Introduction

This is the second in a series of blog posts I’m writing on True Promise II, the October 2024 Iranian missile attack against Israel. This post focuses on the U.S. and Israeli missile defense efforts, building on my previous post on TP II as well as the work and methodology outlined by Steve Fetter and David Wright in their excellent recent article in The Washington Quarterly. I’d encourage everyone to read it. While there are some slight differences between the numbers I arrive at and those of Fetter and Wright, the differences are slight and do not challenge any of Fetter and Wright’s conclusions. In fact, my replication of their results strengthens their conclusion that the Israeli anti-ballistic missile (ABM) effort during True Promise II was a successful but highly difficult undertaking not replicable in different contexts, such as defending the continental United States.

Similar to my analysis of the ABM launches during the 12 Day War, this piece relies on a video taken by Jordanian photographer Zaid al-Abbadi from a suburb of Amman. Facing west towards Israel and the Mediterranean, Abbadi captured Israeli Arrow-3 interceptors flying east out over the camera to attempt intercepts over Jordan, behind the camera.

The Arrow-3 is an exoatmospheric midcourse interceptor, attacking ballistic missiles in space after their boosters have finished firing but before they enter the terminal phase and reenter the atmosphere towards their targets. Arrow-3 constitutes the upper tier of the layered Israeli ABM system. The middle layer of the system consists of the Arrow-2, a high altitude interceptor with a range of about 90 km, though reports vary. The lower layer is made up of the Stunner interceptor used by the David’s Sling air defense system, which has a peculiar “dolphin” shaped nose designed to pack in additional sensors.

Some time after the Arrow-3s launched, the Iranian missiles which survived the midcourse phase arrived, descending towards their targets across Israel to be engaged by the Israeli ABM underlayer.

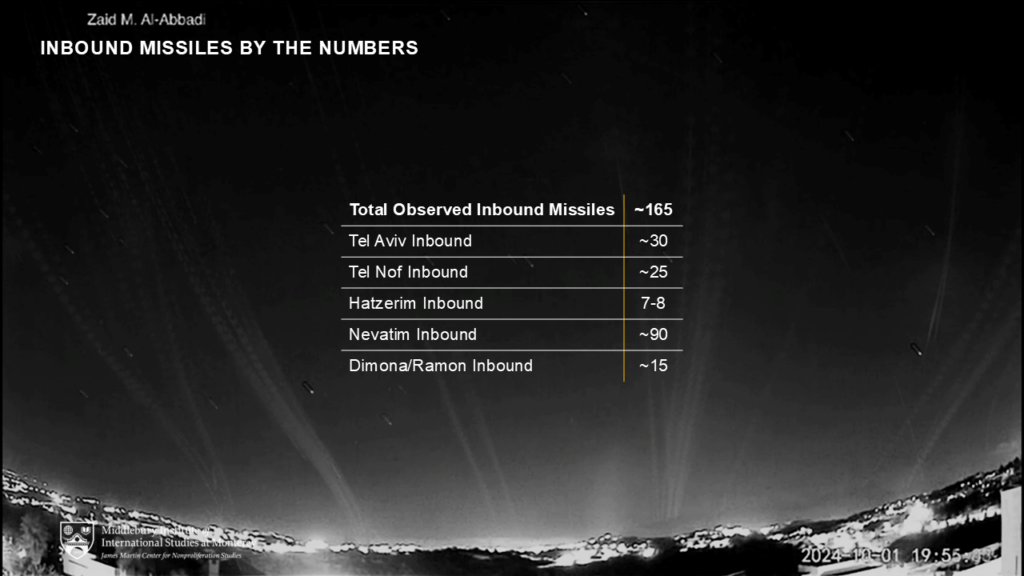

Two key pieces of information are derived from examining the video. First, Israel fired 18 interceptors from four sites. Second, 165 Iranian missiles targeted at five different areas across Israel survived midcourse. This information, combined with the data Fetter and Wright collected on the number and distribution of missile impact points across Israel, helps paint a holistic picture of the effectiveness of U.S. and Israeli ABM efforts.

Midcourse Phase Intercepts

Based on my analysis of the video, 18 Arrow-3 interceptors were fired from a number of ABM sites across Israel. The Arrow-3s can be identified as the video shows the first stage burning out and the second stage igniting shortly thereafter.

| Nevatim | Sdot Micha/Palmachim | Tel Aviv | Total | |

| Arrow-3s | 5 | 5 | 8 | 18 |

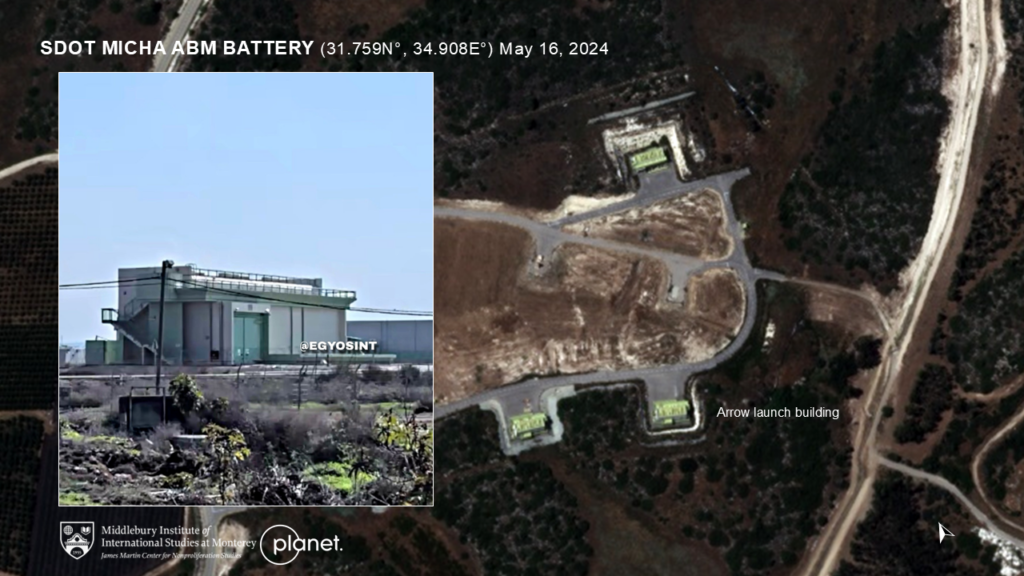

These numbers and sites match with known Israeli ABM sites.

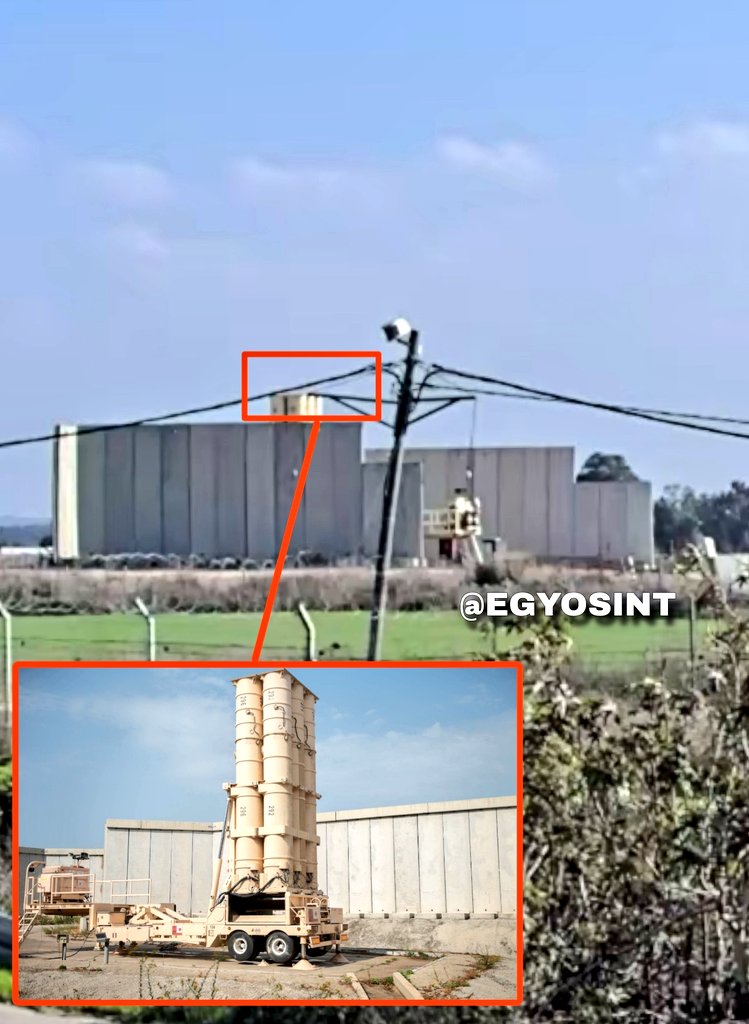

Some of these sites have revetments or mobile walls for mobile Arrow launchers, such as Palmachim and Nevatim.

Other Israeli ABM sites, like Sdot Micha and Ein Shemer, have dedicated launch buildings for the Arrow-3 interceptors.

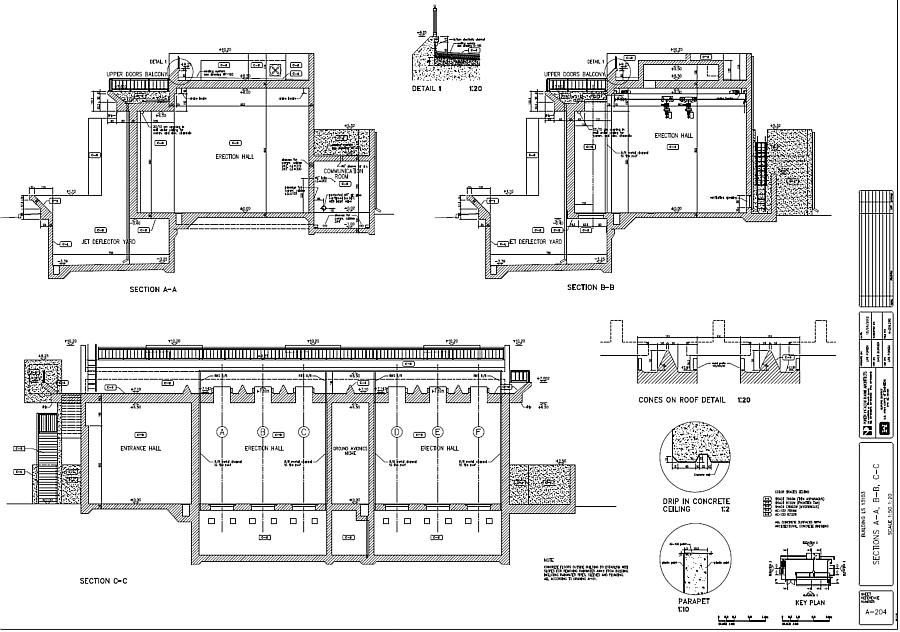

Internal photos of the buildings show how the six Arrow-3 canisters are arranged in each building.

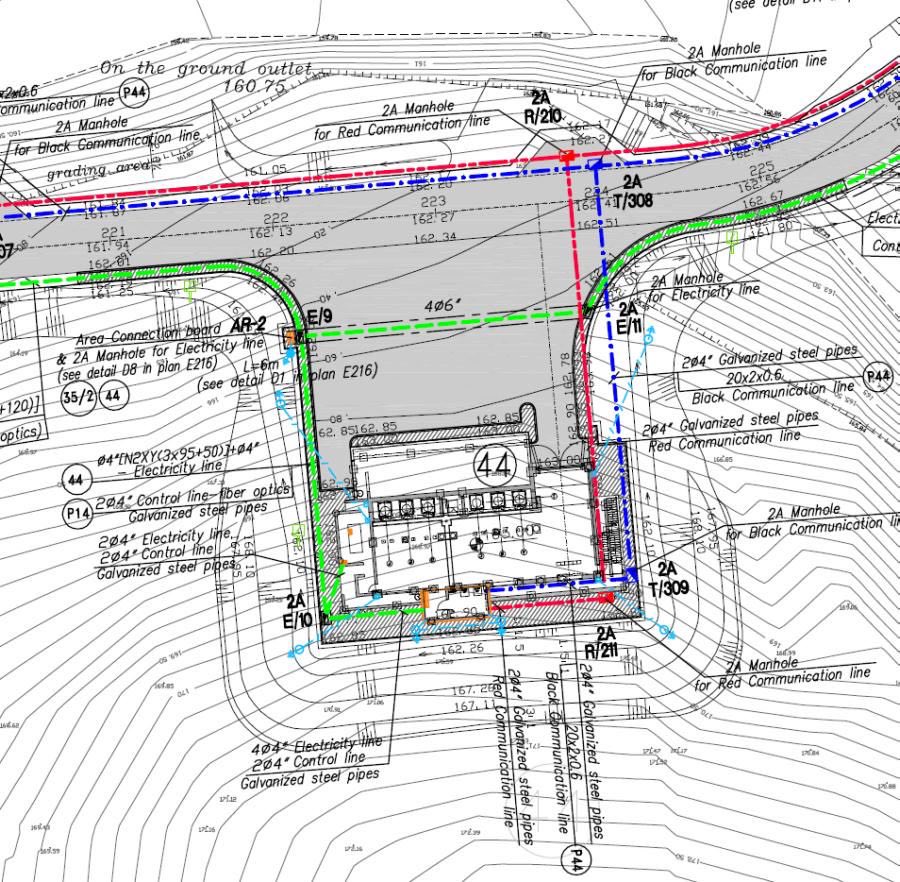

A U.S. Army Corps of Engineers document soliciting bids to construct the launchers in Israel leaked back in 2013, including diagrams of the launcher buildings.

Arrow-3s firing from these static and mobile launchers across Israel made up the majority of the long-range interceptors during the Iranian missile strike.

Additionally, the U.S. Navy claimed to have “fired a dozen interceptors” and “destroyed a handful of Iranian missiles using a combination of weapons, including the Standard Missile 3.” The SM-3 is another midcourse interceptor with a kinetic kill vehicle. Based on a video released on DVIDS at least one SM-3 IB was used. The IB can be distinguished from the IIA as the IIA has a uniform width between the body of the interceptor and the booster, while the body of the IB is skinnier than the booster.

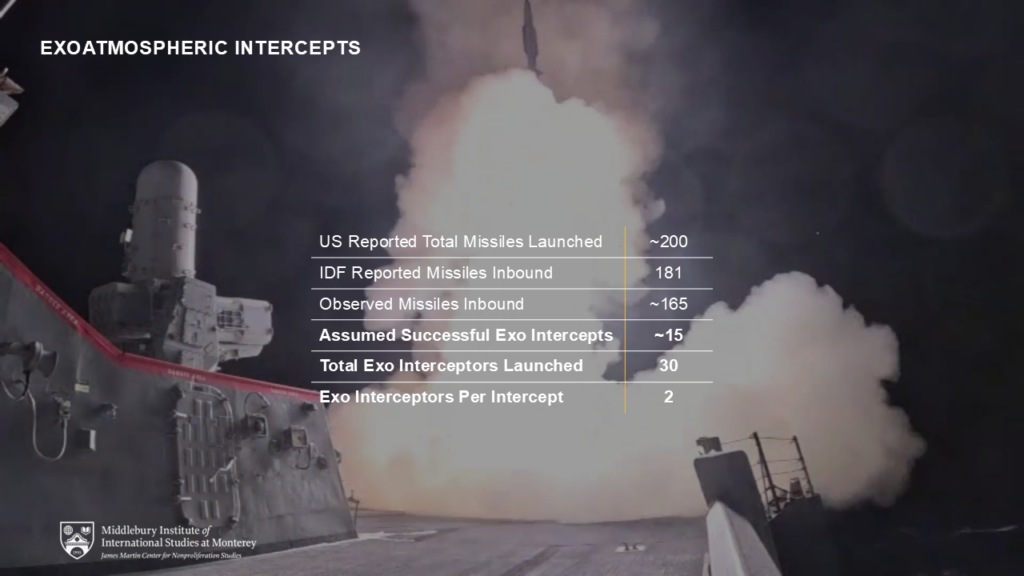

I believe the SM-3 launches were not captured in Abbadi’s video as those would have been from U.S. naval vessels in the Mediterranean, likely too far away to be captured in Jordan. Moreover, all the long-range launches recorded in the Abbadi video align nicely with ABM sites in Israel. This suggests that altogether 30 midcourse interceptors were fired during the Iranian attack.

But how effective were these interceptors? The U.S. Navy claimed “a handful” of intercepts, which isn’t the most precise term in the world. I interpret this to mean somewhere around 4-6 intercepts from the 12 Navy interceptors fired. The Abbadi video can be used to complement the Navy statement and make a more comprehensive assessment of exoatmospheric intercepts.

Recapping my last post, the Iranians launched 200 missiles, of which 20 failed during boost, leaving 180 missiles which entered the midcourse phase of missile flight and were detected by Israeli early warning radars.

By stacking frames of the Abbadi video, we can see the various Iranian targets and determine which areas were the focus of the missile attack.

Upon examination of the Abbadi video, it appears 165 Iranian missiles survived midcourse and went on to roughly five target areas; Dimona/Ramon AFB (its unclear), Nevatim, Hatzerim AFB, Tel Nof, AFB and Tel Aviv.

By subtracting the observed 165 inbound missiles from the 180 missiles detected by the Israelis, we get the number of Iranian missiles which were either intercepted or failed during the midcourse phase of flight; 15. I assume all 15 were the result of interception to be generous to the defense, but it is possible some failed and the intercept rate is lower than I calculate. Of those 15 intercepts, 4-6 of them were U.S. Navy, so the other 11-9 are Israeli.

30 intercepts for 15 interceptors. While this initially seems like a 50% intercept rate, that may not be correct. The defenders may have been practicing 2-on-1 targeting, assigning two interceptors to each inbound missile they target. In that case the intercept rate would be 100%, while the single shot probability of kill per interceptor would be lower. In that scenario 18 Arrow-3s targeted 9 Iranian missiles and hit all of them, while the 12 U.S. interceptors targeted and hit 6 Iranian missiles. My guess is the 2-on-1 targeting scenario is more likely, but that is a genuine guess. What is clear from the data is 30 interceptors were fired and 15 fewer Iranian missiles entered Israeli airspace than were detected.

Terminal Phase Intercepts

Now that we have a sense of how the upper layer of Israeli and U.S. interceptors performed, let’s turn to the lower layer; the terminal phase defenses like Arrow-2 and the Stunner used by David’s Sling.

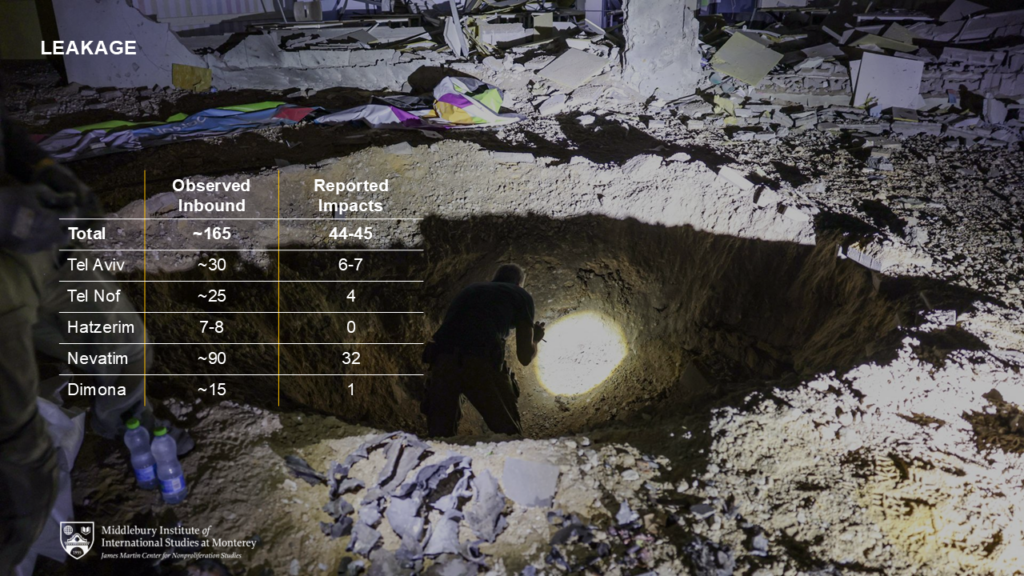

Combining the number of missiles which survived midcourse with data Fetter and Wright collected on missile impact sites in Israel, we can determine the effectiveness of terminal phase Israel defenses.

One note is that in the Abbadi video there are often bright flashes as the Iranian missiles are heading towards their targets. Those flashes may just be the reentry vehicles heating up during reentry, but they could also be Iranian missiles failing during reentry and breaking up. It is hard to distinguish based on the video, so I am assuming none of the Iranian missiles failed during reentry, making this assessment generous to both the reliability of the Iranian missiles and the effectiveness of the Israeli defenses.

The only divergence in my account of the number of impacts in Tel Aviv from that of Fetter and Wright is the inclusion of one downrange miss near Mossad HQ. This impact was not reported in the media as it landed in the Mediterranean Sea and therefore did not cause any damage, but is visible in videos posted to social media. This inclusion produces a small change in the effectiveness rate on the order of about 2-3%.

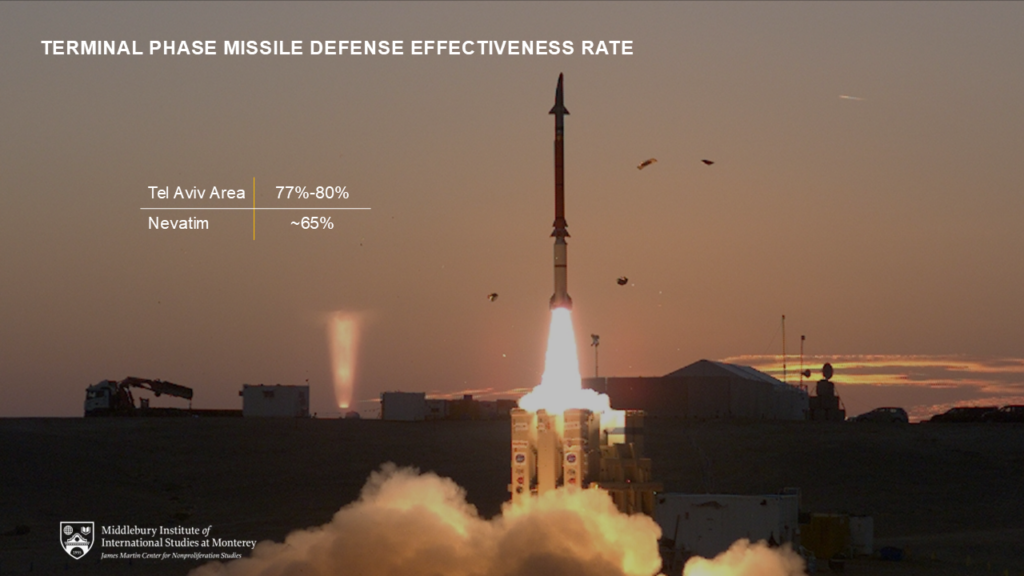

I use a similar method to that Fetter and Wright used to calculate the effectiveness of terminal phase defenses in the Tel Aviv area using my data on inbound missiles. By taking the number of missile impacts and dividing it by the number of observed inbound missiles in the terminal phase, we can derive the effectiveness rate of the terminal layer. I have broken this up by target, focusing on Nevatim and the greater Tel Aviv area. That area includes Tel Aviv and Tel Nof, as the airbase is located in the southern part of the city.

A much-espoused quality of Iron Dome is that it can predict whether an incoming rocket will impact in a populated or unpopulated area, and selectively target those projectiles which will do the most damage. While it is unclear whether similar analytics were applied to the faster-moving ballistic missile threat, which included missiles maneuvering in the terminal phase, that feature of the system would complicate the analysis. Therefore, Fetter and Wright argue the Tel Aviv area would be the best representation of overall Israeli ABM effectiveness. It is the most densely populated area so the system would likely attempt to engage every incoming shot. This feature of the Israeli ABM system may explain the difference in effectiveness between Tel Aviv and Nevatim. Similarly, Israel may have chosen to not contest the missile attack against Nevatim as vigorously since it was not a densely-packed urban area, but a large airbase with open spaces where impacts would generate relatively little damage.

Another plausible explanation for the lower intercept rate at Nevatim is the oversaturation of defenses at Nevatim. Defenses there faced significantly more inbound missiles than any other part of the country, perhaps overwhelming the battle management system and depleting the interceptor magazine. Indeed, if the Israelis chose not to contest the attack as fiercely that reinforces the conclusion that the defenses were oversaturated. Ultimately, while I have included the Nevatim effectiveness estimate since it has not been estimated elsewhere, the Tel Aviv estimate is likely a better reflection of the true effectiveness of the Israeli ABM system.

Conclusions and Implications

There are two key takeaways from this analysis, both illustrating the difficulty of attempting to extrapolate the success of the missile defense of Israel during True Promise II to other contexts, such as the defense of the continental U.S. or Guam. First is the implications of the exoatmospheric interceptor expenditure and intercept rates. That the defense needed 30 expensive exoatmospheric interceptors to defeat 15 Iranian MRBMs speaks to the difficulty of midcourse interception even under favorable conditions. The midcourse interceptors attrited less than 10% of the inbound Iranian missile raid. Remember this is a generous estimate as some of those 15 Iranian missiles which do not arrive in the terminal phase may have failed during flight, and were not intercepted.

Even if the U.S. and Israel were practicing two-on-one targeting or attempting something like a shoot-look-shoot firing strategy, it is apparent from True Promise II that larger missile raids could easily overwhelm the defenses. While two-on-one targeting increases the chance of intercept, it also moves the defense further to the wrong side of the cost curve. Estimating the cost of SM-3 rounds is tricky given the different variants and price fluctuations. As only the cheaper and less advanced IB was observed in DVIDS videos, let’s assume only SM-3 Block IBs were fired against the Iranian missiles. Taking the approximately $8.8 million unit cost from when 40 IBs were being procured each year, it cost just under $18 million for two-on-one targeting for SM-3 against a single Iranian missile. The cost per Arrow-3 interceptor is unknown but is reported to be about $4 million each, thus two-on-one targeting for Arrow-3 is about $8 million for each Iranian missile. While the cost of Iranian missiles is murky and likely varies widely based on the specific model involved, it seems unlikely to me that they would be as expensive as the interceptors required for two-on-one targeting.

Whether the intercept rate was 50% or two interceptors were assigned to each missile so the engagement success rate was 100%, this experience underscores the difficulty of exoatmospheric ABM engagements and the ease with which those systems could be and have been oversaturated during a conflict. Moreover, it is unlikely the Iranian MRBMs were using countermeasures such as chaff, inflatable decoys, and radar jammers. The more basic threat clouds the Iranians generated and the U.S. and Israel faced during TP II were relatively easier to discriminate and allocate interceptors against than peer adversaries such as Russia or China.

The difficulty of midcourse defense brings me to the second takeaway; the Iranian saturation missile attack seems to have been effective. True Promise II was crafted to strain Israeli defenses much more effectively than True Promise I. Forgoing cruise missiles and drones in True Promise II meant that while the Israelis still had strategic warning of an Iranian attack thanks to Israeli and U.S. intelligence, they lacked the same kind of tactical warning which allowed them to ready defenses during True Promise I. Opting for larger numbers of more reliable ballistic missiles, coordinating launches so those missiles arrived in quick succession, and focusing fire on a few targets all helped the Iranians overcome Israeli defenses. The improvement is born out in the impact data. While there were only 9 or 10 missile impacts after True Promise I, there were about 45 after True Promise II. Moreover, the impact of saturation can be seen in the difference in intercept rate between Nevatim and the Tel Aviv area. Nevatim was targeted by about 50% of the missiles which survived midcourse, and that volume may have strained the defenses in the area, limiting local ABMs to a 65% effectiveness rate compared to the 80% effectiveness rate around Tel Aviv. While some of that leakage may be explained by the Israeli defenses preferentially targeting more threatening inbound missiles or choosing not to contest the attack, it is clear that the focused large volume fires against Nevatim meaningfully impacted Nevatim’s defenses and accounted for the majority of impacts against Israel during the operation.

Israeli ABM systems performed well against Iran during True Promise I and II. Yet, as Iran adapted its strikes, the Israeli system was placed under increasing stress. Careful analysis of videos, images, and impacts revealed the seams of the Israeli defensive effort during True Promise II, especially in midcourse and under focused coordinated fires. Under more pressure or in different contexts it is easy to see those seams rupturing, the defensive fabric of Guam or CONUS being handily oversaturated by larger raids consuming many midcourse interceptors and swamping terminal defenses. Additionally, these difficulties probably pushed the Israelis towards their aggressive missile defeat strategy during the June 2025 conflict. If the Israelis could not adequately weather raids of the volume of True Promise II or larger, they needed to take the fight to Iranian missile bases and launchers.