If the paucity of North Korean Nodong MRBM tests prior to deployment doesn’t mean that it’s secretly an old Soviet weapon not seen previously, what does it mean?

There are other explanations for a limited testing regime that don’t seem like quite so much of a reach.

First, let’s consider that the North Koreans had been working on ballistic missiles for some time already. North Korea’s missile program started in the mid-1960s, and benefited from cooperation with the Chinese starting in the early 1970s. So there was a base to build from.

Second, the missile wasn’t made from scratch and didn’t involve cutting-edge technology. The Nodong relies on technologies associated with the Scud-B, which had been in North Korean hands from as early as 1972. If we can accept that North Koreans were already experienced at making Scud-Bs by the mid-to-late 1980s, when they were reportedly helping the Iranians set up their own production lines, then the Nodong appears to be a reasonable progression from their known capabilities at the time.

Third, North Korea’s missileers simply may not require that many tests before considering a weapon operational.

Fourth, we may be mis-counting the tests. It’s possible to miss some sorts of events, especially if you aren’t already looking for them very closely.

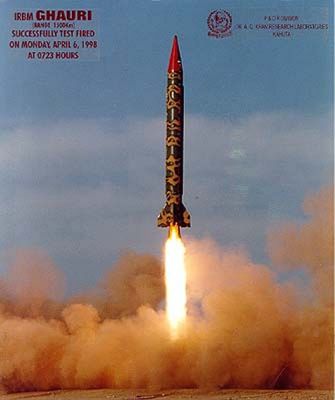

Also, following from Geoff Forden’s idea of consortium development, early tests of the Nodong in Pakistan and Iran could also be considered part of the part of the development effort. (Iran’s first Nodong flight-test, in 1998, reportedly blew up about 100 seconds after launch.)

Actually, the consortium idea is not so new. In describing its research methodology, the Rumsfeld Commission alluded to it in its 1998 report:

We examined the ways in which the programs of emerging ballistic missile powers compared with one another. For example, we traced the development histories of the related programs of North Korea, Iran, Iraq and Pakistan and the relationships among them. This comparison helped in identifying the similarities between programs, the extent to which each had aided one another in overcoming critical development hurdles and, importantly, the pace at which a determined country can progress in its program development.

All of these points add up to an explanation that seems more reasonable than an elusive gang of border-jumping Russians with phantom missiles from the past.

Come to think of it, though, that would make a great Terry Gilliam movie.

Tomorrow: What has the U.S. Intelligence Community said about North Korea’s missile production capabilities?

Yesterday: What Is North Korea Capable Of?

Please consider what makes more sense to you all:

Missing at least several dozen test launches (of the Scud-B alone, but also of the Scud-C and of course the Nodong-A!) by North Korea in the 1986-1998 timeframe plus north-korean super-duper-engineers (single-handedly outclassing everybody elses rocket-scientists by reproducing a complete production-line, not only for a perfect clone of the Scud-B-missile itself, but also the belonging 9P117M1-TELs etc., from only a very limited number of missiles with at best sketchy documentation acquired through an intermediary) with ultra-technology obviating the need for extensive flight testing at their hands – and all this already 20-30 years ago (that sounds quite “Dr. No”/“You only live twice” or rather science-fiction- or maybe even fantasy-genre to me…);

or:

An only limited understanding and incomplete intelligence data of the soviet missile program in the 50ies/60ies (i think this is self-evident if you look e.g. at the, particularly considering the SLBM-program, rather limited and contradictory information in the CIA “intelligence handbook on soviet guided missiles” from 1969 – see CIA FOIA-document SR IH 69-2), which leads to a misinterpretation of the DPRK’s Nodong-A as “completely indigenous reverse-engineering-enhancement activity”, not revival of an old, obsolete and thus obtainable soviet R-17-predecessor (the R-15) with help from russian Makeyev-personnel (who were initially responsible for that project – and also the R-17/SS-1c/Scud-B and the 9M77/SS-1d/Scud-C);

BTW, the “consortium development” idea does neither explain the alleged 100% success rate of the pakistani Ghauri after only one successful north-korean shot (and that one not even to full range!) nor the trouble-free deployment of iranian Scuds procured from the DPRK during Gulf War I…

Oh, and statements from “one north-korean defector” (aka a single source of questionable dependability – never forget the possibility of a deliberate deception-effort by the opposite side!) can’t be earnestly called a secure source of information considering the 1972-number (my guess is that something in the 1980-1986 timeframe is more realistic – especially if we consider the possibility of iranian financing of the Scud-procurement effort).

It turns out that the R-15 engine was a 5 chamber design and thus had no relation to the R-17 or NoDong. Are we now allowed to hold a funeral for the idea that the NoDong-A is the R-15?

As far as the rest, we don’t know what the DPRK’s test standards are and if they’re reverse engineering a proven design their issues of confidence are with their machining and material science not with the fundamentals soundness of their design thus negating the need for extensive re-certification flight test regime of the scud.

In the case of the 1972 transfer, yes, one defector’s account is only that. Which is why I wrote “as early as.” There are many defectors who have spoken of Scud-B transfers. They collectively give a range of dates from 1972 to 1981 or so.

But actually, I wouldn’t be so surprised if North Korea got not just some Scud-Bs but an entire factory sometime in that timeframe. Why not? North Korea was producing its own Scud-Bs after a certain point, and there’s no reason to assume they achieved that ability wholly on their own, prideful claims notwithstanding. To the contrary.

Unlike the Nodong, after all, the Scud-B is known to have existed previously. For me, at least, that makes a difference.

As for the Nodong, I can swallow the idea of missing some tests a little more readily than the idea of missing an entire missile for decades.

At bottom, this entire debate has to do with which unobserved events are less unlikely. Perhaps it just comes down to a matter of taste.

Josh,

I think there’s another possibility to add to your list for consideration: North Korea’s MRBM program is really a political program designed to satisfy internal and/or external political objectives.

Azr@el:

Do you have any credible evidence supporting your claim? (BTW, you can read a lot of horseplay on the ‘net – like the Scud-B using UDMH as propellant or the Guideline-SAM being solid-fueled-only…)

If yes – put your cards on the table!

Otherwise don’t try to bluff to make your position seem more likely!

Jochen, I believe you will find the discussion in this thread…

http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/2404/what-is-north-korea-capable-of#comment

…beyond sufficient. It also makes my position more likely; where my position consist of your position being highly unlikely. As to the allegation of me bluffing…hmmm…I feel it’s best I dismiss it as an emotional outburst.