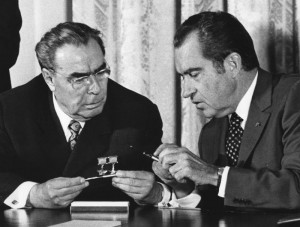

The Nixon administration needed to make many adjustments in order to prepare for strategic arms limitation talks with the Kremlin. One change was in the terminology used to describe how US nuclear forces were supposed to stack up against the Soviet Union.

Prior to the SALT negotiations, US Presidents and Congressional leaders lined up squarely behind the objective of strategic superiority over the Soviet Union. (One of the arguments used by the Kennedy administration to secure the Senate’s consent to ratify the Limited Test Ban Treaty was that it reinforced US strategic superiority.) Even as the Kremlin played catch up – especially when the Kremlin played catch up — advantage was presumed to matter. Senator Richard Russell (D – Georgia), a formidable presence on the Armed Services and Appropriations Committees, did not mince words on this subject. His classic quote:

If we have to start over again with another Adam and Eve, I want them to be Americans; and I want them on this continent and not in Europe.

The Nixon administration was in a quandary. The Kremlin was not about to accept or acknowledge American strategic superiority in the SALT negotiations, even if Washington enjoyed qualitative advantages in all three legs of the Triad. At the same time, SALT skeptics were going to be up in arms if the administration backtracked from the goal of strategic superiority. What to do?

The Nixon administration’s answer to mollify hawks while pursuing accords with the Kremlin was “strategic sufficiency.” The key elements of strategic sufficiency were worked out in internal deliberations and spelled out in a June 17, 1969 memo to Henry Kissinger written by Laurence Lynn and Helmut Sonnenfeldt for an NSC meeting the next day. These criteria were codified in National Security Decision Memorandum 16, circulated a week later. Here they are:

The Nixon administration’s answer to mollify hawks while pursuing accords with the Kremlin was “strategic sufficiency.” The key elements of strategic sufficiency were worked out in internal deliberations and spelled out in a June 17, 1969 memo to Henry Kissinger written by Laurence Lynn and Helmut Sonnenfeldt for an NSC meeting the next day. These criteria were codified in National Security Decision Memorandum 16, circulated a week later. Here they are:

1. Maintain high confidence that our second strike capability is sufficient to deter an all-out surprise attack on our strategic forces.

2. Maintain forces to insure that the Soviet Union would have no incentive to strike the United States first in a crisis.

3. Maintain the capability to deny the Soviet Union the ability to cause significantly more deaths and industrial damage in the United States in a nuclear war than they themselves would suffer.

4. Deploy defenses that limit damage from small attacks or accidental launches to a low level.

The sufficiency standard was no barrier to strategic modernization programs, especially after the Kremlin resolved to counter US qualitative advantages with a quantitative build-up in land- and sea-based missiles, silos and submarines. Defenders and critics of the SALT accords were unhappy, and let the Nixon administration know it. When asked to explain what sufficiency actually meant, Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard responded with another keeper quote:

It means that it’s a good word to use in a speech. Beyond that, it doesn’t mean a God-damned thing.

Just finished reading Terry Terriff’s “The Nixon Administration and the Making of U.S. Nuclear Strategy,” which emphasizes the delay between the coining of the phrase “strategic sufficiency” and the actual strategic and doctrinal changes it was meant to represent. The whole thing is an interesting example of how the political, the bureaucratic, and the strategic interact to produce new policy.