The “Would they? Could they?” debate in regard to nuclear terrorism is an old one. There has been a lot written about whether terrorists want to use nuclear weapons and, if they do, whether they have the technological capability to “make it so”.

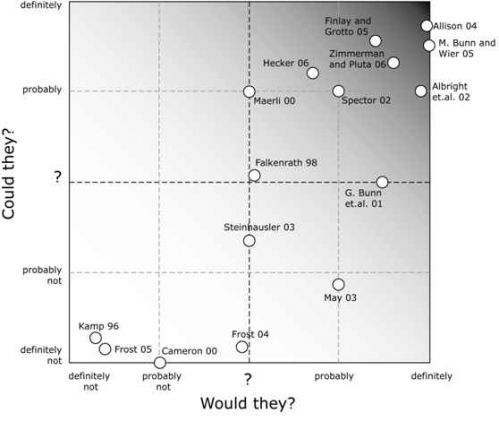

A PhD student at King’s, Simen Ellingsen, has come up with what I think is a rather clever way of summarising this debate: in the form of a graph (or, more accurately, a scatter plot). He has given me permission to reproduce this graph here (thanks, Simen).

Obviously, it’s slightly tongue in cheek but what Simen points out (and is worth taking note of) is the reasonably strong correlation. Generally, authors who think terrorists could, think they would (May being the exception).

It’s interesting to speculate about why this is. My guess is that those “terrorism experts” who don’t believe that terrorists want nukes, selectively present evidence that building nukes is hard. In contrast, those “technical experts” who think that building nukes isn’t so hard, tend to assume intent.

Anyway, Simen has an article coming out in next month’s Defense and Security Analysis, about the application of game theory to measures to counter nuclear terrorism, and it’s well worth a read.

Maybe the correlation is the inverse of what you said. Maybe those who think they would also tend to think they could. i.e. many think that where there’s a will there’s a way. Maybe?

I don’t see Levi on that chart but I’m guessing he would fall somewhere in the neutral to probably not area based on his book. I’m not familar with him beyond that recent text but he really didn’t get into the ‘would theys’ to any great extent (that I recall).

There also seems to be a positive correlation between the date of publication and prediction that they would/could. That is, authors of more recent publications seem to be more pessimistic…

Who is “they?” Terrorists are not equal in both capability and intent. Some groups (Al Qaeda) explicitly say they want such a capability, others not so much.

And what is “the technological capability to make it so” exactly? Produce nuclear material for a weapon? Create a weapon out of acquired material? And which material, uranium or plutonium?

So another explanation for the correlation may lie in such details.

Additionally, it’s interesting to note pre and post 9/11 assessments. Unfortunately, there are only 4 pre-9/11, but none are solidly in the upper-right quadrant and half (2) are in the lower left. Post-9/11, 7 are solidly upper-right and only one is lower-left. So another reason might be the psychological effect of 9/11.

One possible objection to an interesting and worthwhile chart is that the issue of intent is not analytically distinct from capability — in other words, terrorists might conclude that building a nuclear weapons is too expensive.

Do I want a large single-family home in Cleveland Park? Yes but not at current prices and my current income level.

Certainly in my article with PZ, I started from the assumption that Al Qaeda’s intent was suggested in how much they were willing to spend per death, then asked the question whether they (or another group) might be able to carry out such an attack on a cost-effective basis.

It all depends on the definitions. If “could they” means “is it possible that some group might succeed in pulling off an attack if it tried”, and “would they” means “will there actually be group that has a serious go at pulling off an attack”, then I may want to put myself (all alone) in the top left quadrant, way up on the y-axis and just left-of-center on the x-axis. The basic reason dovetail’s with Jeff’s comment — intent and capability aren’t independent. And what may matter most in determining intent is not the possibility of success in any attempt — which the chart captures — but rather the possibility of failure, which it doesn’t.

I haven’t seen the original text this is from, but I don’t think it’s accurate to describe Securing the Bomb 20005 (which I assume is the Bunn/Wier 05 piece referred to) as having as high a likelihood that terrorists could make a bomb as Allison 04, which makes a very alarming argument that it would be easy for them to do so. My basic position, which I’ve said there and elsewhere, is that making a nuclear bomb would be the most technically challenging thing a terrorist group has ever pulled off, but it’s a serious enough risk, given the immense consequences, that we should be worried enough to take further action to reduce the risk.

I remember the charts prepared by Dunn and Kahn regarding nuclear proliferation. Now that I look at them, I wonder what they had in mind when they prepared them. Game theory: Didn’t we use a lot of game theory during the Cold War? Specially in the field of nucler deterrence? I am not sure it was useful. I guess charts and game theory are interesting academic exercises.

1) A brute fact, due to organization problems and communication problems between and within the FBI and CIA, and lack of imagination and intelligence, 9/11 wasn´t stopped, a severe wake-up call, that started the 21st Century.

2) The HEU bomb, as well as the “dirty bomb” are more probable that terrorists actually would use against the US, than an actual nuclear weapon.

3) The HEU bomb, as outlined by nuclear physicists Thomas B. Cochran and Matthew G. McKinzie, in Scientific American, April 2008, pages 80-81:

“The ´quality´of nuclear material since then has continued to improve, however, so much so that 1987 Nobel laureate physicist and Manhattan Project scientist Luis Alvarez noted that if terrorists had modern weapons-grade uranium, they ´would have a good chance of setting off a high-yieled explosion simply by dropping one half of the material on the other half.´To test that assertion, we modeled the difference between the Little Boy design and an improvised nuclear device as crude as the one Alvarez described.

We again used the Los Alamos software code and modeled the yield of Little Boy on publicly available design information, as well as two simple configurations of HEU in a gun assembly. Our modeling showed that, for an explosive-driven gun assembly, the minimum quantity that was required to obtain a one-kiloton explosive yield would be substantially less than the amount of HEU in Little Boy. Most disturbingly, with larger quantities, a one-kiloton yield could be achieved with a probability greater than 50 percent by dropping a single piece of HEU onto another, confirming Alvarez´s statement. Designing an HEU bomb seems shockingly simple. The only real impediment, therefore, is secretly gathering sufficient material.”

@Anon,

Dirty bombs and crude nuclear weapons gets the press, but the much more easy to do threats are in bio-weapons that have been made possible by modern genetic engineering.

The basic raw materials and equipment for manipulating genes are widely available, and by and large, not tightly controlled.

It takes a certain amount of knowledge of the field to figure out what sort of super bugs you can and want to build, but that knowhow pool is expanding exponentially every year.

It is reasonable to assume that there is a growing set of simulation software to expedite and ease common tasks, making the creation of bio weapons easier and easier as software has done for other fields.

Would it be fair to say that the “minimum economic scale” for the misuse of these technologies are dropping across the board?

Just for the record, the anthrax mailer, to date, has not been apprehended.

I doubt the same can be said for future nuclear terrorists.

<em>The only real impediment, therefore, is secretly gathering sufficient material</em>

But however easy the rest is, it’s meaningless without getting hold of the nuclear material. It’s the critical path; whatever happens to the other processes involved, the availability of HEU or Pu governs the probability of a terrorist nuke.

And we know for a fact that nobody has yet secured significant illicit supplies; this suggests that it is very difficult. It really is a case of “first, catch your fish”.

Christhian – There was a lot of game theory back in the day—Schelling used it in a number of contexts—but there was a problem highlighted by a recent author (I forget which; probably Dan Ariely). Mathematicians such as John Nash were great proponents of game theory, but it generally requires the brain of a John Nash to produce much of use. It’s probably safe to say that few among us have one of those.

Matt Bunn hit the nail on the head. The reason we should worry about nuclear terrorism, regardless of the magnitude of the intent or the capability is because of the consequences. The risks caused by an event are the product of the probability of the event occuring and the consequences of the event. A low probability event with huge consequences is vital to worry about because of the consequences. This is particularly true in the nuclear terrorism case because, although we can do little to lower the consequences of a nuclear explosion (setting aside consequence management), we can do things to lower the probability of occurance. And, to the extent that the debate over the likelihood affects policy choices, this is the area that matters. What can we do to lower the probability (even if it is already relatively low), so that we can increase the probabiilty of avoiding the consequences?

There’s a public relations problem with this debate, exhibited recently by the Senate Gov Affairs and Homeland Security Committee. They held a hearing on the risks of nuclear terrorism. They wanted to talk about probability and consequences, but they didn’t want to hear anything about programs to mitigate the risk. They claimed they weren’t trying to whip up fears, but the politics of the situation argue differently. The hearing kind of fizzled, as none of the experts who testified (including Matt) would tell them that the evidence shows terrorists want, can aquire, and are well along the path to acquiring nuclear weapons (the staff initially wanted an independent review of the CIA data to demonstrate that the intelligence community was understating the threat of nuclear terrorism…). Further, the witnesses kept wandering off to make recommendations about how to reduce the risk. This all undermined the purpose of the hearing, which was to make people afraid without offering any remedies.

I believe that the axes should be swapped, and then the scatter-plot converted to a true dependency relationship i.e. we should really be interested in the shape of “would they” as a function of “could they”.

We know that the USA could, and did, in 1945. But since then all the existing nuclear weapons states have had about 10 – 60 years of “could” but “didn’t”; and this despite some pretty hairy near misses (think Kashmir conflicts, or Sino-Soviet border wars). Therefore it doesn’t seem to me that “would they” is always so strongly correlated with “could they” as the chart suggests.

Now I know that the chart refers to “terrorism”, and I’m talking about states, but in this field I really don’t believe that there is so much distinction. “Terrorism” as far as I am concerned often just boils down to demanding something, with a threat of violence if it’s not delivered. It could be the kid in the playground threatening to punch my lights out if I don’t give him my apple; it could be the Hillary Clinton offering to obliterate Iran if it makes a nuclear attack on Israel; it could be Osama bin Laden vowing to kill American soldiers if they don’t leave KSA. I’m not saying that the actions of states and “terrorists” are morally or legally equivalent (for the record, I happen to believe that they are not equivalent), but when it comes to a straightforward “Give me XXX, or else” then I think they can be compared. Which begs the question: Why do so many studies suggest that if terrorists could they would, while the only evidence we have shows that for about half a century multiple institutions could but didn’t?

For what it’s worth, my opinion is that the restraint on the use of nuclear weapons is driven by two factors:

1) Anonymity (or lack thereof). As we have all have experienced, if you are unlikely to be caught you are more likely to stray from the straight and narrow (hands up if you never pinched a few biscuits from mum’s jar when she wasn’t looking!), which is exactly where the game theorists come in with their Mutually Assured Destruction, and its variants. If a STATE launches an overt nuclear attack then it is fairly clear where it came from, and even if the attacked country were unable to retaliate it is possible / likely that its friends would do so (e.g. NATO). But if no-one knows who you are, or where you live, I believe you are much more likely to “go nuclear”.

2) Getting what you want. States are reluctant to go nuclear – except if their very existence is threatened – because in doing so they would lose in the court of world opinion, and ultimately lose whatever it is they went to war over in the first place. If China nuked Taiwan during some military conflict, I believe that world opinion would side with Taiwan. China might well take possession of the land, but if other countries cut off all trade links with China as a sanction (even at the expense of their own economies) it would be a useless victory. Similarly if ETA or the Tamil Tigers (or previously the Provisional IRA) had gone nuclear then they would have lost all moral claim to what they were fighting for. Unfortunately, though, some groups have no clear objective that they wish to retain at all costs. What, for example, does Al Qaeda want? It seems not to have any clearly defined objectives, and in truth is probably not anymore even a single group or ideology. Instead it looks more like a franchise for disaffected young men who want to make themselves feel important by dying in the process of killing someone else.

In short, I’d expect “would they” as a function of “could they” to bifurcate. At some time in the future some terrorists probably “could”, but will choose not to. These will be the groups that have well identified demands, and are in some way “identifiable” themselves e.g. through well known political wings and sympathisers (Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness spring to mind). Such groups are well known and have something to lose, so I’d expect them to act like states and to be similarly deterred (inasmuch as nuclear attacks can be deterred).

In contrast, there will be those who 100% would if they could. These will be the nihilists, the revengers, and those for whom death is actively welcomed (think crazy Christians – like David Koresh, jihadists, Aum Shin Riko, and the like). It could even be a lonely college student or disgruntled postal worker…

In the last case I don’t see any possibility for deterrence. Instead, as so clearly pointed out above, the only option is to rigourously restrict access to fissile materials.

Re: Hairs’ comment and some others.

The discussion of would they/could they should indeed start with identifying strategic goals and objectives of various types of terrorist groups and how a nuclear or radiological attack would serve their achievement. In this case, I think it would be pretty safe to not worry much about nationalist/separatist groups, left-wing, right-wing and other such (mostly secular) groups that have clear constituencies and more or less rational objectives.

This leaves us mostly with millenarian/apocalyptic groups (e.g. Aum Shinrikyo) and “global” groups such as Al Qaeda who would welcome total indiscriminate destruction. Then we can look closer at what they can do, and how capabilities and risks might affect their intent.

And concerning Al Qaeda’s goals, I think they’ve announced them pretty clearly in their “seven-stage” strategy. The war of attrition with the “far enemy” is the phase where the use of WMD seems to fit best.

All this being said, I remain skeptical of a nuclear terrorist attack any time soon.

It seems that given (1) the technological and material barriers to “could they” and (2) the resource expenditures necessary to reach an affirmative “could they,” then in order to progress to capability, the intent would need to be there as a precursor; hence the absence of data points in the upper left quadrant. By the same reasoning, however, I would question the data points falling on/near the upper half of the vertical axis for terrorist organizations.

I was in a seminar awhile back with people talking about the dangers of future developments bioengineering and nanoengineering, of the possible catastrophes that could be created once these technologies had gotten to the stage where you don’t have to do “science” anymore, when it all becomes an “engineering” problem.

At one point I was asked if I thought the history of nuclear weapons gave us any advice on this — at first I thought the answer was probably “no,” as the differences seemed pretty great. In some further refinement, I came up with the conclusion that nuclear weapons actually look much easier to control in comparison to these possible dangers.

After all, nuclear weapons require acquisition of special, rare, and esoterically processed materials more than they do knowledge, and said materials are relatively easy to regulate (compared to knowledge, which flits in and out all over the place all the time, and can even be squeezed out by the very efforts that were trying to control it). The means to produce the materials from scratch aren’t easy, and are relatively easy to notice, raising the level of risk in doing so. The most serious effort for terrorism would be to steal the materials, and while that’s not a problem you’ll ever remove completely, you could certainly make that pretty tough.

In comparison, the future bio- and nano- threats seem practically impossible to regulate — someday, not too long from now, the laboratory equipment to do that sort of thing will be able to be purchased off-the-shelf for a few thousand dollars at most. (Assuming, of course, we don’t at least try to regulate said machines quite closely. Which might be a good idea, though the scientists are naturally repulsed by the idea. Of course, whether you could even institute effective regulation at any level is one I don’t know the answer to, I imagine it would depend heavily on the future technical details of the specific apparatus required.)

The nuclear situation looks relatively benign, relatively preventable, from that point of view. The idea that we can “only” restrict access to fissile materials is actually quite reassuring, comparatively speaking — at least we can do that, in the sense that it is a technically realizable goal.

(I’m sure none of the above is terribly original, but anyway, it came to mind.)

The threat from bio weapons is more urgent, and takes a far less technical infrastructure.

The signals for manufacturing and transporting are far less observable.AQ may want to nuke the US, but it is still far beyond their reach.

CB isn’t.

According to VP Cheney, if we follow the “one per cent doctrine”, a one per cent chance of a terrorist using a nuclear weapon against a US city should be treated as a dead certainty given the consequences. Let us assume that the VP’s figure is correct.

Ian Bellany in Curbing the Spread of Nuclear Weapons cites a 1%-2% annual probability for an accidental nuclear launch in a nuclear weapons complex of 5 states.

So, (a) why isn’t the threat of accidental nuclear war out in the public domain as much as nuclear terrorism? (B) Why do intellectuals mostly focus on the latter and not the former?

© It is widely acknowledged that US strategic forces transformation, i.e. prompt global strike etc, actually increases the probability of accidental launch.

If we apply the “one percent doctrine” then it follows that arms control becomes the most important facet of global security. One might even argue that a militarised response to terrorism increases the incentives for Jihadi groups to make an attempt at nuke terror.

Who is to say that an Al Qeada device isn’t actually meant to deter the US not actually to be used?

Let us think of the terrorism problem strategically. Terrorists are revolutionary vanguards that seek to mobilise a disaffected but apathetic population. The main strategic objective achieved by a nuke terror event is to elicit a US nuclear response. To take that response completely off the table through declaratory policy would be a form of deterrence by denial.

Seeing as my informal chart has sparked quite an interesting debate I reckon it’s time I commented briefly. I won’t try to comment on everything that’s been said but limit myself to a few points of information. I originally made the chart just as a means to structure the existing literature for myself, and it should not be taken too seriously.

First of all: James forgot the references to go with the dots. I copied them in at the end of this post. I decided about halfway to only include articles (I think Finlay and Grotto is the exception), so ‘Bunn and Wier 05’ is the “Seven Myths” paper, not ‘Securing the Bomb 2005’. That’s part of the reason why Levi isn’t on there, but also because his excellent book was published after this chart was made and it hasn’t been updated since. Dr. Levi got the rare honour of placing his own dot in the diagramme 🙂 Note also that these references far from exhaust the literature, and I’ve only included papers that would fit in the diagramme at all and only one paper per author (except Frost, who changed his mind at some point)

As a general note the exact position of the dots is very rough and indeed, it’s probably impossible to devise stringent criteria by which all these papers could be compared in any rigorous and at the same time meaningful way along just two axes.

The project which the questions refer to is a terrorist attempt to build a nuclear device (as opposed to steal a finished one. Also as opposed to a radiological dispersion device). But the different papers have different approaches and ask slightly different questions, hence making the exact interpretation of “would” and “could” more rigorous doesn’t work.

I agree with Levi that “would” and “could” are not independent variables, but nor is there a linear relation between them. Notably, papers which hold that terrorists are incapable of building a device typically argue that they are uninterested for fairly independent reasons (particularly fear of alienating their audience). Levi wasn’t the first to think that fear of failure could well deter the rational terrorist from spending his limited funds on a nuclear project, but it hasn’t been a major point in most of the debate, and I think he is very right in emphasising it.

Anyways, here are the references:

Albright, Buehler & Higgins ‘Bin Laden and the bomb’ Bull Atom. Sci. 58:1 (2002)

Allison ‘How to Stop Nuclear Terror’ Foreign Affairs 83:1 (2004)

G. Bunn, Steinhausler and Zaitseva ‘Strengthening Nuclear Security Against Terrorists and Thieves Through Better Training’ The Nonprolif. Rev. (Fall-Winter 2001)

M. Bunn & Wier ‘The Seven Myths of Nuclear Terrorism’ Current History (April 2005)

Cameron ‘WMD Terrorism in the United States: The Threat and Possible Countermeasures’ The Nonprolif. Rev. (Spring 2000)

Falkenrath ‘Confronting Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Terrorism’ Survival 40:3 (1998)

Finlay & Grotto ‘The Race to Secure Russia’s Loose Nukes: Progress since 9/11’ (The Henry L. Stimson Center, Center for American Progress, 2005)

Frost ‘Nuclear Terrorism Post-9/11: Assessing the Risks’ Global Security 18:4 (2004)

Frost ‘Nuclear Terrorism After 9/11’ Adelphi Paper 45:378 (2005)

Hecker ‘Toward a Comprehensive Safeguards System: Keeping Fissile Materials Out of Terrorists’ Hands’ Ann. AAPSS 607 (2006)

Kamp ‘An Overrated Nightmare’ Bull. Atom. Sci. 52:4 (1996)

Maerli ‘Relearning the ABCs: Terrorists and «Weapons of Mass Destruction»’ The Nonproliferation Review (Summer 2000)

May ‘September 11 and the Need for International Nuclear Agreements’, in ‘Nuclear Issues in the Post-September 11 Era’ (Foundation pour la Recherche Stratégique, 2003)

Pluta & Zimmerman ‘Nuclear Terrorism: A Disheartening Dissent’ Survival 48:2 (2006)

Spector ‘The New Landscape of Nuclear Terrorism’ in Barletta (ed) ‘After 9/11: Preventing Mass-Destruction Terrorism and Weapons Proliferation’ Occasional Paper, Center for Nonproliferation Studies (Monterey Institute of International Studies, 2002)

Steinhausler ‘What It Takes to Become a Nuclear Terrorist’ Am. Beh. Sci. 46:6 (2003)

Comments like :

(1) “My guess is that those ´terrorism experts´who don´t believe that terrorists want nukes, selectively present evidence that building nukes is hard. In contrast, those ´technical experts´who think that building nukes isn´t so hard, tend to assume intent.” (Would they? Could they?, posted Tuesday May 6, 2008 under terrorism, nuclear weapons by James Acton.)

(2) “One possible objection to an interesting and worthwhile chart is that the issue of intent is not analytically distinct from capability – in other words, terrorists might conclude that building a nuclear weapon[s] is too expensive.” (#6 Jeffrey Lewis, May 6 [2008], 07:21 PM.)

(3) “The project [Ellingsen´s] which the questions refer to is a terrorist attempt to build a nuclear device (as opposed to steal a finished one. Also as opposed to a radiological dispersion device). But the different papers have different approaches and ask slightly different questions, hence making the exact interpretation of ´would´and ´could´more rigorous doesn´t work.” (#21 Simen Ellingsen, May 13 [2008], 09:03 AM.)

Comments (1)-(3), clearly, shows almost zero understanding of the HEU bomb ( as I brought up as #10 Anonymous, May 6 [2008], 11:52 PM), which in conjunction is a suicide bomb, and a very crude nuclear weapon, if the setup (gadget) gets supercritical, as well as comments (1)-(3) shows an overall ACADEMIC understanding of the World.

What count in reality more than a scatterplot of nuclear terrorism experts opinions of “Would they? Could they?” ? :

“NRDC Natural Resources Defense Council

Media Center

Press Release

Radiation Monitors Cannot Reliably Detect Highly Enriched Uranium at U.S. Ports and Border Crossings

America Remains Vulnerable to Terrorist Nuclear Smuggling Despite Spending Billions

Washington (March 25, 2008) — Nuclear security equipment at U.S. borders and ports is failing to reliably detect highly enriched uranium entering the country, meaning Americans are spending billions for machines that don´t reliably detect the most dangerous nuclear material, making it possible for terrorists to smuggle in the material needed to build a nuclear bomb in the United States, according to an article published today in the April issue of Scientific American entitled: ´Detecting Nuclear Smuggling.´(pages 98-104).

The authors, both from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) are: Thomas B. Cochran, Ph.D., senior scientist and Wade Green Chair for Nuclear Policy; and Matthew G. McKinzie, Ph.D., senior scientist in the nuclear program. In conjunction with the publication of the article, NRDC has filed a petition with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to establish a date after which it would stop licensing or authorizing the export of highly enriched uranium for civil purposes.

The principal findings in the article are:

– As demonstrated both in two field experiments and using computer calculations, portal radiation detectors now used at U.S. border crossings and ports of entry cannot reliably detect significant quantities of highly -enriched uranium; – The design and construction of a simple nuclear fission bomb with highly enriched uranium is shockingly simple; – Even advanced versions of passive radiation portal monitor technology now being considered offer no increase in detecting hidden highly enriched uranium, despite the enormous investment the United States is poised to make in them; – Given that the only significant impediment to terrorist use of a crude atom bomb made with highly enriched uranium is obtaining the material, the authors urge the federal government to securing now widespread and vulnerable sources of highly enriched uranium.

Twice since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, NRDC has assisted an ABC News investigative journalist unit led by reporter Brian Ross to ship secretly a soda can-sized cylinder of depleted uranium weighing 15 pounds from foreign ports into the U.S., mimicking the routes a terrorist might use to smuggle highly enriched uranium. NRDC´s slug of depleted uranium passed undetected through the network of radiation portal monitors now operating at U.S. border crossings and ports of entry. Had the slug been lightly shielded highly enriched uranium, it would have presented an even fainter signal to the radiation portal monitors, according to the authors´calculations. NRDC´s subsequent research on simple nuclear fission bombs showed that the risks from terrorist acquisition of highly enriched uranium are even higher than even the authors had first thought.

Based on these findings, NRDC scientists and policy experts are recommending that the federal government shift its priorities to focus foremost on the elimination of highly enriched uranium sources worldwide. In this regard, NRDC filed today a petition for rulemaking with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) requesting that NRC establish a date after it would no longer license the civil use of highly enriched uranium or authorize its export.

Click here to read the article in Scientific American, go to NRDC´s petition to the NRC (pdf), or read read more about the issue and ABC News´smuggling experiments in 2002 and 2003.”

(www.nrdc.org/media/2008/080325.asp)

Ask theses questions in everything you read;

Who says What to whom in Which Media and in What cause???

Any terror organization is supposed to treathen the society to get the needed power, but when a nation (which I don’t wanna name….) tells the truth the way that will gain them most……