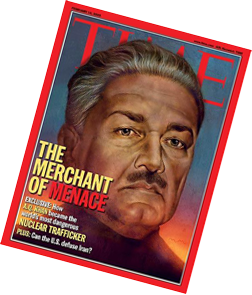

This magazine cover irritated

A.Q. Khan. Hey, it could have

been worse.

(A friendly warning: this is a long post.)

[Update | 2153. A few clarifications and elaborations have been added at the end. Look for the numbered notes sprinkled through the text.]

To observe something is to influence it, or so we are told. The ongoing Washington Post series based on papers written by A.Q. Khan in 2003 or 2004 (criticized recently by ISIS and here at ACW) certainly seems to be having an effect on the fortunes of the self-proclaimed father of the Pakistani nuclear bomb.

That’s because, according to Reuters and the New York Times, Khan has been talking too freely to foreign reporters for the liking of Pakistan’s government.

But here the story takes a twist.

There’s no reason to believe that A.Q. Khan has spoken with anyone from the Washington Post. In fact, it doesn’t appear that he’s been in contact with any members of the foreign media in recent months.1 What he has been doing is something much more dangerous: attacking the Pakistani military in a vain effort to rehabilitate his own good name. Perhaps thinking that Khan might win that battle in the court of public opinion, his antagonists apparently prefer to take him before another court — a literal court — in order to silence him, both for what he has said and for what he might say.

Bear with me and you’ll see.

The Official Line from the Government

The government of Pakistan is claiming that A.Q. Khan is jeopardizing national security, apparently through interviews with the foreign press. From the Reuters account:

“We basically seek permission to see Dr. (Abdul) Qadeer Khan and investigate into the matter as well as restrain him from making any statement and interacting with anybody,” government lawyer Naveed Inayat Malik told Reuters by telephone.

The petition was filed in the Lahore High Court after two articles in the Washington Post, published on March 10 and 14, reported that the Pakistani nuclear scientist had tried to help Iran and Iraq develop nuclear weapons, Malik said.

Those deals allegedly occurred with the knowledge of the Pakistani government. Both the Pakistan government and Khan have denied the reports.

And according to the Times:

A copy of the government petition obtained by The New York Times cited two articles published on March 10 and 14 by The Washington Post that “have national security implications for Pakistan as they contain allegations related to nuclear program and nuclear cooperation. Further they have likelihood of adversely affecting friendly ties with the government of Iran and Iraq.” The petition requested the court to direct Mr. Khan to “refrain from interacting with foreign media.”

But there’s just one little problem. Khan hasn’t been talking to the Washington Post. That much is clear from the stories themselves. The March 10, 2010 story (by Joby Warrick) was based not on interviews, but on documents found by UNSCOM in Iraq in the 1990s, first described by ISIS back in 2004. (The article was occasioned by the publication of David Albright’s new book, Peddling Peril.)2

And the March 14, 2010 story — the latest in the above-mentioned series by R. Jeffrey Smith and Joby Warrick — goes out of its way to tell us that Khan himself has not been involved:

Khan’s account and related documents were shared with The Post by former British journalist Simon Henderson, now a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. The Post had no direct contact with Khan, but it independently verified that he wrote the documents.

Pointing Fingers at Everyone Else

So what’s moved Islamabad to go to court? The answer is not completely clear, but it seems to be twofold: first, what Khan has said about the Post’s reporting in the Pakistani press, and second, what the Post series suggests that Khan might say next.

Let’s review.

The first story in the Post series, appearing on November 13, 2009, described what Khan had written about past dealings with China. But more importantly, it suggested that his motive for writing and leaking the papers was to make sure he would not take the fall alone:

[T]he narratives are particularly at odds with Pakistan’s official statements that he exported nuclear secrets as a rogue agent and implicated only former government officials who are no longer living. Instead, he repeatedly states that top politicians and military officers were immersed in the country’s foreign nuclear dealings.

Khan has complained to friends that his movements and contacts are being unjustly controlled by the government, whose bidding he did — providing a potential motive for his disclosures.

Overall, the narratives portray his deeds as a form of sustained, high-tech international horse-trading, in which Khan and a series of top generals successfully leveraged his access to Europe’s best centrifuge technology in the 1980s to obtain financial assistance or technical advice from foreign governments that wanted to advance their own efforts.

That certainly sounds nothing at all like Khan’s televised confession of February 20, 2004, in which he maintained that “there was never ever any kind of authorization for these activities by the government.”

Khan actually has been repudiating his televised confession since at least May 2008. Around July of that year, he had also accused exiled former military ruler Gen. Pervez Musharraf, the Army, the ISI (military intelligence), and the SPD (the branch of the Army in charge of nuclear security) of involvement in his proliferation activities. But after awhile, he had quieted down.

Now Khan was quick to confirm the Post’s story in an interview with the News of Pakistan. He also returned to his old form, taking aim at Musharraf, who (so Khan claimed) conspired against Khan with CIA director George Tenet:

Dr Khan questioned what type of justice it was that the truth was made secret for countrymen while it was transferred to the US. The nation must know that national secrets were handed over to Washington by the former president who was an American stooge, he said. He said the nation knew well who its well-wisher was.

[snip]

Khan demanded inquiry and trial against Musharraf and his coterie. It is an open secret that Musharraf had deep-rooted contacts with Israel and God knows how many secrets he had transferred to them. He said under a planned policy the former president had transferred all responsibility over his shoulders, which he was not going to deny. But, he demanded to expose his confessional statement secured under duress or to record his statement afresh so that real facts might be revealed.

(The Post briefly took note of this item at the time.)

But even before Khan’s interview appeared in the News, the same paper had reported that he was under investigation on suspicion of having spoken with the Post.

A Turn for the Worse

Probably his interview with the News did not help his cause, but it was the next story in the Post, on December 28, 2009, that may have sealed Khan’s fate. In mid-January 2010, the News reported on a meeting of senior military and civilian officials with the purpose of dealing with the Khan matter:

The enormity of official concerns is evident from the fact that a high-level meeting on Friday, presided over by no less than Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani, was held to exclusively discuss the issue of Dr Khan’s unrestricted exchanges.

The meeting was attended by top military brass and government’s legal eagles. The meeting was reportedly convened at the request of the security establishment and was attended by Interior Minister Rehman Malik, Minister Babar Awan, PM’s Adviser Latif Khosa, Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee Gen Tariq Majid, DG ISI Lt Gen Shuja Pasha, DG Strategic Planning Division Lt Gen (retd) Khalid Kidwai, Attorney General Anwar Mansoor.

What was it about the second Post story that did it — if that’s really what did it? We can’t be sure, but I’d point to this passage:

Contradicting Pakistani statements that the government had no involvement in such sensitive transfers, Khan says his assistance was approved by top political and Army officials, including then-Lt. Gen. Khalid Kidwai, who currently oversees Pakistan’s atomic arsenal.

The document in question was apparently written sometime in late 2003 or early 2004, during the official investigation into Khan’s activities. But in late 2009, it would have suggested where Khan might be prepared to go next.

Despite his plea that he had not spoken with the foreign media, Khan was returned to house arrest in late January.

[edited for clarity] Now, the appearance of retired Lt. Gen. Kidwai’s name in the Post must have brought some people in Islamabad up short. For comparison, see the Sunday Times article by Simon Henderson that first brought Khan’s papers to light. The only names it named were those of the deceased (brackets original):

On Iran, the letter says: “Probably with the blessings of BB [Benazir Bhutto, who became prime minister in 1988] and [a now-retired general]… General Imtiaz [Benazir’s defence adviser, now dead] asked… me to give a set of drawings and some components to the Iranians…The names and addresses of suppliers were also given to the Iranians.”

On North Korea: “[A now-retired general] took $3million through me from the N. Koreans and asked me to give some drawings and machines.”

(Of course, it also must have helped that Khan refused to comment on that article.)

Everyone named in the November 14, 2009 Post story is also deceased, so the appearance of the name of a living individual was new.

Bearing all this background in mind, the latest development appears to be driven by the account from the Khan papers given in the March 14, 2010 Post story. It named two more living retired senior Pakistani military officials, Admiral Sirohey and General Beg, as playing opposed roles in dealings with the Iranians.3

And now, in a novel twist, Khan himself has been wheeled out to deny the latest report.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Left aside so far: whether anything Khan writes or says is true.

Most analysts of non-proliferation have long doubted his original, televised confession. But there is also reason to doubt that Khan acted on orders from the top. (The case for Khan as an independent operator has been made in detail by Christopher Clary.)

Between these poles is another possibility. Let’s call it the coalition of the corrupt. One could imagine that, in a sufficiently “loose” and “open” setting, where the military is largely unaccountable to civilian authority, a weapons scientist on the make could form alliances of convenience with military men, who — from the perspective of foreign customers — would act as gatekeepers to the advanced technology.

That doesn’t mean that Khan is telling the truth. It’s possible he acted without any “top cover.” It’s also possible that he had “top cover,” but decided for reasons of his own to accuse innocent individuals. There’s no way for us to know. But we can envision his situation in late 2003 and early 2004, during the investigation by Pakistani intelligence. If Khan had partners in crime, and if he thought they were about to sell him out, why then, he’d sell them out, too. Thus the documents, which he wrote and sent out of the country for safekeeping. What an irony it would be if they now come back around to cost him his freedom — but nothing, perhaps, that game theory wouldn’t predict.

Postscript: This story isn’t over; in a comment at ACW, R. Jeffrey Smith of the Washington Post wrote that “the final thread [is] not yet reported.”

Update | 2153.

1 Simon Henderson, who is not affiliated with the Post, points out that he’s named in the Pakistani press as a suspected Khan contact (see the News and Daily Times).

2 What’s more, the March 10 Washington Post story is not entirely new. The Post covered the Iraq documents on February 5, 2004 (Joby Warrick, “Alleged Nuclear Offer to Iraq Is Revisited; Memos Indicate Attempt to Sell Pakistani Bomb Plans, Equipment on Eve of ’91 War”), albeit not at the same level of detail as earlier this month. Unfortunately, the story does not appear online.

3 As it happens, the March 14 Washington Post story is not entirely new, either. The Post covered Khan’s interactions with Iran, albeit without the benefit of his written statement, on January 24, 2004. Gen. Beg was named. Here’s the notable passage:

Chaudry Nisar Ali Khan, a former cabinet-level assistant to Nawaz Sharif, the prime minister at the time, said in an interview Thursday that Beg approached him in 1991 with a proposal to sell nuclear technology to Iran. Former U.S. ambassador Robert Oakley said Beg told him in 1991 that he had reached an understanding with the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards to help Iran with its nuclear program in return for conventional weapons and oil.

Also, a different and probably better explanation for the latest court action than what I suggested above appeared in Tuesday’s New York Times:

The [government’s] petition was filed on Monday, hours before a court in Lahore was to announce a verdict on Mr. Khan’s petition to have his travel restrictions relaxed.

In other words, the new action seems to have been designed to prevent, or at least delay, any legal escape from confinement that Khan might otherwise manage. The March 10 and 14 articles in the Post look like a handy pretext more than a source of genuine alarm. The real damage was already done back in late 2009.

Josh:

Pakistan seeks a civil nuclear deal similar to the one India received. There is a high-level Pakistani delegation in DC. A new court action is sought against AQ Khan.

Joshua Pollack writes: “In fact, it doesn’t appear that [A Q Khan has] been in contact with any members of the foreign media in recent months.” That might be true but it seems that the Pakistan government regards me as a journalist and thinks he has been in contact with me.

Although the Reuters and New York Times stories don’t mention me, I get a mention in the reports of yesterday’s hearing in the Lahore High Court in two local Pakistani newspapers today: The News and the Daily Times.

The latter makes clear that it is the government lawyer who is refering to me. I haven’t seen the second government petition, filed yesterday, but the first, written by the deputy attorney general of Pakistan and filed on January 18, identifies me in similar terms.

Simon Henderson

And the articles, citing the government’s lawyer, describe you in such warm and friendly terms, too. (Interesting that it comes out the same way in both articles. You can practically hear the spittle flying. Did he put that double epithet in the legal brief? It’s like a bad day on C-SPAN.) Thanks for pointing that out.

It would be unreasonable to imagine that what the Washington Post chooses to publish is somehow in your hands, even if you originally provided them with the documents. Do you mean to suggest that the Pakistani authorities suspect something more than that?

Whether AQK has done it on orders or not – he is the biggest nuke trafficker. He was not obliged to follow anybody’s orders since he was the boss in his own field. He kept letters all over the world to safeguard himself from some eventuality displays that he knew what he was doing was terribly wrong. Why did he not go to press that time?

But why would he? A Q Khan, Bashir‑ud‑Din Mahmood and the likes in Pakistan will not hesitate to proliferate to the Muslim brethren at the slightest religious stimulus. Pakistani universities teach subjects like nuclear electronics, metallurgy etc with great emphasis on practical learning. It is surprising to note that even small universities like Allama Iqbal Open University of AzaKhel has a department of Nuclear Sciences along with Department of Hadith and Seerah and Department of Islamic Thought, Islamic Law and Jurisprudence. The students in such Universities are generally from lower middle class who are imbibed with such great religious hatred towards India as if it runs in their genes.

And now the US assistance to Pakistan for more nukes. Just imagine what Pakistan will do with extra uranium or plutonium? If they are someway allowed to purchase through a proper deal with IAEA monitoring clearly means that the homegrown production which is unaccounted for by any standards is EXTRA. They will certainly proliferate. Now that they have extra nukes – the entire nukes will be shipped and not just written papers and diagrams.

Two thoughts on that.

1) I do not think AQ Khan is in fact any kind of Islamist, despite some public remarks in this vein. Remember, North Korea was a customer. Their money’s just as green as anybody’s.

He also just don’t have the vibe, if you’ll pardon the expression. Speaking for a moment as a Person of Whisker, I just don’t see Dr. Khan as a bearded fanatic.

2) The Pakistanis can ask for whatever they want in the Strategic Dialogue. I don’t know a single well-informed person who imagines that the U.S. would ever agree to pursue an India-style civil nuclear deal with Pakistan. It’s simply not in the cards. I sincerely hope no one is allowing anyone in Pakistan to mislead themselves on this score.

A clarification on the status of general Kidwai: he is now indeed a retired general, but still very much formally in charge of Pakistan’s nuclear military complex. This was not clear from reading the post.

You’re right. My attempt to clarify only added confusion. I’ll fix that.

Apparently the movement restrictions are now mostly lifted, though the ban on press contacts remains:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/30/world/asia/30pstan.html?hp