The only top-of-the-charts space-age instrumental was silenced by the highest yield US atmospheric test ever conducted.

OK, I’m taking literary license.

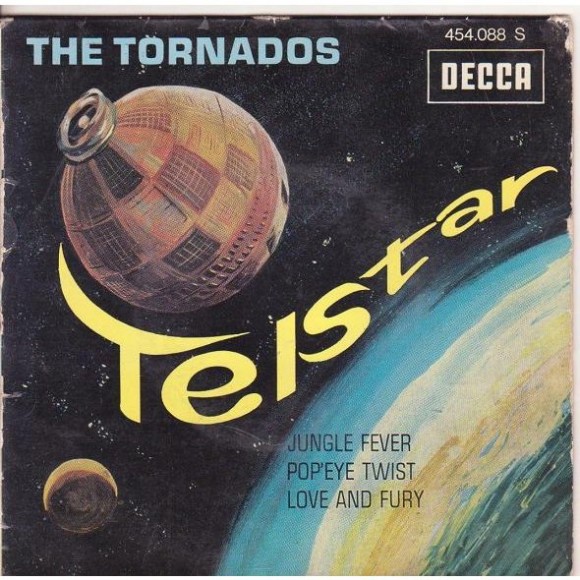

Readers of a certain age will recall Telstar, the satellite and the top-40 single. Telstar enabled the transmission of images across the Atlantic on our black-and-white TV screens, just as the British music invasion of the US airwaves was building. Before the Beatles scored their first number-one hit and transfixed us on the Ed Sullivan Show, another British band, The Tornados, topped the US charts with Telstar, a tune inspired by the satellite. Telstar was one of the satellites victimized by Starfish Prime, the 1.45-megaton whopper detonated 248 miles above the Pacific. Telstar was dying from nuclear effects while it was #1 on the Hit Parade.

Want to know more about the intersection of national security and space, as viewed through the prism of the US-Soviet competition? Try Clay Moltz’s The Politics of Space Security (2008). [Another disclaimer: my last book and this one share the same publisher.] One peripheral episode in Clay’s book might explain how Telstar and Starfish Prime helped to tip the scales toward the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

In 1962, President Kennedy was being whipsawed by conflicting pressures over atmospheric tests. His gut – and growing public sentiment angered by fallout – told him to negotiate a test ban. What’s more, JFK’s science advisors were telling him that continued testing could place the health of astronauts at risk. But Kennedy was also under intense pressure to resume atmospheric detonations after the Kremlin broke a 34-month-long moratorium and began a cascade of tests in September 1961. The United States followed suit, and missile defense advocates were particularly keen to learn more about the effects of high-yield atmospheric detonations. They got their wish on July 9, 1962, when a Thor missile was launched from Johnston Island carrying a W-49 warhead.

Here’s Clay’s account of the percussive effects of Starfish Prime:

The blast disrupted radio transmissions as far away as California and Australia for several hours. As Atomic Energy Commissioner Glenn Seaborg noted in his memoirs, ‘To our great surprise and dismay, it developed that STARFISH added significantly to the electrons in the Van Allen belts. This result contravened all our predictions.’ The test proved embarrassing and costly, particularly as British and U.S. scientists had cautioned against its likely effects. The EMP radiation it generated eventually disabled at least six satellites, including the British Ariel I, the U.S. Traac, Transit 4B, Injun I, Telstar I, and the Soviet Kosmos 5.”

US atmospheric testing continued after Starfish Prime, but not for long. Many risks were clarified by this test: risks to public health and to astronauts, who were far bigger rock stars than the Tornados; risks to satellites, communication links, and command and control, as well as the risks of relying on missile defenses in the event of nuclear exchanges. Clay writes that Starfish Prime helped convince JFK that his gut was right and that a test ban treaty was needed.

The modern-day equivalent of Starfish Prime was the PLA’s kinetic energy anti-satellite test on January 11, 2007. This test, carried out at twice the altitude of Starfish Prime, had appalling debris consequences, increasing the collision risk to approximately 700 satellites in low earth orbit, according to the US Air Force Space Command. The test produced over 2,000 pieces of debris large enough to be catalogued and tracked by the US Space Surveillance Network and over 35,000 smaller debris fragments. Space objects and manned space operations will have to dodge this debris for decades.

Why did China create such a mess in space? We don’t know for sure because Beijing still operates on the presumption that transparency can reflect weakness, while opaqueness can increase strength. We do not know, for example, whether China’s leaders were warned of, as President Kennedy was, or had the presence of mind to inquire about the dangers to manned spaceflight that could result from testing.

My guess is that the reasons for China’s KE-ASAT test may not be very different from those reflected in Starfish Prime: anxieties over national security, deference to excessive military testing requirements, and an inability to envision just how messy the test consequences would actually be.

Can significant good result from China’s irresponsible KE-ASAT test? Some positives are already apparent. Recognition of the space debris problem has now extended beyond experts to national leaders. Another glaring problem, the absence of space traffic management mechanisms, is starting to be addressed. The US Strategic Command’s Joint Space Operations Center has stepped up to the plate by voluntarily issuing potential collision or conjunction warnings – including 400 notices to Russia and China over the past year. In other words, the United States is now reminding China on a regular basis of the potentially catastrophic consequences of conducting a high-altitude KE-ASAT test.

Growing sensitivity to threats to the global commons of space and provisional steps to manage the debris problem is insufficient. China’s KE-ASAT test, like Starfish Prime five decades ago, warrants more structured and far-reaching protective measures. The modern-day analog to the Limited Test Ban Treaty is a Code of Conduct for responsible space-faring nations that addresses debris and traffic management imperatives. If China blocks its creation, its leaders will have not learned nearly enough from their KE-ASAT test.

Note to readers:

A slightly different version of this essay appeared in Space News.

MK

If I recall right, the US also carried out a ASAT test soon after the Chinese using our missile defense ships, though minus the debris problem since it was much lower down. As I see it, electrons from STARFISH were not the biggest problem (exploding nuclear weapons in space was!), debris was not the biggest problem from the Chinese test: the perpetuation of ASAT testing was. What I am saying is that even if there is a nice clean debris-free way to kill satellites, probably this is not a great idea.

USA 193. Pretty clearly a tit-for-tat response to show the Chinese that we have similar capabilities:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/wikileaks/8299491/WikiLeaks-US-vs-China-in-battle-of-the-anti-satellite-space-weapons.html

I agree that while the debris problem is a significant issue, the Code of Conduct for responsible spacefaring nations that MK mentions is needed for many more reasons than just this immediate effect. This kind of space arms race will have plenty of other negative consequences even if the debris problem could be miraculously negated.

The many thousands of people killed by JDAMs and other satellite-guided weapons might disagree with that assessment. When, some time in the future, the next target of such finds himself with the means to cobble together an ASAT capability, I’d be hard-pressed to explain to him why he ought to lay down and die to preserve the peaceful sanctity of the heavens.

There were no shortage of people in 1914 who thought that shooting down airplanes was not a great idea, but then as now, it’s too late for that. There are limits we can hope to maintain, but “no killing satellites” isn’t one of them.

> What I am saying is that even if there is a nice clean debris-free way to kill satellites, probably this is not a great idea.

I’m going to agree with John Schilling here:

>> I’d be hard-pressed to explain to him why he ought to lay down and die to preserve the peaceful sanctity of the heavens.

Folks, the heavens are already heavily militarized. If it comes down to a conflict between a power that makes major use of space for direct military advantage (as an American, I decline to specify who that might be) and a power that has some sort of counter-space/ASAT capability, I’d guess the ASAT power would use the capability. Considerations of down-stream consequences such as space messiness might not carry the day against more urgent considerations.

First of all, you can’t just “cobble together” an ASAT capability, particularly anything that could take out GPS (for JDAMs). Developing ASAT weapons is not especially technically difficult for nations that already have space launch and spacecraft development and production capabilities, but such capabilities are also not notably less demanding than the production of nuclear weapons. Ergo, every nation which does or might in the future possess ASAT weapons is also an actual or potential nuclear weapons power. In reality, the short list of potential space weapon threats to U.S. satellites is identical with the short list of nuclear threats.

So these are not people we will be targeting with JDAMs, except in one scenario: nuclear war, or in any case war (at the strategic level) with another nuclear power, which in practice is likely to be (or become) the same thing.

Ah, yes, I remember Telstar well:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u2ybCjf6ras

But then I remember Sputnik I pretty well too.

A nit: the highest yield US atmospheric test was Castle Bravo, at 15MT about 10 times the yield of Starfish Prime. It’s also not the highest altitude US test (Argus III, 540km). Perhaps you meant the highest yield US exoatmospheric test?

thanks, Otto–

MK

It’ll probably take another 40 years for China to catch up to the US in creating the total amount of space debris up to this time and another 40 years to creating the same amount per capita. But by then, the US would have created more space junk because it would be compelled not to lose in any battle. Just looking at the ASAT test the US carried out reflects that thinking.

Satellite collisions like the Iridium Cosmos crash cause as much debris as high altitude ASAT tests btw.

That will likely happen before the next ASAT incident.

Bigger worry.

Well, the good thing is that there is a negative feed back mechanism to suppress the production of debris. Nations that are capable enough to produce space debris know that it is a mutually destructive thing to create space debris.

How many ASAT events does it take to make space practically unusable? If that were to happen, how many years would it take for the debris to come down? I guess that they won’t form a ring many million years later, right? That would be a ghastly monument for the victory of our urges against reason.

Ahuh,

Where did you gather your statistics? China currently has a much larger debris population than the U.S. To quote Megan Ansdell:

“Three countries in particular are responsible for roughly 95 percent of the fragmentation debris currently

in Earth’s orbit: China (42 percent), the United States(27.5 percent), and Russia (25.5 percent) (NASA 2008, 3).”

Her work can be found at http://www.princeton.edu/jpia/past-issues-1/2010/Space-Debris-Removal.pdf.

Brian Rubaie

This from an oped by Darren McKnight and Molly Macauley (“Space Debris: What are we Waiting For?”) in the November 28 issue of Space News:

“Recent analysis shows that regions in low Earth orbit have officially exceeded the critical population density whereby on-orbit collisions will create more debris than can be cleansed by atmospheric drag. Once this point is reached, the debris population will grow exponentially even without new launches.”

It has been accepted for some time that the debris population at some altitudes in LEO is above critical.

It needs to be understood, however, that the time scale for this exponential growth is decades.

So it is already happening, but relatively slowly.