ASAT tests.

The usual argument against the practicality of space arms control is that the issues are too complex and ambiguous to allow the writing of a treaty that will ban everything that needs to be banned while allowing everything that is desirable to allow.

However, it is not that hard to describe what ASAT development and testing would look like, and what would distinguish it from peaceful use of similiar technologies. What is needed, in order to make such regulation feasible, is a regulatory body, similar to the IAEA, capable of independent investigation into ambiguous cases, and of reporting its findings to the Security Council.

Thanks Geoff. This is an exceptionally useful back of the envelope calculation that appears to show that what happened with the SZ7-ISS is not at all extraordinary, which is probably why NASA was not concerned about the proximity, which I would assume is not that much different than prior SZ missions?